A hallmark of the black nationalism movement in the 1960s was the idea of African-Americans patronizing African-American businesses.

This approach with its pull-ourselves-up-by-the-bootstraps subtext has been a prominent tenet for many African-American leaders ever since. But its roots go far back, nearly to the time of the Civil War.

Indeed, in the early 20th century, it was already well-established as a long-sought goal in the black community, and, in Chicago, Jesse Binga, the city’s first black banker and perhaps the most powerful in the nation, was a key proponent.

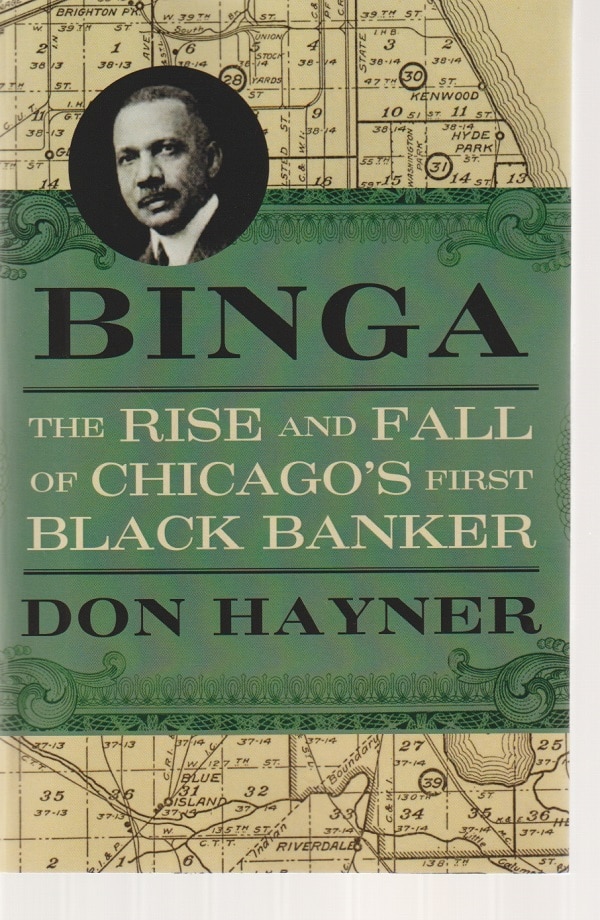

The goal, as Don Hayner relates in his well-researched, expansive biography Binga: The Rise and Fall of Chicago’s First Black Banker [Northwestern University Press, 312 pages, $24.95], was to make the Black Belt somewhat self-sustaining. It would never be possible to totally sever African-American spending from the mainstream white economy — and probably a bad idea. But the more that black dollars circulated within the black community, the stronger would be the economic strength of African-Americans.

Binga worked with other leaders, such as his business ally Robert S. Abbott, the editor-publisher of the Chicago Defender, and Julius Taylor, the editor-publisher of another black newspaper, the Broad Ax, as well as kingpins in the African-American criminal underworld, to encourage what they called “Double Duty Dollars.” This was money spent by blacks to buy goods or services from black-owned enterprises.

It was a way to “advance the race,” notes Hayner, who adds:

“Black capitalism was powered by Double Duty Dollars and inspired by practical mantras like ‘Don’t spend where you don’t work.’ Of course, Binga said the banks should lead: ‘I would say to those aspiring to be of influence in our community, to remember that the banks and business men are the bulwark of the community.’ ”

“Self-assertive Negro”

In the early decades of the 20th century, Chicago’s South Side was proud of Jesse Binga, and so too were prominent blacks in the nation. Indeed, Binga, who was born in Detroit in the final months of the Civil War, was one of the few subjects on which conservative Booker T. Washington and firebrand W.E.B. DuBois saw eye to eye.

In the early decades of the 20th century, Chicago’s South Side was proud of Jesse Binga, and so too were prominent blacks in the nation. Indeed, Binga, who was born in Detroit in the final months of the Civil War, was one of the few subjects on which conservative Booker T. Washington and firebrand W.E.B. DuBois saw eye to eye.

Washington hailed the Chicagoan as the most successful black banker and real estate dealer in the nation. DuBois went even further, asserting:

“[Binga] was outspoken; he was self-assertive; he could not be bluffed or frightened…he did not bend his neck nor kow-tow when he spoke to white men or about them; he represented the self-assertive Negro, and was even at times rough and dictatorial.”

“Unbowed and outspoken”

Despite the great respect accorded Binga as a business leader, he and his wife Eudora were never accepted as part of black South Side’s upper-crust, perhaps because Eudora was the sister of the hugely successful John V. “Mushmouth” Johnson, king of South Side policy gambling (an early form of today’s lottery).

Nonetheless, each day, Binga crosses paths with the high and the low of the Black Belt, including sometime business associate Oscar De Priest, the first African-American to be elected to Congress since Reconstruction; cosmetics manufacturer Anthony Overton; pioneering aviatrix Bessie Coleman; anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells; Dan Jackson, “the czar of the colored underworld;” Chicago’s first black librarian Vivian Harsh; Father Augustine Tolton, the first black priest in the nation; and social worker Ada S. McKinley.

They are important figures in Hayner’s Binga because this is not just a biography of a prominent business leader but also a look at the African-American South Side of a century ago.

Binga is a book that makes clear that, for better and worse, the banker-real estate dealer was his own man. He wasn’t liked by all blacks, but he was widely respected within the African-American community, as Hayner writes:

“Even though some blacks despised Binga for being cold and arrogant, many also saw him as a ‘race man,’ unbowed and outspoken on behalf of blacks.”

To most whites, though, Jesse Binga was “an agent of doom.”

“Most hated”

That, in fact, is central to Hayner’s story of Binga’s life — how he helped blacks and, in the process, hurt and enraged whites.

Backed by his bank, real estate dealer Binga aggressively worked to lead “an exodus of black families out of the cramped, crowded, and contaminated housing in the Black Belt” — and into white neighborhoods

In the process, he became “the most hated man in Chicago — at least in white Chicago.”

In this era, the mental maps of Chicagoans, as well as many legal deeds, included sharply drawn lines indicating where whites were permitted to live and where blacks could live. At one point, some South Side whites put this into physical being by stringing a rope to create a boundary line at 27th Street and Wentworth with an attached sign that read:

“Negroes Not Allowed to Cross this Dead Line.”

What came next

Binga’s practices were such that one former employee told Hayner that the banker “was one of the original blockbusters.”

Hayner, though, disagrees.

Anyone who watched racial change in Chicago neighborhoods during the first 60 years of the past century saw horrificly damaging panic-peddling tactics that enflamed white antipathy toward blacks while also causing white flight, a term that fails to describe the deep grief at leaving behind family and community history as well as much of the value of years of investment.

Binga, “a steely-eyed realist and a proudly unapologetic capitalist,” didn’t employ such bitterly divisive tactics, Hayner writes:

“He simply moved black families in, and then whites moved out…He surely knew that white flight would often be the result, but if whites moved out, that was their business. Binga did, however, spike rents and push sale prices higher, in much the same way that many other real estate agents did.”

African-Americans who moved into those apartments formerly occupied by whites complained that Binga boosted their rents by as much as 50 percent.

Whites, though, were filled with fury at him, going so far as to blame him for the 1919 races riots in which more than three dozen whites and blacks were killed. A handwritten letter from “Headquarters of the White Hands,” delivered a few days after the riots to Binga’s home, told him,

“You are the one who helped cause this riot by encouraging Negroes to move into good white neighborhoods….You know what comes next.”

What came next was a series of at least eight bombings at the banker’s home and office over the next two years.

Business tragedy

Binga survived the bombings. Later, though, his bank and his real estate business fell victim to the Depression.

His bank was closed by state regulators in 1930, and, in 1933, he was convicted of embezzlement for highly questionable actions, perhaps taken in desperation to save his bank and business. He spent nearly three years in prison.

His was one of myriad business tragedies in the nation in those years, but, when Jesse Binga was riding high, he was one of the most respected persons on the black South Side.

And with good reason.

Patrick T. Reardon

2.19.20

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 12.2.19.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.