Herman Wouk’s short science-fiction allegory The “Lomokome” Papers was written in 1949, just four years after the United States dropped two atom bombs on Japan, ushering in the nuclear era. That was also the same year that the Soviet Union successfully tested its first atom bomb.

Seven years later, the 18,000-word story was published in Collier’s Magazine on February 17, 1956. By this point, the international nuclear arms race was well underway.

In 1968, fears of nuclear annihilation were still high, but even more in the front of the public consciousness was the Vietnam War and the extensive protests that had arisen against it. For instance, three years earlier, folk singer Phil Ochs released one his most popular songs “I Ain’t Marching Any More,” an anti-war ballad that included the chorus:

It’s always the old to lead us to the wars.

It’s always the young to fall.

Now look at all we’ve won with the saber and the gun.

Tell me, is it worth it all?

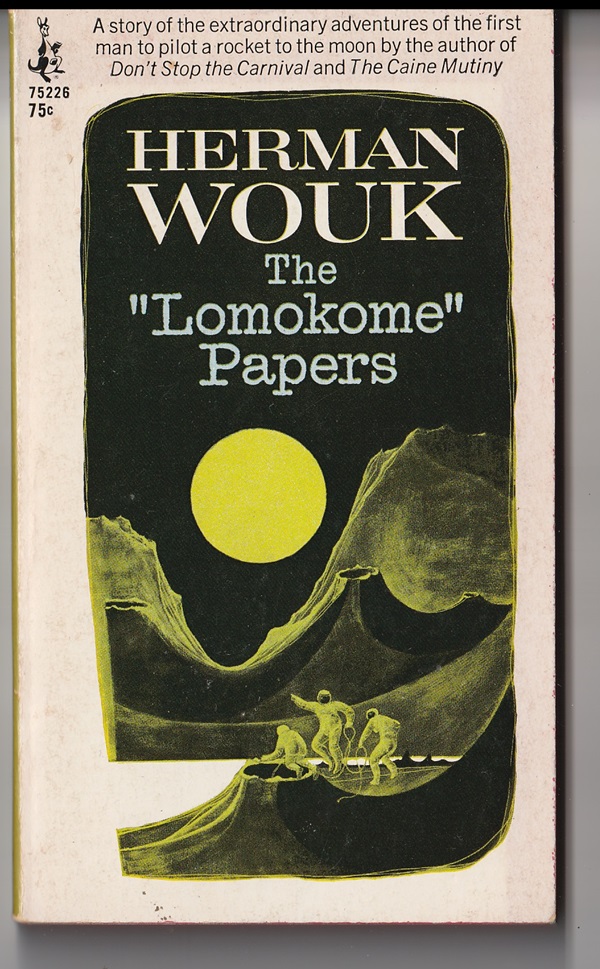

To capitalize on both interests, Pocket Books published The “Lomokome” Papers as a handsomely designed paperback, featuring 16 mannered illustrations by Harry Bennett.

Handsome as it was, the book never clicked with the reading public and was never reprinted after 1968, even though Wouk was a master of the bestseller, with such titles as The Caine Mutiny, Marjorie Morningstar, The Winds of War and War and Remembrance.

I read the book shortly after it was published and was underwhelmed. I read it again recently and found it interesting as an oddity, as a fable that wasn’t fabulous enough.

A complex set of documents

Maybe that had to do with its complexity.

As short as it is, The “Lomokome” Papers is made up of several documents, all contained in the fictional Appendix “E” of the Official U.S. Navy Report: “Extragravitational Propulsion for Military Purposes.”

The full report, because of its information about the technical breakthroughs that made it possible for the U.S. to send two rockets to the Moon (on May 23, 1954, and October 17, 1954), is being kept secret. However, Appendix “E” is being released to end rampant speculation about the Moon flights. It contains:

- A foreword by the Chief of Navy Operations, Admiral Jonathan S. Wells.

- A preface by Professor V. W. Robinson of the Montana Institute of Technology,

- The “Lomokome” Papers, which contain:

- A foreword by the editor of the papers, Navy Lt. William T. Dawes.

- The papers themselves, written by Navy Lt. Daniel More Butler while on the Moon. They are made up of 107 sheets of paper which are a diary by Butler covering more than three months, a narrative containing many gaps due to missing sheets. Most of the papers deal with Butler’s growing knowledge of the people he discovered living under the surface of the Moon, a nation called Lomokome, and their enemies, a nation called Lomadine. But they aren’t all written by Butler.

- About a third of the papers, roughly 6,000 words, are Butler’s transcription of The Book of Ctuzelawis, a sacred text for both the Lomokome and the Lomadine.

The Book

The underworld of the Moon had been the scene of wars for thousands of earth years, narrowing down to only two disputants, Lomokome and Lomadine, around the time of Christ. In 347 A.D., the contenders developed atomic bombs. Then, at some point, with the development of a silicone bomb, both sides knew the next war would totally destroy their civilizations.

At that point, The Book of Ctuzelawis — written by an old man who had been the child of a Lomokome father and a Lomadine mother and was raised on the surface of the Moon, away from both nations — provided a safe solution.

Instead of the wasteful inefficiency of regular war, he proposed a new way in which, once war was declared, a College of Judges would detail tasks that both sides would have to carry out, as if in preparation for actual fighting. But no fighting would take place. Instead, at a deadline, the College of Judges would decide, very scientifically, which of the two sides would have won.

Each time since then, the loser, knowing that it had seemingly no chance to win, accepted the ruling. And — here’s the key part — submitted the required number of young people as well as the required number of older leaders of the nation for execution.

These executions, carried out very ceremoniously and bloodily, involved a lot of throats slashed. But, at least, it responded to the age-old complaint of the foot soldiers, contained in the Ochs song:

It’s always the old to lead us to the wars.

It’s always the young to fall.

“Infant’s flesh”

In his own foreword to the book, Wouk said he was inspired by Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal, a 1729 satirical essay suggesting that the poor people of Ireland could ease their economic troubles by selling their children as food for the elite. Here’s an excerpt:

I have reckoned upon a medium, that a child just born will weigh 12 pounds, and in a solar year, if tolerably nursed, encreaseth to 28 pounds….

Infant’s flesh will be in season throughout the year, but more plentiful in March, and a little before and after; for we are told by a grave author, an eminent French physician, that fish being a prolifick dyet, there are more children born in Roman Catholick countries about nine months after Lent, than at any other season; therefore, reckoning a year after Lent, the markets will be more glutted than usual, because the number of Popish infants, is at least three to one in this kingdom, and therefore it will have one other collateral advantage, by lessening the number of Papists among us.

A Modest Proposal is probably the best and best-known satire ever written in English. It is so well-known because it is so over the top in presenting its horrific and ridiculous proposal in the voice and tone of the anti-Catholic establishment. This is why it’s so good.

An adventure, satire and sermon

Wouk falls far short of his model. To be fair, he writes that he aimed to offer readers “a romantic adventure, a social satire [and] a utopian sermon.”

The science-fiction aspects of the tale work in an interesting way but get lost in the humorless details of The Book of Ctuzelawis. Wouk notes that Lomokome in Hebrew means Utopia or Nowhere. And perhaps he thought the non-war war that the Book demands made a lot of sense.

His idea of non-violent rules that everyone would follow and of non-battlefield executions are simply pie-in-the-sky. But not wild enough, not like using Irish babies for food!

In fact, every foot soldier has complained about dying on the front lines while the leaders, military and political, are far away from danger.

Every foot soldier has dreamed of the leaders paying the price as well.

No shock value in that proposal.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.30.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.