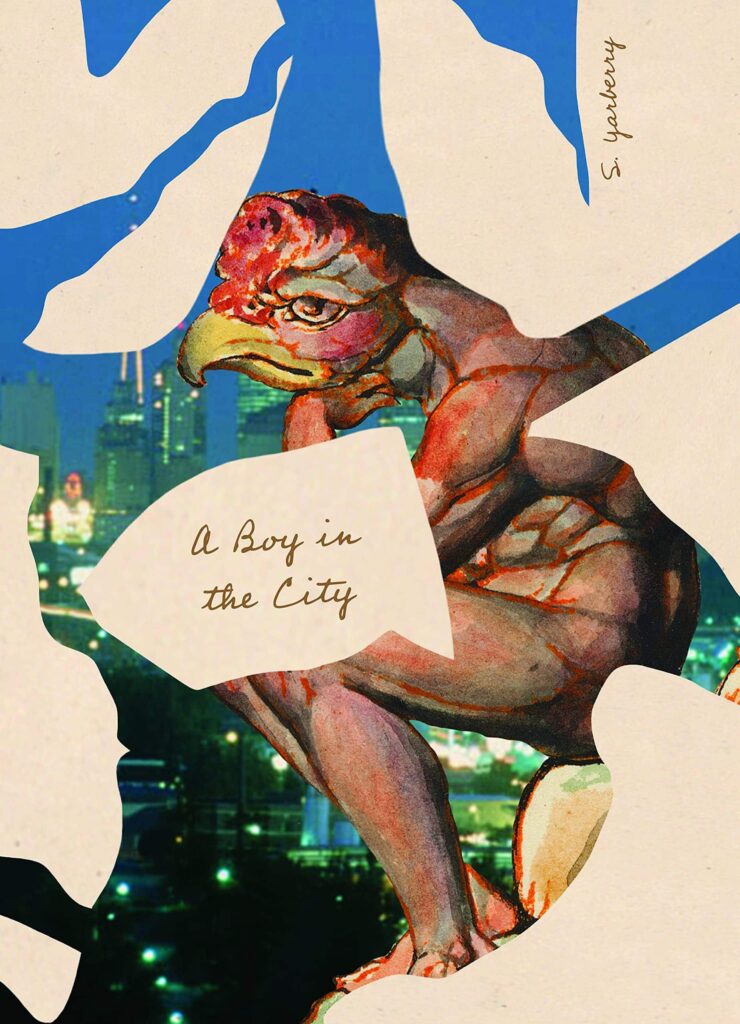

The pain that S. Yarberry suffers as a transgender person is strikingly described in their new book of jagged, anguished poetry A Boy in the City. It is pain set within the context of other, related emotional torment, including the end of a highly sensual, deeply physical, often confusing relationship with a girlfriend.

“Inside your mouth/lives something to say, though/you don’t say it.”

A Boy in the City is a scream of misery, or maybe a moan, or maybe sob, at times almost matter of fact, at others intensely visceral.

In the opening poem “The History,” Yarberry writes: “Anyways, your/thoughtless hand— brushes/across my breast, the breast I hate.” Later, in one of two poems titled “Down Below,” Yarberry writes of being “my own nightmare/for most of my life,” and describes walking through a park, a field, apparently in St. Louis:

A good

Midwest thunderstorm

creeping over the arch.

All I’m thinking is: can you

tell I don’t have

a cock in these jeans?

In “Icarus,” a title that references the mythical boy who flew too close to the sun, the poem ends with the jarring statement: “What am I if not a broken boy?”

Yarberry, originally from Orange County, lived for a time in Portland, Oregon, got an MFA in poetry from Washington University in St. Louis and is the poetry editor of The Spectacle. They are working toward a Ph.D. at Northwestern University where they hold a Mellon Cluster fellowship in Poetry & Poetics.

Inspired by Dante, Homer and Blake

And it’s clear from five pages of notes about many of the book’s 51 poems that Yarberry’s work is rooted in a deep study of world literature and art. For instance, the note for “Self-Portrait (Punching Ball),” one of two poems with a version of that title, indicates it is the first of several ekphrastics on works by British-born painter and writer Leonora Carrington and German surrealist Max Ernst who were lovers. An ekphrastic is a poem that describes or is inspired by another work of art.

The notes also show that Yarberry drew inspiration from a wide variety of writers, including Dante’s Inferno, Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad, The Obscene Madame D by Brazilian novelist Hilda Hilst and especially the works of visionary English poet, painter, and printmaker William Blake. Indeed, I suspect that a reader more versed than I am in Blake’s writings would recognize rich allusions to them in Yarberry’s poems.

Nonetheless, a reader doesn’t need to match Yarberry’s literary erudition to feel the heat and ache of these poems, their sharp jolts and erotic rhythms.

There are a wealth of lines to stop readers in their tracks, such as “The rain coming down like a violence” (“Stage Directions”), “The geckos are clicking. Crickets are starting/their naughty tune” (an untitled interlude), “The city lies open/like it’s baring its chest to me” (“I Despair! I Disengage.”), and “The sky/pink as girlhood and purple/like an adult bruise” (“Island of Calypso”).

Yarberry offers two groups of poems, interspersed in A Boy in the City — 42 with titles and another nine without titles that are called in the notes “interludes or disruptions.” In the table of contents, each is listed as “Chapter.” The titled poems are written in the first person and have a lot of elbow room on the page, as if looking over the vast stretch of a city from a high place. The interludes are in the second person, written shorter and more tightly, and give a claustrophobic impression of taking place, at least metaphorically, in a closed room.

“A modern catastrophe”

As the title suggests, the city, generic and gritty, is an important theme in Yarberry’s book, such as in “City-Builders” which opens with these lines: “When your body meets my body/the world goes blank, we build a new landscape.”

One picks beetles while the other selects rays to inhabit the city. “I don’t have the words/for what we are building.” As the poem ends, the lovers are on a fire escape, drinking beer, companionable, but not saying what needs to be said.

Instead, we sit and listen to the sound

of some structure, a few blocks

down, get its walls busted in.

These lines come in only the third poem of the collection, but they are shadows of the future, the razing of the relationship. Of course, those shadows are also present in the collection’s second poem, “Lips Crash With Lips, Inevitable.” Like many others, it highlights the couple’s fevered lovemaking: “This is what we want: sex, then rest. Sex, then rest.” Even so, the poem begins: “A modern catastrophe, we are, you and I.”

I don’t think any of the poems in A Boy in the City expresses any peacefulness, for all the couple’s frantic sex. One interlude includes the lines, “When she appears in front of you/she says Did I scare you? You say/You scare me all the time.” Similarly, in “Intimacy Abstract,” there are the lines: “You say my name./You are in full command./There’s nothing rosy.”

Late in the book, in “The Orchard,” it comes as a surprise, and yet not a surprise, that it is Yarberry who breaks the relationship. “How come/I couldn’t love her?” Nevertheless, the pain of the relationship is followed by the pain of the breakup, as in “Sphinx”: “Good-bye sticks to me/like ticks on a deer.”

And it seems that both of those sufferings were preceded by Yarberry’s lifelong pain.

“The Scholar” is a two-page poem about suicide, including the lines:

When the trees blow back and forth

in the cold November wind I think them

torsos and heads shaking wildly in my window….

Of course, I want to die. The trees

swerving. Nightly, I string myself up.

In other poems, the poet writes “I am both pedestrian/and animal. Sad zoo.” (“A Cloak You Cannot Take off”) and “To your left you see/the sky. Dangerous. The phone rings./It rings like it wants something from you.” (an untitled interlude).

“I was. I was.”

How much does all this pain have to do with the poet’s transgender nature and how much with other causes? That’s not made clear in the poems. Yarberry is never not transgender, and, yet, most often, this reality is implicit rather than expressed.

The final poem of the collection is the only one to directly deal with this, as its title indicates, “Trans Is Latin For Across.” And, in this poem, for once, Yarberry seems to find a place of equilibrium:

It’s not that I became

anything. I was. I was.

And the poem ends with the lines, “It is nothing special/to not want to be hurt.”

Patrick T. Reardon

8.26.22

This review originally appeared in Third Coast Review on 7.26.22.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.