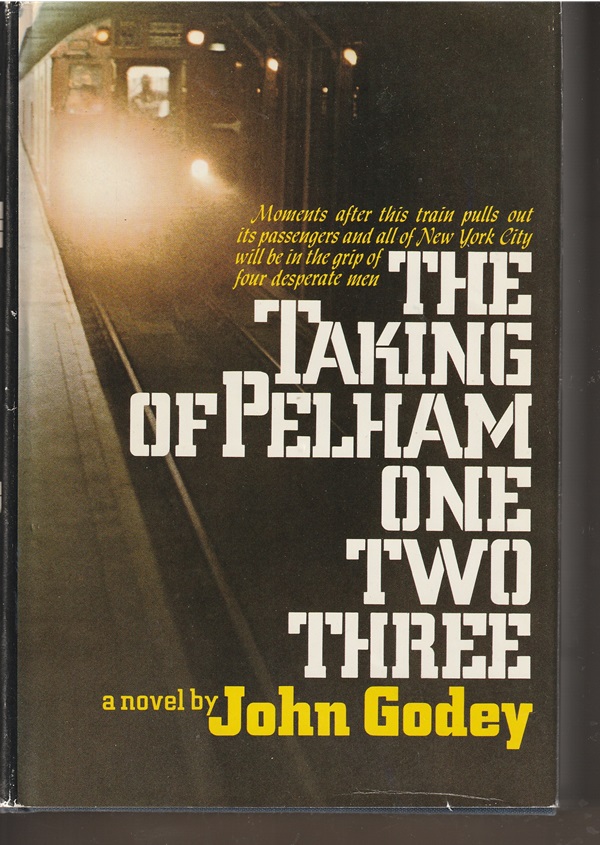

A thriller written more than half a century ago, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three by John Godey still thrills today. And it’s also something of a time capsule, capturing an era that is now passed but helped create our present time.

Godey (real name: Morton Freedgood) published his novel in 1973 at a time when airplane hijackings were routine items on evening newscasts. But he gave his book a much different and more unexpected twist, centering his story on the hijacking of a New York City subway train.

Pelham 123 is the call sign of the targeted train, meaning it departed its originating station, Pelham Bay Park, at 1:23 pm.

The four hijackers are after money — $1 million, the equivalent about $7 million today. Their plan is cooked up by two men who meet in a welfare line: Ryder, a mercenary who’s having a tight time in a weak soldier-of-fortune job market, and Walter Longman, a timid, disgruntled former motorman who got pushed out of his Transit Authority job.

So timid is Longman that, just as the hijacking is about to take place, he thinks to himself, “I’m going to die today.” As it turns out, he survives, but five other people are gunned down, some innocent, some not so innocent.

“Swaggered standing still”

For the crime, Ryder, the alpha-male leader, recruits Steever, an unimaginative but capable heavy, and Joe Welcome, a cocky gunman, so much a smart-mouth that he was thrown out of the Mafia and so brash that Ryder thinks of him as “a man who swaggered even when he was standing still.”

They take over the train in a tunnel between stations, detach the back nine cars and keep only the front car with their hostages, 16 passengers and the motorman. They demand the money in an hour and vow to start killing hostages for every late minute.

It’s a catchy concept, and Godey’s novel has been made into a movie three times:

- The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974), starring Robert Shaw as the Ryder character, called Mr. Blue, and Walter Matthau as Lt. Garder, his nemesis;

- The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1998), starring Vincent D’Onofrio as the Ryder character, called Mr. Blue, and Edward James Olmos as his nemesis, Detective Anthony Piscotti;

- The Taking of Pelham 123 (2009), starring John Travolta as Ryder, also called Mr. Blue, and Denzel Washington as Walter Garber, an MTA subway dispatcher, his nemesis.

The novel and the movies

Goday’s novel features sharp narrative cuts between the hijackers and those trying to stop the hijacking and builds up the growing tension as the deadline approaches for the delivery of the $1 million. So do the movies.

However, the book is filled with a large cast of characters, and the reader gets to listen in on the interior monologues of each of the criminals as well as some of the hostages and many of the cops and transit officials. The movies simplify things a great deal. In each, there is a mano-a-mano element to the clashes between Ryder and his nemesis. In the novel, there is no single person on the police side of the equation who confronts Ryder. It’s a man against the system.

However, the book is filled with a large cast of characters, and the reader gets to listen in on the interior monologues of each of the criminals as well as some of the hostages and many of the cops and transit officials. The movies simplify things a great deal. In each, there is a mano-a-mano element to the clashes between Ryder and his nemesis. In the novel, there is no single person on the police side of the equation who confronts Ryder. It’s a man against the system.

Knowing what’s going on inside the heads of so many of the characters, including the criminals, the reader, to some extent at least, is cheering for the hijackers succeed — at least, until shots start to be fired — while at the same time cheering for those trying to foil what seems to be a perfect scheme. The movies accomplish this by getting the viewer to identify with the Ryder character and his nemesis.

The movies don’t even attempt interior dialogues which results in a much less complex story. Also, Godey revels in communicating to the reader, through his characters, all the nuts-and-bolts details of the operation of the highly complicated New York City transit system. Such details are interesting in and of themselves, especially for New York readers, but the films have little room for such arcana.

At the same time, because of its quick-cut style, Godey’s novel is cinematic. The quickness of the cuts from one person and scene to another adds to the rapid pace of the storytelling. And it’s an approach that worked well for the author in 1973, and still does today.

A moment in American time

A particular pleasure of reading the novel a quarter of the way into the 21st century is how it captures a moment in American time. For instance:

- An undercover cop’s girlfriend who is a revolutionary in a mild, gentle way with books by Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin and Eldridge Cleaver on her bookshelves.

- The cop’s assignment to the East Village which, although today gentrifying, was known as the home of “the Ukrainians, the motorcycle freaks, street people, addicts, weirdos, students, radicals, acidheads, teen-age runaways, and (a) dwindling hippie population.”

- A hostage, Komo Mobutu, who sees himself as “a righteous working revolutionary, and even if he had the bread, he would still ride the people’s conveyance, and, for long-distance, he would still fly Greyhound.”

- Lt. Clive Prescott of the Transit Authority, an African-American, who finds himself pleased to watch the reaction of three Irish pols from Boston “as he stepped forward to greet them…[and] they were not quite able to conceal their surprise at this being somewhat different from what they expected — a shade different.”

- Some, but not all, NYC patrolmen who were equipped with the latest in technology, two-way radios.

- The trainmaster who, in talking with Ryder over the radio, asks him if he is a member of the Black Panthers.

- Ryder who, it turns out, was an American advisor in the then-still-raging Vietnam War.

- A middle-aged woman bystander who has “a towering blond beehive coif.”

For those, like me, who can remember that time, it was an era of gentle radicals, clunky technology, overt racism, revolutions that were trying to get traction and beehive hairdos, called by the hoity-toity coifs.

At the time, we didn’t know what was going to happen with all that stuff and so much else. For younger people, though, it’s all history, and they know how the hopes and dreams of that time turned out.

Patrick T. Reardon

9.3.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.