Back around 2800 BC or 2700 BC — in other words, nearly 5,000 years ago — lived a Middle Eastern ruler who later became the inspiration for the hero of the first great work of world literature The Epic of Gilgamesh.

This ruler may have been called Gilgamesh or maybe Bilgamesh. And he came along at the right time inasmuch as writing had developed to the point that a larger-than-life version of his story could be recorded and remembered in cuneiform on stone tablets.

Cuneiform, according to one increasingly popular theory among experts, began as an accounting method and only later, probably between 3300 BC and 3200 BC, was adapted to reflect the sounds of words and phrases of oral Sumerian. One later poem described Gilgamesh’s father as the inventor of this first written language although he was born several centuries later.

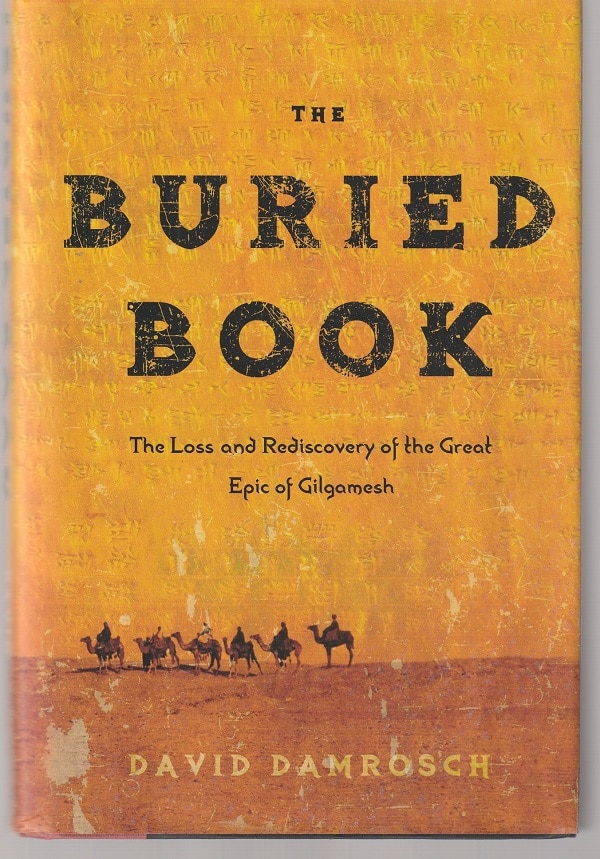

This written language in Gilgamesh’s time was, for the first time, being stretched for use in the creation of imaginative works, not just for trade and administration, writes David Damrosch, an expert on world literature at Columbia University, in his 2007 work The Buried Book: The Loss and Rediscovery of the Great Epic of Gilgamesh.

Early versions of the Gilgamesh story ended with the earthly king becoming the ruler of the underworld, known as the House of Dust. Damrosch notes:

“The Mesopotamian House of Dust is the earliest known version of the underworld realm that later developed into the Hebrew Sheol, the Greco-Roman Kingdom of Hades and Persephone, and the infernos of Satan and Iblis.”

For those Mesopotamians, death was it, and the underworld was the only place for the departed soul to go.

“To them, the Greeks’ sunny Elysian fields, Islam’s heavenly gardens, and the New Testament’s bejeweled New Jerusalem would have looked like wishful thinking, far less credible than their conception of the dark realm deep within the earth.”

A brilliant strategy

In other words, the gloomier philosophical and theological foundations of that civilization were radically different from the more hopeful core beliefs of the Judeo-Christian-Islamic culture that has dominated the globe over the last two millenniums.

Because of radically different world views, Gilgamesh, the actual person who lived nearly five millenniums ago, would have had a hard time understanding today’s world. And the same is true for 21st-century readers trying to grasp the meaning and import of the actions and scenes in the great Gilgamesh epic.

Damrosch recognized this when he set out to write his book about the Epic of Gilgamesh — about its 1,000-year popularity, its loss for 2,000 years and its rediscovery only about 150 years ago.

Instead of starting out, as I have in this review, telling the readers about the world that set the stage of the poem, Damrosch flips the chronology and tells the story backwards.

It’s a brilliant strategy, and, as a result, The Buried Book is a lively, very human, clear and compelling account that doesn’t overwhelm the reader with the foreignness at its heart. It begins with something much more familiar — the most recent part of the story, the first English translation of the epic.

This translation was worldwide news because it dealt with the story of a great flood that, in many ways, seemed to be a model for the much later account in the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Genesis. For some, it proved the accuracy of the biblical account. For others, it raised questions about the religious underpinnings of the Noah narrative.

And it still resonates today as Bible scholars, theologians and believers wrestle with the relationship of faith, myth, history, revelation and ancient texts.

“One of the most dramatic intellectual adventures”

The effort of early archeologists and other scholars, most of them Europeans, to unearth the Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets and decipher them was, Damrosch writes, “one of the most dramatic intellectual adventures of modern times: the opening up of three thousand years of history in the cradle of civilization.”

These endeavors resulted in the discovery of the massive library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in the long-buried ruins of Nineveh, near Mosul, and enabled the recovery of the region’s ancient history, culture and rich literature, especially The Epic of Gilgamesh.

“Gilgamesh links East and West, antiquity and modernity, poetry and history, and its echoes can be found in the Bible, in Homer, and in The Thousand and One Nights.

“At the same time the epic illuminates the profound conflicts that persist within each culture, and within the human heart itself. ‘Why,’ Gilgamesh’s divine mother Ninsun asks the sun god, ‘did you afflict my son Gilgamesh with so restless a spirit?’ ”

Gilgamesh’s quest

Initially, the epic was a sensation because of the flood narrative. But, once the full poem was translated, it was clear that The Epic of Gilgamesh was a masterpiece of world literature, addressing the core issues of the human condition, especially the inevitability of death.

It deals with a headstrong king whose adventures bring about the death of his beloved friend Enkidu, leaving Gilgamesh desolate and in a fruitless search for immortality.

“Gilgamesh’s quest may have failed, but along the way he learns lessons about just and unjust rule, political seductions and sexual politics, and the vexed relations among humanity, the gods, and the world of nature.”

Step by step back in time

Damrosch’s book has an introduction, seven chapters and an epilogue. The seven chapters take the reader step by step back in time to the writing of the epic and then to its sources:

- Chapters 1 and 2 (“Broken Tablets” and “Early Fame and Sudden Death”) focus on George Smith, the brilliant amateur and linguistic genius, who, in November, 1872, became the first person in more than 2,000 years to read the epic. The achievement made his career, but then set the stage for his early death on an archeological expedition.

- Chapters 3 and 4 (“The Lost Library” and “The Fortress and the Museum”) tells the story of the Assyrian archeologist Hormuzd Rassam, “the only prominent archeologist of his era who was of Middle Eastern origin.” Through intelligence, humanity, savviness and persistence, Rassam discovered Ashurbanipal’s library with its copies of the epic, but his fame and career were undercut by the chauvinist British establishment.

- Chapter 5 (“After Ashurbanipal, the Deluge”) details the history of Ashurbanipal and his family, of his building the library and of the ruin of the library and realm in the aftermath of the king’s death.

- Chapter 6 (“At the Limits of Culture”) is Damrosch’s account, nearly 200 pages after the beginning of his book, of the epic itself — of the story it told and the meanings that story held for the people of its time and the possible name of its author, Sin-leqe-unninni.

- Chapter 7 (“The Vanishing Point”) looks at the older cultures and literary works which laid the groundwork for the writing of The Epic of Gilgamesh.

“His distant image is refracted today”

An epilogue details how modern authors, such as Phillip Roth (The Great American Novel), have retold the Gilgamesh story, but its emphasis is on one surprising author in particular, Saddam Hussein.

In the decade before his defeat and execution, Saddam, an admirer of Ernest Hemingway, published several novels under his name (although, it appears, not composed by him except maybe in outline). Damrosch writes:

“It is Saddam’s first novel that is relevant here, for it blended elements from Gilgamesh with The Thousand and One Nights into an allegory of the first Gulf War.”

One CIA agent who spent three months studying the novel for a better understanding of the autocrat is quoted in a forward of the novel as describing it as “an elegantly written, intelligent book, that holds you right to the last page.”

The restless Gilgamesh was unable to find the immortality he sought, but, 5,000 years after his death, his epic has given him an eternal literary life, as Damrosch notes:

“His distant image is refracted today by authors as disparate — and as interconnected — as Philip Roth and Saddam Hussein, both children of Abraham, and both heirs of their common literary father, the globe-trotting Ernest Hemingway.

“If he sits today at Gilgamesh’s side in the House of Dust, Hemingway’s great predecessor Sin-leqe-unninni must be pleased to see how many people are…[reading] the story of that heroic youth, borne along by emotion, who scoured the world looking for life, then returned home to his city, weary but at peace, to set down his labors on a tablet of stone.”

Patrick T. Reardon

8.17.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.