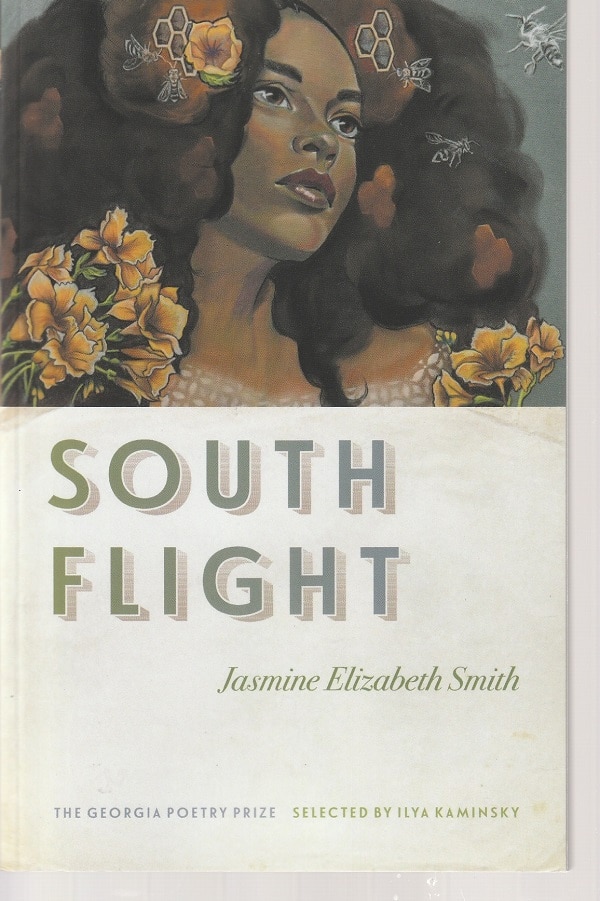

African American lovers Beatrice Verdene Chapel and Jim Waters are the central characters in Jasmine Elizabeth Smith’s anguished, violent, blues-infused poetry collection South Flight, published by the University of Georgia Press.

In “Love Letter on the Eve of Revolution,” Jim is writing to Beatrice as he is getting ready to escape the everyday murderous white rage of 1920s Oklahoma and take the train to Chicago — “head northbound without turning back.” This is the revolution of the poem’s title and the South flight of the book’s name.

Jim writes that “only blues/seems to make sense these days,” and, in a reference to the ever-present danger of lynching, he asks, “how can a strangled chord/progression picked in love//sound like something other/than violence?” And he ends his letter — Smith ends the poem — “I know this blues//sounds mean,/but how can I love on bended knees?”

South Flight, winner of the 2021 Georgia Poetry Prize, is an angry, heartsick lesson in the American history of brutal racial hatred, a history of routine lynchings and spasmodic massacres. It is told mainly through the relationship of Beatrice and Jim and centers on a corner of the South a century ago. Yet, these slashing, jagged poems aren’t recounting dry events in some chronology, lifeless and sterile. They are vibrant with the pain that has been the legacy of modern American Blacks, resonating with the anger at injustice that is at the heart of Black Lives Matter.

To underscore the deep roots of her story, Smith provides often detailed historical and literary notes for nearly half of the collection’s 49 poems. For instance, one note begins: “ ‘Beatrice Contemplates the Wild Dog Killing Prey’ is based on a May 31, 1921, incident in which mobs of white residents massacred the thriving all-Black neighborhood of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma.”

“Never say we do”

Another note says that “Correspondence from Chicago to Boley,” one of the last poems in the book, was inspired by Genesis 19:26, the story of Lot’s wife being turned into a pillar of salt for looking back at Sodom and Gomorrah. This poem opens with Jim writing, “there be many times I wanted to look back/but was worried it’d make spilled salt of me.” Chicago, though, has not been a paradise:

I’ve had a long day on the factory line.

it’s a thirteen-block drag home & I tire

of the smell of smokestacks, shaved steel.

pocket my hands, they just cold.

As that last line indicates, Smith adapts the language of working-class Blacks in many of her poems featuring Jim. For instance, the end of “Jim Writes His Marriage Vows” is his commentary on how racism pushes him away from Beatrice: “us can never say we do.”

Beatrice echoes this, in her own more grammatical lines in “Beatrice’s Prayer to Be Reborn in the South as an Old Cypress.” After reflecting on a body “who hangs, face near/and looming like ripe casket fruit among the web/worms” — an echo of the Billie Holiday song “Strange Fruit,” written by Abel Meeropol — she says: “Even your trapper blade can’t cut/the heart or the ugliness we’ve come to know.”

The book is in five sections, each of which is introduced by lines from a blues song, such as “Down Hearted Blues” by Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey’s “Moonshine Blues.” South Flight offers poems with a variety of structures, some flush right, some centered on the page, most flush left. On occasion, an entire poem will be in italic, or some lines within a poem.

“Like hackberries”

All such stylistic questions, however, are secondary for Smith who lets the pain of her characters and of all the Blacks of that era and of all Blacks today serve as the controlling factor in what has been put down on her pages.

In the book’s final section, Jim flirts with the idea of returning home to Beatrice, but, it seems, he never does. It’s dangerous, as Beatrice recognizes in “An Inventory of Her Blues,” a lament that includes the verse:

Weep for those who hang

like hackberries in locust trees,

their mothers’

washed black dresses & pillbox hats

The poem concludes with another reference to the violent white race riot in Tulsa that destroyed more than 35 square blocks of the neighborhood and left as many as 300 Blacks dead:

Weep for Greenwood.

For yourself & me, I sure do.

“One of your kind”

Throughout South Flight, white racism stalks Blacks, even Josephine Baker who fled the South to a career as a highly popular dancer and singer in Paris. In “Zouzou,” a reference to the 1927 French film starring the mixed race Baker, another Black is telling her to face facts: “When are you going see/you aren’t ever goin be one of them? Don’t mean a thing/they pour Prosecco in porcelain dishes./Let you lap leftovers from their palms.” Baker may wear Schiffli lace and dine on candied roses, but the advice-giver asks, “Do they call you beautiful/for one of your kind?”

Baker is lucky to have found success and riches in the white world. For Beatrice and Jim and most Blacks in the South, a constant threat is the hair-trigger potential for lynchings and massacres, convulsively commonplace in their world. Nearly half of Smith’s poems mention lynchings, massacres or the ghosts left behind.

“[Boley Ghosts Haunt Jim]” is a rare poem in South Flight that tells the story of a Black victory over whites. Members of Pretty Boy Floyd’s gang tried to rob the bank in Boley, and Smith writes how “whole town gathered outside farmers & merchant bank with bird guns & squirrel rifles” and shot up the robbers as they tried to escape — “we imagined shooting up the heart of the confederacy to tatty white funeral lace.”

But, even here, there are sharp echoes to six massacres of Blacks, listed in a catalog at the poem’s end, leading up to names of Smith’s two Black lovers: “greenwood & sulcom; rosewood & ocoee; elaine & sprinfield; Beatrice & Jim.” Five of these massacres occurred in the South. The sixth is an apparent reference to the three days of white rioting in 1908 in Springfield, Illinois, 200 miles south of Chicago, during which Black neighborhoods were attacked, Black people murdered in the street, and Black businesses and homes destroyed.

“Tossed in other mines”

Often, South Flight will offer a line or an entire poem all but exploding with agony and suffering. Even simply a title.

“Bodies Seen at or Disposal Sites: in Lack of Carnations” is exactly what the poem’s name says. After a note below the title gives its source: “after Computations as to the Deaths from the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot by Richard ‘Dick’ Warner,” the poem lists location after location after location, such as:

Placed under other railroad tracks,

in the fairgrounds under the Reserve

building on East 15th Street. In a hole &

tossed in other mines…

.

Disposed on the pier west of Tulsa on West 3rd

between Tulsa & Sand Springs in the hop clover & wild violets.

Each location represents one or more bodies although, until the end, none is mentioned in the poem, making the list eloquent in its silence. And then Smith adds her only overt commentary: “All are disposed in mass/graves/of nonhistories.”

“Mine to sell”

Perhaps even more eloquent are lines from “[Jim Imagines the Ghost of Robert Johnson at the Cross-Roads].” Johnson is the famous bluesman who reputedly sold his soul to the devil for guitar mastery, but the poem seems to gainsay that.

In Jim’s imagining, Johnson says “it easier to swallow hell/than a body/hanged down highway side.” He says his life of risky behavior had one cause: “what drive/my back into corners,/devil or dread, I was never mine to sell.”

That is the core of South Flight. More than half a century after Emancipation, the official end of slavery, American Blacks such as Beatrice and Jim were still enslaved in the chains of white racism, not owning the freedom to be themselves. And, today, more than a century later, those chains remain in place.

…..

Patrick T. Reardon

…..

Patrick T. Reardon

10.20.22

This review originally appeared in a slightly different form in Another Chicago Magazine on 9.20.22.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.