For one reason or another, I’ve owned a copy of the Richard Hughes novel A High Wind in Jamaica, for about 40 years, but it wasn’t until the past week that I read it.

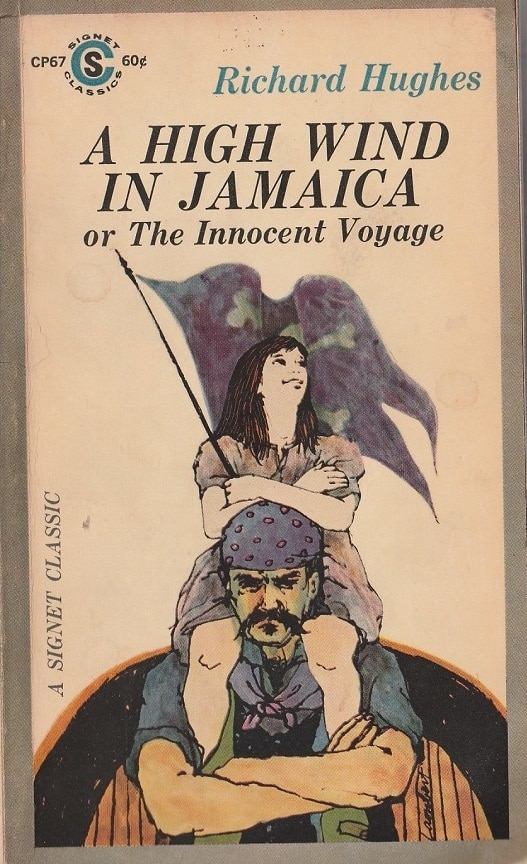

The book, originally called The Innocent Voyage, was published in 1929, but my paperback isn’t that old. It was printed, as best I can tell, in 1961, and, on its cover, it features a rather dour looking pirate with a smiling, cross-armed young girl on his shoulders, very much an image that recalls the “family” movies of the 1950s in which all children were cute and all stories were heart-warming.

About halfway through my reading, this copy fell apart in my hands, with a broken spine and loose pages. Luckily, I was able to quickly replace it with a new copy of the 1999 edition from New York Review Books, featuring, on its cover, a detail from the work “Storm brewing” by Chicago outsider artist Henry Darger.

This image shows several little girls, dressed in short skirts, fleeing with over-the-shoulder looks a dark storm of black, brown and gray that takes up the top half of the work. Like much of Darger’s art, there is a strangeness to this image, emphasizing the bare legs, arms and faces of the girls and their vulnerability and suggesting a danger greater than simply getting wet.

As it is, the illustration is creepy, but it’s even creepier if you know that Darger’s obsessively created manuscripts and collections include many images of young nude girls, sometimes undergoing violence and death.

In its creepiness, “Storm brewing” is a much more apt image for the cover of the Hughes novel than that “cute” kid one from 1961.

From Emily’s point of view

Not that A High Wind in Jamaica is creepy, exactly. “Creepy” suggests a sort of in-your-face nastiness. The novel, though, has something of an inverse creepiness.

Its narrator’s voice seems to relate the story with, almost, innocence, as if he — it’s clearly an adult male doing the telling — may not completely understand all its implications. In this sense, the novel’s original title The Innocent Voyage has an in-built ironic twist. That, I suspect, was quickly thought to be overly subtle. One can imagine adults picking up The Innocent Voyage, expecting to find a “wholesome” tale and discovering something much different.

A High Wind in Jamaica, as a title, has the benefit of not communicating much of anything. It is based on the fact that the trip of a bunch of European children to England on board the ship Clorinda during which much of the novel’s action takes place is precipitated by a hurricane — a “high wind” — that devastates the Jamaican landscape and the daily living on the island.

Of course, the tone of the book may not be due to the narrator’s dopiness, but to his insistence in telling his story from the point of view and knowledge of ten-year-old Emily Thornton and, to a lesser extent, of her four siblings: John, Edward, Rachel, and Laura.

Accompanying the Thorntons are two Creole children, Margaret and Harry Fernandez. At 13, Margaret has crossed the line from childhood into, at least, an early version of adulthood, and the narrator gives no voice to her thoughts. Instead, her actions speak for her.

Unwanted passengers

The mental lives of Emily and the other Thornton children is rooted very much in what is a still fantasy sense of reality. It is worth noting that none of them has reached puberty. By contrast, Margaret has, or, at least, it seems that’s true, based on what she does.

John is the oldest Thornton, probably 11, but, even from the beginning, he seems a weaker personality to Emily. She is clearly the strongest among the children.

This story takes place sometime before 1860. And the pirates who host the children are participants in a business that is no longer profitable. They aren’t exactly bloodthirsty. Indeed, some of them — called the Fairies — dress up as women to lull the sailors on the Clorinda into letting them board. It’s a clever stratagem, but the pirates get a little too clever.

They take the children to their ship in an effort to convince the Clorinda captain to hand over his money. He does so, probably more to save his own skin, but, about the children, he gets confused and thinks the pirates have murdered them, and, so, he sails away in the dark.

The pirates awaken to find they have the children now as unwanted passengers.

“Drew the line”

They’re a decent sort of pirates and put up with the kids, seemingly out of some innate or vestigial goodness. When the pirates board another ship in search of booty, they try to get the crew to tell them where the valuables are hidden:

Most of them, indeed, appeared frightened enough to have sold their grandmothers; but some of them simply laughed at the pirates’ bogey-bogey business, guessing they drew the line at murder in cold blood, sober.

Which, of course, indicates that the pirates also gave the impression that murder in cold blood is something they might do if they’d had a lot to drink.

There were probably other reason they put up with the kids — their entertainment value, for one, and their strangeness, for another.

“Fit of shyness”

Indeed, when it is discovered that the children’s ship has disappeared overnight, the sailors and the children aren’t sure how to deal with each other. The novel’s narrator explains that, at the post-boarding meal, “both parties were seized by a sudden, overpowering, and most unexpected fit of shyness.”

Only the captain and first mate are English-speakers and able to communicate with the youngsters:

The Spanish sailors, used enough to this difficulty, grinned, pointed, and bobbed; but the children retired into a display of good manners which it would certainly have surprised their parents to see.

Whereon the sailors became equally formal; and one poor monkeyfied little fellow who by nature belched continually was so be-nudged and be-winked by his companions, and so covered in confusion of his own accord, that presently he went away to eat by himself. Even then, so silent was this revel, he could still be heard faintly belching, half the ship’s length away.

A lark

Even so, with the resilience of childhood, Emily and the others quickly and simply accept their presence on the pirate ship as just another strange turn in their lives.

They treat it as a lark.

The pirates, though, know it isn’t. And so does the reader.

When an odd, unexpected and even violent thing happens, the children deal with it by inserting it into a fantasy logic.

In part, this is due to the extreme youth of some of the children. Three-year-old Laura, for instance, has an interior reality that is “something vast, complicated, and nebulous that can hardly be put into language.” Because she is nearly four, she is, the narrator explains, certainly a child “and children are human (if one allows the term ‘human’ a wide sense).”

But she had not altogether ceased to be a baby; and babies of course are not human — they are animals, and have a very ancient and ramified culture, as cats have, and fishes, and even snakes; the same in kind as these, but much more complicated and vivid, since babies are, after all, one of the most developed species of the lower vertebrates.

“Had ever existed”

This is an example of the humor in A High Wind in Jamaica, delightful but also unsettling. Laura’s experience of the pirates and the pirate ship is deeply rooted into the fantasy that she, as a child or as a baby, has developed in order to understand reality. It’s not really real.

At ten, Emily is much better able to integrate the realness of her experiences into her own mental framework — but not completely. Fantasy still comes into play.

For instance, when an important character dies, Emily and the other children simply disregard it — won’t think about it:

Neither then nor thereafter was his name ever mentioned by anybody; and if you had known the children intimately you would never have guessed from them that he had ever existed.

Later, events of a sexual nature take place, some of which confuse Emily and others of which she doesn’t even notice.

This is, of course, a kind of protective avoidance for her and the other children. They are able to hold tight to a blissful refusal to see or understand what they are going through and refuse to have much to do with Margaret who sees and understands.

Delightful and troubling

A High Wind in Jamaica is a one-of-a-kind novel in which the reader views several months of events that carry threat and trauma and deep psychic damage from the point of view of children while also being aware of what the children aren’t seeing and understanding.

It is filled with humor edged in danger, delightful and troubling always.

It is not an innocent voyage.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.26.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.