His Black Love mural in the often-violent Cabrini-Green public housing development (1971) was described by one art expert as “an Afro-American Parthenon frieze.” And his All of Mankind: Unity of the Human Race, a series of interior and exterior murals in and on a small Catholic church nestled in development (1971-73), was compared to Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes.

Not only that, but Walker was the father of what Studs Terkel described as “the wildest, most exciting street art movement in the country,” a movement that has resulted in artworks covering blank walls in neighborhoods, particularly ethnic and low-income communities, from one end of the nation to the other.

Walker, who died in 2012, was one the most significant artists to work in Chicago over the past sixty years. Yet, few present-day Chicagoans know about him or about his art — or, for that matter, about the roots of the national mural passion that he midwifed.

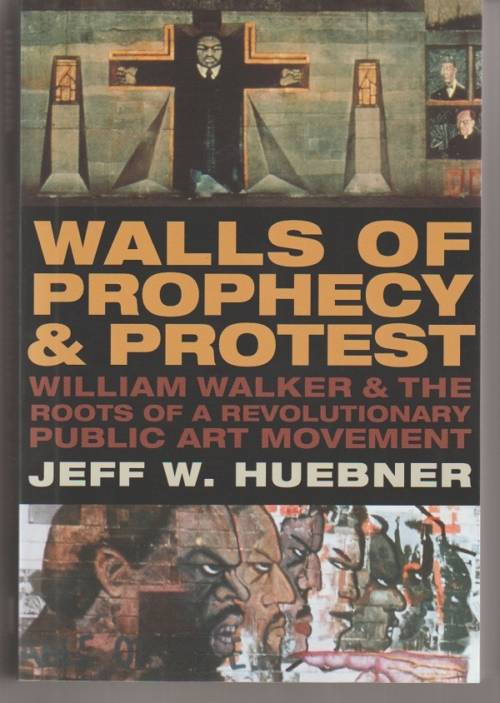

Jeff W. Huebner’s important, well-researched and affectionate Walls of Prophecy & Protest: William Walker & the Roots of a Revolutionary Public Art Movement (Northwestern University Press, 372 pages, $34.95) goes a long way toward making sure that Walker and the origins of the community mural trend don’t get lost in the fog of the past.

“Maddening humility”

Walker, as Huebner relates, was self-effacing and spartan but had a vision of steel when it came to art and its meaning for neighborhood people. In my long career as a Chicago Tribune reporter, I interviewed Walker a couple times, and Huebner’s reference to his “maddening humility” is right on the mark.

That, in part, is why Walker operated under the radar of much of art-conscious Chicago, even in his years of greatest productivity. Even more responsible, however, was his decision to focus his energies in the poorest of the city communities and to specialize in a form of art, outdoor mural-making, that, being out in rain, snow, heat and cold, has a short shelf-life.

Of all of the dozens of outdoor works that Walker created alone and with others, only three remain, each of them restored at least once — Childhood Is without Prejudice at 56th Street and Stony Island Avenue (1977), History of the Packinghouse Worker at 4859 South Wabash Avenue (1974) and Wall of Daydreaming and Man’s Inhumanity to Man at 47th Street and Calumet Avenue, created with Mitchell Caton (1975).

The artist as ascetic

Walker, Huebner writes, was “the stern moralist, the enamel orator,” who loved “the human side of street life in the city” and once explained, “I’m painting for black people.”

Walker, Huebner writes, was “the stern moralist, the enamel orator,” who loved “the human side of street life in the city” and once explained, “I’m painting for black people.”

His life was that of the artist as ascetic, as Huebner, who knew him well, notes:

“Walker sacrificed himself almost entirely to his art, eschewing opportunities for steady wages, university affiliation, self-promotion, and a national career as well as close personal ties…He cared more about working in Chicago’s toughest neighborhoods, close to his roots and his people, often late into the night. There he could interact with a broad cross-section of humanity, from the lowest street characters to the highest of political bosses; Walker knew, talked with, wrote about, and painted them all.”

Walker’s art could be angry, and he courted controversy with works that portrayed the violence, crime and exploitation in low-income African-American neighborhoods. In other murals, though, his gentleness and belief in the essential goodness of all people shown through.

Both aspects are on view on the cover of Huebner’s book — at the top, an image of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. inside a cross-shaped niche from Walker’s St. Martin Luther King at 40th Street and Martin Luther King Drive (1977-78), and at the bottom, a section of angry black faces that, in Wall of Truth, created by Walker and other artists at 43rd Street and Langley Avenue (1969-1970), confront a parallel series of angry white faces.

“An unpardonable act”

Wall of Truth was across the street from Wall of Respect, the collaborative mural created on the side of a two-story tavern in the impoverished South Side neighborhood of Grand Crossing by Walker and nearly two dozen other younger black artists and photographers. Produced with direct community input, Wall of Respect was completed on August 24, 1967, and sparked the community mural movement.

The idea for the mural was Walker’s, and it was Walker who stayed with the work as its guardian, revising and replacing his sections, as most of the rest of the artists moved on to other projects.

It was one of the high points in Walker’s artistic career — and also the most emotionally devastating.

It’s a story that was told in depth for the first time last fall in The Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago, edited by Abdul Alkalimat, Romi Crawford, and Rebecca Zorach, also published by Northwestern University Press. And Huebner devotes a long chapter to the controversy.

Shortly after Wall of Respect was finished, Walker gave permission, for reasons still not clear, for a section, painted by Norman Parish Jr., to be whitewashed and told another artist to paint new images there. It was a decision that “haunted” Walker for the rest of his life. As he told Huebner in an interview for a Chicago Reader story in 1997:

“It was one of the greatest mistakes I’ve ever made, and I’m truly sorry. I’ve carried that burden all these years. It was not right. To be perfectly honest, and I want to be fair, he had a right to be upset. It was an unpardonable act…He really did have a nice section.”

The Wall of Respect was lost in 1971 when the tavern building, damaged by fire, was razed.

“Circular heads of four figures interlocked”

Another important artwork that’s been lost is what many describe as Walker’s masterpiece All of Mankind. Its most visible element, Huebner writes, was the church’s 50 foot-by-60 foot façade:

“The central image formed one of [Walker’s] motifs: in a symbol of brotherhood, the circular heads of four figures representing different races — black, Asian, Latino, and white — were interlocked Venn diagram-like while their hands embraced each other, against a painted faux stained-glass window backdrop.”

Also included were symbols from six major world religions as well as the names of martyrs for justice and equality, including slain civil rights workers, Jesus, Gandhi and three policemen killed at the development by sniper fire. In a 1972 report, the church pastor wrote that Walker “worked on the wall every day for five months with constant community participation. The wall belongs to the community. They protect and celebrate his art. He expresses their hopes and loves.”

Either directly or indirectly, all of Walker’s art was aimed at expressing the hopes and loves of the black people for whom it was created. He sought to be a voice of the voiceless, putting paint on bricks, knowing that his was the sort of art that would not bring riches. Huebner’s book is a significant addition to understanding the history — not just the art history — of Chicago. It gives Walker’s art more permanence than it had in the physical world.

In December, 2015, the All of Mankind façade, his masterwork, was whitewashed away, apparently to make the property easier to sell to land developers.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.13.19

This review first appeared at ThirdCoastReview on 10.18.19.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.