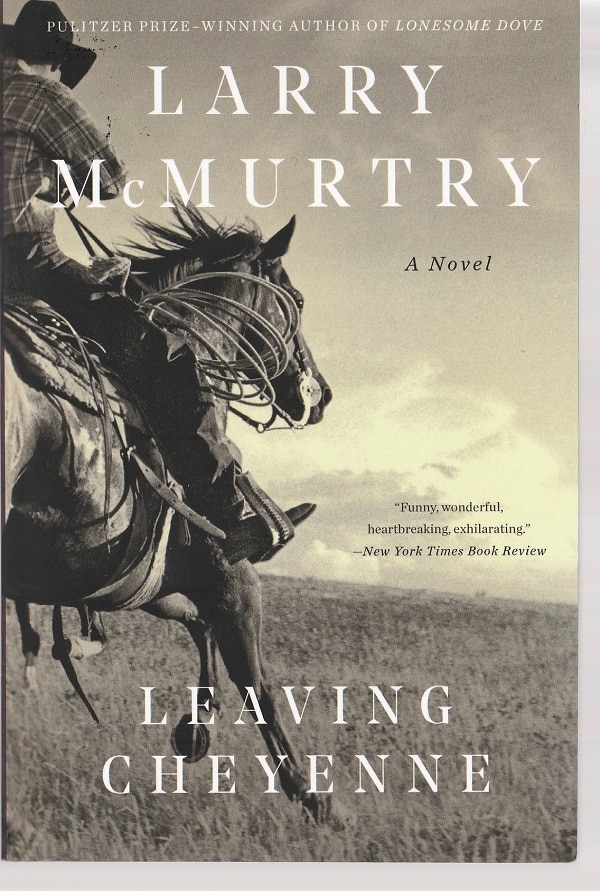

I’m not sure what to say. Larry McMurtry was a highly praised, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, and Leaving Cheyenne, his second book, has been described by some fans as his best.

But I found it flat. The fault may lie in me. Still, let me explain.

Leaving Cheyenne, set in rural north Texas, follows the lives of three friends and lovers over the arc of their entire lives, spanning much of the 20th century:

- Gideon Fry, the conscience-burdened rancher who reaps wealth from a lifetime of a strict, enjoyable work ethic.

- Johnny McCloud, the free-spirit cowboy who can fancy work but also leave it be, and who spends 38 years working side by side with Gid at his ever-larger ranch.

- Molly Taylor, the woman whom both men love and who loves both of them but who marries a man she doesn’t love.

Odd triangle

As literary love triangles go, this is an odd one inasmuch as there is very little jealousy between Gid and Johnny over Molly. Each spends many nights and sometimes afternoons in bed with her. Indeed, Molly’s first son Jimmy is Gid’s. Her second son Joe is Johnny’s.

Her husband Eddie White, a roughnecker, has rough sex with her when he’s not off in the oil fields where, several years into their marriage, he falls from a derrick to his death.

In addition to the lack of jealousy between Gid and Johnny — or perhaps a reason for it — there is the love they have for each other as friends and co-workers. They don’t engage in fistfights or other alpha-male testing that often goes on among the men in their region.

Leaving Cheyenne has two basic scenes repeated throughout the novel: Gid or Johnny with Molly doing a lot of talking that leads up to or follows after lovemaking, and Gid and Johnny doing things together in ways that, for them, are usually fun although sometimes irritating.

The novel is written in three sections — one when the three of them are in their 20s, the second when they are in their 40s and the third when they are in their 60s. During those three sections, there are occasional flashbacks to their time as children together, and, at the very end of the book, after one of the three dies, there’s a flashforward in the form of a last page that simply lists three tombstones with names and dates.

Who they are when the novel opens

As I said, it may be my fault as a reader, but I kept looking for more to happen. Well, for something to happen.

Gid, Johnny and Molly are who they are when the novel opens, and that’s who they are at the end. They’ve aged, and that is what the title’s about. There’s an explanation at the start of the book:

The Cheyenne of this book is that part of a cowboy’s day’s circle which is earliest and best: his blood’s country and his heart’s pastureland.

So, leaving Cheyenne is leaving behind the rich part of a cowboy’s day or, in this case, the rich part of the lives of Gid, Johnny and Molly.

OK, they get old, but not much changes, except that they aren’t as spry as they once were and they are approaching death. At the start of the novel, these three have an unconventional but comfortable relationship among themselves, and that’s what they retain throughout the book.

Other people

Other people appear here and there — Gid’s wife Mabel Peter, their daughter Sarah, their granddaughter Susie, Molly’s sons Jimmy and Joe — but they seem to be employed simply to heighten the reader’s attention on Gid, Johnny and Molly. They aren’t fleshed out much. In fact, Jimmy and Joe never show up on the novel’s stage; they’re just talked about.

There are two men who get a bit more attention from McMurtry: Gid’s hard-driving father Adam and Molly’s drunk father Cletus.

Adam Fry seems to have a preternatural knowledge of everything there is to know including whom Gid should marry. Cletus is a slobby and slothful man whom Molly nonetheless feels enough affection for that she remains when ever other one of her siblings has fled.

But each father dies a sad and violent death. And the novel is less for their disappearance.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.27.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.