It was nearly 40 years ago that I first read James Agee’s autobiographical novel A Death in the Family.

Since then, I have experienced a similarly sudden violent death in my own family. What had been, in my early 30s, an achingly sad and beautiful novel that conveyed what it felt like to go through such an event became for me, at the age of 70, something of a reliving of my own family’s tragedy.

A Death in the Family is based on Agee’s own experience when, in Knoxville, 1915, his father, coming back from visiting his ill father, was killed in a traffic accident.

Agee first dealt with his father and that time in his life in “Knoxville: Summer of 1915,” a short prose piece that was published in late summer, 1938, in The Partisan Review. Ten years later, he began working on the novel which was nearing completion at the time of his own sudden death, from a heart attack, in 1955.

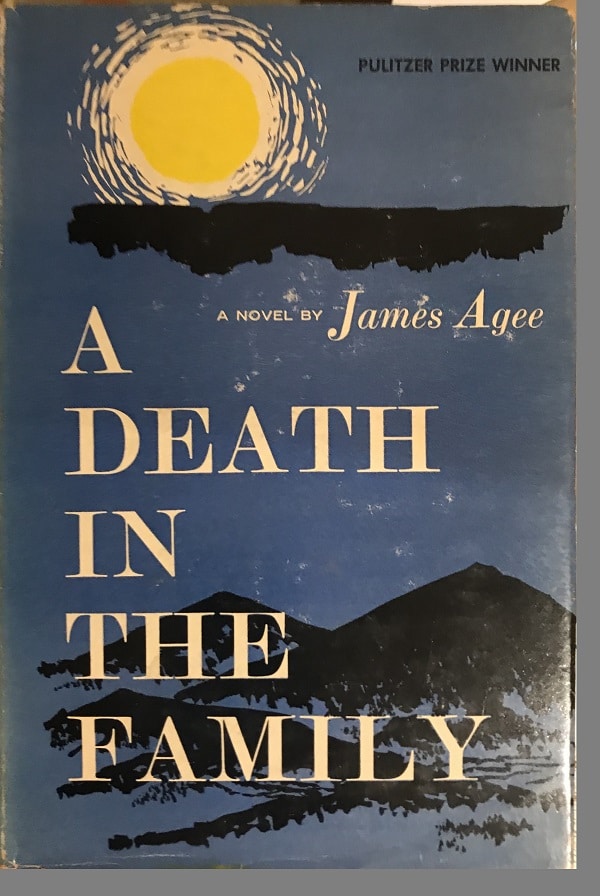

With the blessing of Agee’s widow, his protege David McDowell, one of the founding editors at McDowell, Obolensky, did the final edit on Agee’s work and published the novel in 1957. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

A work of high literary art

A half century later, Michael Lofaro, a professor at the University of Tennessee, published a version of the novel titled A Death in the Family: A Restoration of the Author’s Text. Based on Agee’s manuscripts and notes, this version, which puts the events of the book in chronological order and includes material that McDowell left out, is, according to Lofaro, more authentic.

That might be true. However, as a writer who has worked with editors my entire professional career, I know that editors usually help a manuscript although sometimes they can hurt. In this case, the McDowell version of the novel has been cherished and honored for more than six decades. It would seem that the editor didn’t hurt the work.

Also, after having just re-read the book, I’m disquieted by the idea of a version that has the elements in chronological order. I found the McDowell text powerful in its narrow focus on the evolving story of a little more than 24 hours.

The father, Jay, gets a dark-of-the-night call from his rural relatives about his own father being near death. He drives to visit him and finds him doing much better. And, then, off stage, Jay is killed on his drive home, when the steering mechanism of his auto fails. In another late night call, his wife learns that Jay has had a serious accident and sends her brother to find out what happened — and, when the brother returns with news of the death, each person of the family, most particularly Rufus (the stand-in for Agee himself), begins the process of trying to take in, understand and cope with the new reality.

This story is told in three parts — the day before the accident, the dark hours of learning of the death and, a few days later, the funeral. Opening the novel and then dividing these three parts are one short and two long italic sections which recall earlier events.

I find it difficult to imagine how a chronological version of this story would have the same power as the 1957 version. But I have not read the Lofaro version. Perhaps it is as good as the earlier one.

Without question, A Death in the Family, as published in 1957, is a work of high literary art, a rich and painfully felt evocation of childhood, innocence and a shattered world.

“And the next instant”

Having gone through our own family’s tragedy — my brother’s suicide in 2015 — I found Agee’s novel deeply resonant with our and my experience. It’s not especially that elements of the story match up at all with our shock. It’s that Agee exhibits an intense psychological awareness of what such trauma and grief do to the human psyche.

I found it to be a very complex thing to go through, comprising many contradictory elements.

Something of this is communicated in Agee’s novel in a scene in which Jay’s brother-in-law Andrew is telling his sister Mary, Jay’s wife, what he learned of the details of the accident and Jay’s death from a concussion that left him all but unmarked.

The emphasis throughout the conversation is that death was instantaneous, that Jay had no suffering, indeed, no idea of what was happening to him.

“Instead of [a painful death], Mary, he died of the quickest and most painless death there is. One instant he was fully alive. Maybe more alive than ever before for that matter, for something had suddenly gone wrong and everything in him was roused up and mad at it and ready to beat it — because you know that of Jay, Mary, probably better than anyone else on earth. He didn’t know what fear was. Danger only made him furious — and tremendously alert. It made him every inch of the man he was. And the next instant it was all over.”

These few sentences contain much. They exemplify the tendency of the survivors to try to understand how the dead person went through the death. What did that person feel? What did that person think?

There is also the impulse to focus on elements of the story that make it easier to take in, such as the painlessness of Jay’s death. And the impulse to see, in those moments of death, some essential feature of the person — in the shock of the crisis, Jay would have been angry and alert to solve it.

“Maybe more alive”

I am most deeply struck by Andrew’s thought that Jay may have been “more alive than ever before” in the moment before he died.

This may simply be a kind of wishful thinking on his part, but I wonder if it is not true. When someone is about to suffer sudden death, is there a moment of heightened awareness to the living of living? Are all senses on alert and brought into sharp focus?

And, if this might be true at the moment of sudden death, what of other sorts of death? Does the 81-year-old man dying of congestive heart failure sense/know/learn from his body that he is about to breathe his last and intensely feel that moment?

James Agee’s A Death in the Family was a hard book for me to read this time. Its sorrow and grief were endlessly deeper this time for me, and it is certainly a book of sorrow and grief.

Yet, as the few sentences from Andrew indicate, it is also a book about living — about the boy Rufus struggling mightily to understand the world, about he and his family maneuvering through the confusion of feelings at any moment of life and even more so in a crisis, about the people of this novel as well as its writer and its readers living with the reality of death, near or far.

And about taking the grief of living and turning it into art.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.28.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Good work and good time with your book on the truth of life journey as death is a true gift from lord to bless the human beings in the next life

Nice analysis. Thank you. An error of grammar needs to be corrected:

Rufus struggling mightily to understand the world, about he and his family maneuvering through the confusion of feelings at any moment ….

Should be “about him and his family.” About is a preposition and needs an apology object

No, it should read “his” as it refers to his maneuvering as in “about his and his family’s maneuvering ….”

*objective

I loved this. I too strongly identify with the events. My mother went to bed feeling a little sick and my dad found her in a coma and died on the way to the hospital. Alive one moment and dead the next. The loss has left me grieving still and I am 74. Thankfully I didn’t suffer like James Agee and die young of excesses. Great review of the book. I’m leading a discussion of the book in my book club and your essay helps.

Thanks, Gary. I’m glad the review is helpful. Pat