I’m of two minds about Colin Woodard’s 2011 American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America.

On the one hand, it provides an interesting and, I think, generally useful framework with which to view the history of the North American continent, particularly the development of the European colonies on the East Coast as they evolved, in a fractured way, into the United States.

On the other hand, I’m not sure that Woodard’s designations are all that handy in attempting to understand U.S. history in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

The map

In his introduction, Woodard notes that American Nations has some similarities to but is also very different from Joel Garreau’s 1981 book The Nine Nations of North America. That book was “a snapshot in time, not an exploration of the past,” whereas Woodard starts his narrative in 1560 and carries it into the 21st century, an arc of more than 450 years.

Woodard has a much greater debt to a host of other scholars, especially those frequently cited in his notes:

- Alan Taylor (American Colonies. The Settlement of North America to 1800, published in 2001),

- David Hackett Fischer (Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America, in 1989, and several others),

- Kevin Phillips (The Emerging Republican Majority, in 1969; The Cousins’ Wars: Religion, Politics and the Triumph of Anglo-America, in 1999; and several others).

What Woodard has done is to take this earlier work and synthesize it into his own way of viewing North America and its history — a way that assigns each area of the U.S., Canada and northern Mexico into one of eleven cultural nations.

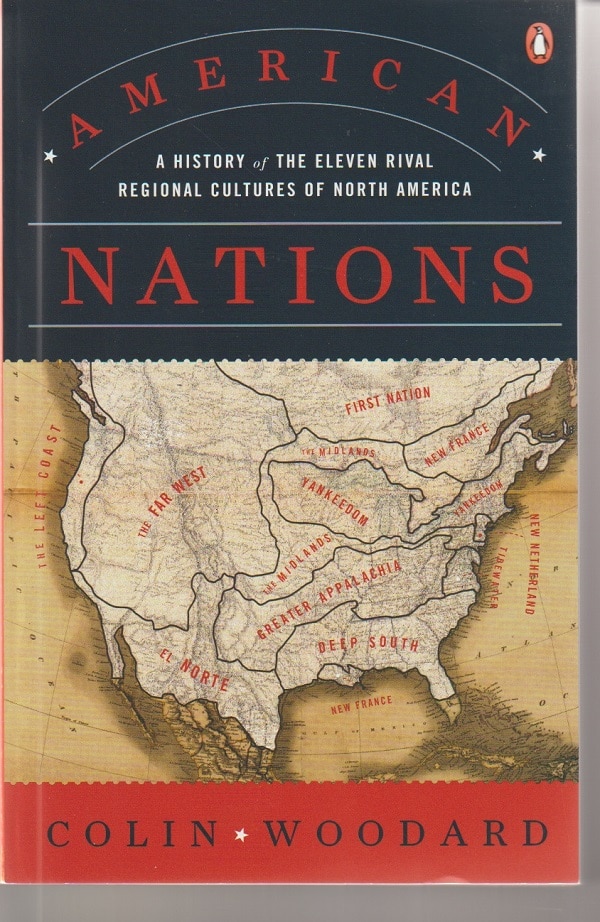

Here’s a map from the book’s cover:

The Nations

And here are descriptions of each nation, as spelled out in a nine-page section in the introduction:

- Yankeedom: “A culture that put great emphasis on education, local political control, and the pursuit of the ‘greater good’ of the community, even if it required individual self-denial.” (Think New England.)

- New Netherland: “A global commercial trading society: multi-ethnic, multi-religious, speculative, materialistic, mercantile and free trading…[with] a profound tolerance of diversity and an unflinching commitment to the freedom of inquiry.” (Think New York City.)

- The Midlands: “Arguably the most ‘American’ of the nations…Founded by English Quakers, who welcomed people of many nations and creeds to their utopian colonies…Pluralistic and organized around the middle class, the Midlands spawned the culture of Middle America and the Heartland, where…political opinion has been moderate, even apathetic.” (Think, as Woodard says, Middle America.)

- Tidewater: “The most powerful nation during the colonial period and the Early Republic, has always been a fundamentally conservative region, with a high value placed on respect for authority and tradition and very little on equality or public participation in politics.” (Think Revolutionary Virginia.)

- Greater Appalachia: “Founded in the early eighteenth century by wave upon wave of rough, bellicose settles from the war-ravaged borderlands of Northern Ireland, northern England, and the Scottish lowlands…Intensely suspicious of aristocrats and social reformers alike…Combative culture.” (Think, as Woodard writes, “bluegrass and country music, stock car racing, and Evangelical fundamentalism.”)

- Deep South: “Founded by Barbados slave lords as a West Indies-style slave society…The Bastion of white supremacy, aristocratic privilege, and a version of classical Republicanism modeled on the slave states of the ancient world, where democracy was a privilege of the few and enslavement the natural lot of many.” (Think Dixie.)

- New France: “A nation-state-in-waiting in the form of the Province of Quebec…Down-to-earth, egalitarian, and consensus-driven…The most liberal people on the continent.” (Think Quebec and New Orleans.)

- El Norte: “Oldest of the Euro-American nations…A place apart, where Hispanic language, culture, and societal norms dominate…Both sides of the United States-Mexico boundary are really part of the same norteno culture.” (Think El Paso and Juarez.)

- The Left Coast: “A Chile-shaped nation pinned between the Pacific and the Cascade and Coast mountain ranges…Combines Yankee faith in good government and social reform with a commitment to individual self-exploration and discovery.” (Think California.)

- Far West: “The colonization of much of the region was facilitated and directed by large corporations headquartered in distant [cities] or by the federal government…The region remains in a state of semi-dependency. Its political class tends to revile the federal government for interfering in its affairs…while demanding it to continue to receive federal largess.” (Think, as Woodard writes, “high, dry and remote.”)

- First Nation: “A vast region with a hostile climate….Its indigenous inhabitants…still retain cultural practices and knowledge that allow them to survive in the region on its own terms.” (Think northern Canada.)

A federation

That’s a long list, and it’s a lot to try to keep in mind while reading American Nations although Woodard certainly works hard to remind the readers who the people are who, at a given historical moment, make up, say, Greater Appalachia or the Midlands.

Americans are not used to thinking in this way. We tend to see state borders or geographical regions. Yet, as Woodard’s map shows, his cultural groupings aren’t hemmed in by state or even national lines. He writes:

America’s most essential and abiding divisions are not between red state and blue states, conservatives and liberals, capital and labor, blacks and whites, the faithful and the secular.

Rather, our divisions stem from this fact: the United States is a federation comprised of the whole or part of eleven regional nations, some of which truly do not see eye to eye with one another.

He notes that cultural geographers, such as Wilbur Zelinsky, have found that, when an empty territory is first settled, “the specific characteristics of the first group able to effect a viable, self-perpetuating society are of crucial significance for the later social and cultural geography of the area.” For instance, the Dutch may be long gone from New York but their legacy of commercial gusto, openness to diversity and a refusal to be limited by traditions remains.

And, Woodard argues, that cultural identity tied to a location is only getting stronger today since, over the past half century,

Americans have been relocating to communities where people share their values and worldview…As Americans sort themselves into like-minded communities, they’re also sorting themselves into like-minded nations.

Seven of eleven nations

If you look at Woodard’s map, you’ll see that not all of the continental United States. is in one of these 11 nations. The southern tip of Florida, dominated by Cubans, relates more to the Spanish Caribbean than to any other U.S. cultural group. I liked his willingness to recognize that, in one piece of American land, the culture is looking outward in this way.

I also liked his willingness to recognize how the northern part of Mexico and the U.S. land along the border are the same cultural group, as are the people of the Quebec area and New Orleans.

I liked how all of Canada is covered in his groupings — the U.S. and Canadian parts of the Far West, and the Left Coast, and the Midlands. And I liked that he recognized the indigenous people in northern Canada as a cultural grouping of their own, and one that could have more of an impact in the future.

In all of this, Woodard is, to some extent, following Garreau’s map.

The bulk of Woodard’s book, however, doesn’t have much to say about El Norte, New France, the Far West and the First Nation, each of which has existed somewhat separate in cultural bubbles. The Far West, he explains, has been a kind of stepchild of national corporations and the federal government, more acted upon than acting. As for El Norte, it’s isolation is now starting to change, as it is seen as a focus of attention from the other nations and also as a key voting bloc.

Most of the pages in American Nations deal with the interactions of seven of the eleven nations: Yankeedom, New Netherland, the Midlands, Greater Appalachia, Tidewater, Deep South and, later in U.S. history, the Left Coast.

Four confederations?

The best chapters of American Nations are those which deal with the Revolution, the Civil War and the westward movement of the individual or groups of nations. In such sections, Woodard is able to detail the usually temporary alliances among the cultural groups in an effort to take control of the situation or block others from doing so.

For instance, the expansion west, as Woodard explains it, was a complex set of cultural group movements:

The first half of the nineteenth century saw a four-way competition for control of the western two-thirds of North America, with Yankeedom, the Midlands, Appalachia, and the Deep South extending their cultures over discrete swaths of the Trans-Appalachian West. At stake, all parties knew, was control of the federal government. Whoever won the largest parcel of territory might hope to dominate the others, defining the norms of social, economic, and political behavior for the rest…

But by midcentury this demographic and diplomatic struggle was becoming a violent conflict between the continent’s two emerging super-powers: Yankeedom and the Deep South, far and away the wealthiest and most nationally self-aware of the four contestants. Neither could abide living in an empire run on the other’s terms.

The result didn’t have to be the Civil War, according to Woodard. Instead, if the hot-heads in South Carolina hadn’t acted precipitously, the United States — he theorizes — would have

split up into four confederations in 1861, with dramatic consequences for world history. But hostilities could not be avoided, and the unstable union would be held together by force of arms.

Less convincing

Much of the first half of American Nations was, I found, a fresh and interesting look at U.S. history from Woodard’s perspective.

Once his book got to the last 100 years or so, it seemed to me to be less convincing.

For one thing, Woodard has no place for an African American nation. Yet, since 1950, the civil rights movement and the societal changes that it has sparked — not only for African Americans but also for women, the disabled, the LGBTQ community — has been one of the strongest political and social forces in the nation.

Consider the last presidential election: It was the African American vote that was the bedrock of the slim majority that brought victory to Joe Biden in Georgia. And, two months later, brought razor-thin majorities for two Democratic senatorial candidates in that state, giving the party control of both chambers of Congress.

For another, if you look at his map, Woodard has Wisconsin and Michigan as part of Yankeedom, but, four years ago, the voters there gave their votes — and the White House — to Donald Trump.

By the time he gets to the 20th century, Woodard is writing about two “superpower” national blocs — one centered on Yankeedom and the other on the Deep South. This sounds a lot like the way we often think about policy wars, as a battle between the North and the South.

I’m not sure Woodard’s attempt to sharply define and contain these groups works as we near our present time.

No “American” identity

Nonetheless, I think he’s right when, near the end of his book, he argues:

It is fruitless to search for the characteristics of an “American” identity, because each nation has its own notion of what being American should mean.

This, I think, is the ultimate benefit of American Nations. Woodard shows very clearly that the cultural groups that rose up on the North American continent over the past two hundred or so years never have agreed about what it means to be American.

At times in Woodard’s book, I got confused about who were the people from, say, The Midlands and those from Greater Appalachia. But I was never confused about this key point — that there is a great disagreement about how strong or weak government should be, how helpful or distant it should be, what ideals the United States should stand for, and much more.

And, certainly, that should be clear after the past four years of the Trump presidency.

His base — whatever place they have in Woodard’s cultural groupings — have a vision of the United States that is radically different from that of a large group of Americans. You can call those Americans Yankees or Left Coasters or whatever, but their vision — Bidenism? — is antithetical in many ways to the vision of Trumpism.

Maybe that’s the best help going forward, to recognize that we really, really don’t agree. I hope that there can be issues on which some compromise is possible. But I will never be able to agree to the America that Trump loyalists want, and they’re not going to agree with mine.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.16.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

I gotta share something kinda tough from just last week. I got caught up in this investment scam, and man, I lost a big chunk, like 80 grand. It all started with those promises of making big bucks, but it ended up being a total mess of lies from these shady folks. But hey, here’s a little silver lining in the gloom. I stumbled upon this legit recovery services called SWIFT RECOVERY FIRM. They asked for solid proof that I’d been scammed, so I sent them all the docs I had. And you won’t believe it – they worked some magic and got my money back, like, real quick. So, if you’re stuck in the same boat, don’t give up. There’s still hope out there. Hit up sw*********************@***il.com and get back on the road to financial peace. Whatsapp them on +1 (786) 684-0501