It was one of those encounters that one has in an art museum.

On a day in which I looked at hundreds of paintings and sculptures at the Uffizi Museum in Florence, I saw many images that I had seen before in art books — Titians, Botticellis, Raphaels, Tintorettos, a wealth of Renaissance works.

And then there was this one in particular that was totally new to me.

Here is the photo I took during that recent visit and cropped to post on Facebook. If you look closely enough, you can see the small reflection of the lights of the room in the glass covering the canvas.

The high point among many, many high points

There is something in the woman’s face, a thoughtfulness, a bit of mournfulness maybe, an inwardness, that connected with me. Hers was a beautiful face, or beautiful enough — with her fresh flesh tones, her red-pink lips, a straggle of curls before the ears on each side of the face, a strong chin, intelligent brown eyes.

She looked like someone I knew or could know or would want to know. She was probably the high point of my eleven-day visit to Florence which had many, many high points.

Searching for information about her, I found a reference on Wikipedia that indicated the portrait had been misidentified at one point as Giulia de’ Medici. Perhaps that was how she was titled in the past. My huge, nearly thirty-year-old, 647-page copy of Paintings in the Uffizi and Pitti Galleries by Mina Gregori does not include the portrait.

Ortensia

Now, she is identified as Ortensia de’ Bardi da Montauto, the wife of a banker in a family of bankers who had a close friendship with Michelangelo and his admirer and friend Alessandro Allori.

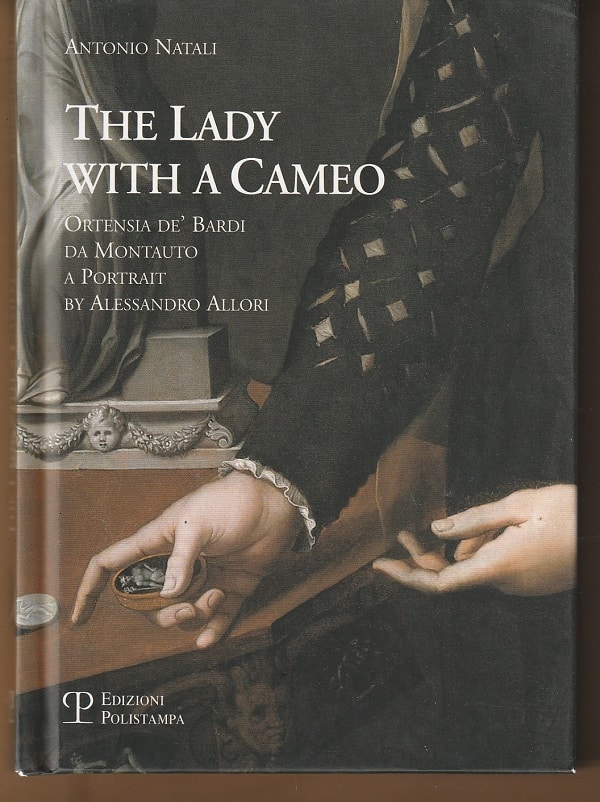

And I learned that there is a small book about her portrait: The Lady with a Cameo: Ortensia de’ Bardi da Montauto, A Portrait by Alessandro Allori by Antonio Natali. It was published in 2006 by the America-based Friends of Florence Foundation which has bankrolled a lot of art exhibition and restoration in Florence, including the work done to restore Ortensia’s portrait.

The handsomely produced book totals just over 100 pages and features an Italian text on the leftside pages and an English text on the righthand pages.

Most of those pages are the story of how the subject of the portrait and its artist were identified, as told by Natali, an art historian who was the director of the Uffizi from 2006 to 2015. The restoration of the painting is the subject of a short section at the end by Mariarita Signorini, who today is president of Italia Nostra, a non-profit organization dedicated to the protection and promotion of Italy’s historical, artistic and environmental patrimony.

A document from 1675, more than a century after the painting was created, indicated that it was “by the hand of the elder [Agnolo] Bronzino and by some believed to be by Michelangelo.”

Detective work

Through a neat twist of detective work, a close examination of a chair in the scene, it was possible, Natali writes, to determine that the painting was executed in 1559.

More sleuthing revealed Allori to be the painter, although the Bronzino attribution was understandable since Allori was his favorite student. Similarly, the speculation that Michelangelo may have painted the work made sense inasmuch as Allori filled the portrait with references to the painter-sculptor’s work.

Natali writes that there was “clear evidence of the relationship between Buonarroti and Alessandro in Rome.” After all, Allori

had gone there specifically to study the Michelangelo’ marvels and must have been aided in this…by the master (then a grand old man) in person, from whom he may have obtained permission to see private items and surviving drawings from his atelier…

There is no escaping the fact that Buonarroti is the undisputed protagonist in Allori’s series of citations [in the portrait]; to the point that it is almost natural to ask whether the unlikely conjecture of the attribution of the Uffizi painting….can be related to the resounding echoes of the master’s presence.

In a preface, Antonio Paolucci, then-superintendent for the Polo Museale Fiorentino, describes how Allori’s portrait captures the “gelid melancholy of this austere and beautiful lady.” Signorini, in her description of the restoration, mentions the “luminosity that seems to glow from within” and the subject’s “big, melancholy eyes.”

To me, there is definitely a glow from within, and, as for the melancholy — the face communicates to me someone who is in touch with sadness but also joy, with worries and pleasures, someone with a rich interior life in the midst of the busy bustle of a banker’s household.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.19.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

It’s many years, well decades, since, I visited the Uffici. This transfixed me, never understood why it is not more famous.

Alec — I totally agree. Pat