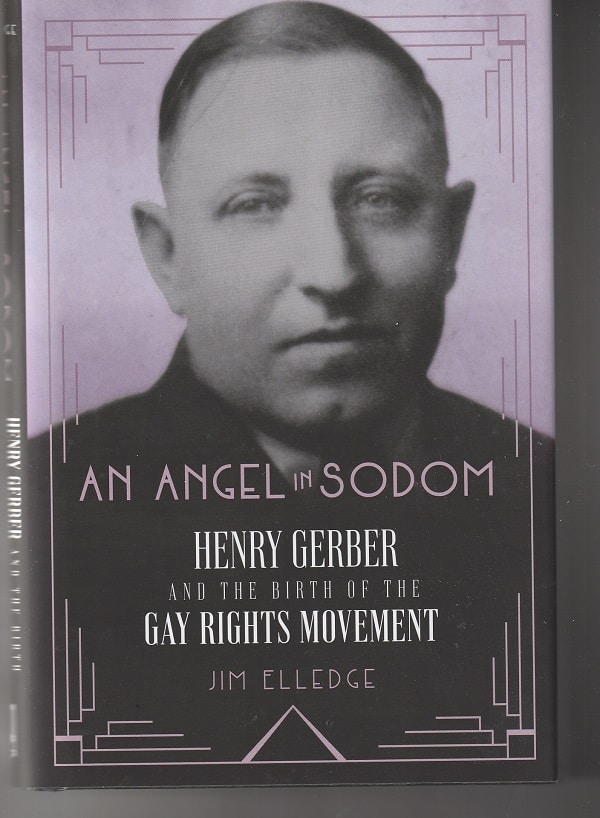

As a title, An Angel in Sodom is evocative and a bit ambiguous. The subtitle of Jim Elledge’s book is much more direct: Henry Gerber and the Birth of the Gay Rights Movement.

This is a biography of Gerber, a cantankerous visionary who attempted a century ago to go to bat for gay people like himself and for their rights. In Chicago in 1924, he founded the Society for Human Rights, the first homosexual rights organization in the U.S., complete with a charter from the state of Illinois, and the first homosexual rights publication in the nation, Friendship and Freedom.

Like many another trailblazer, the German-born Gerber saw his efforts quickly come to naught after a police raid in July, 1925, led to court troubles, the disbandment of the group and the discontinuation of the newsletter.

It was, at the time, an obscure moment in American gay history, only later recognized widely as a valiant if quixotic attempt to counter mainstream prejudice by taking a public pro-homosexual stand.

And not just recognized but honored by mid-20th century gay activists as an inspiration to their more successful flexing of political and social power.

Working in the shadows of his time

Near the end of his life, Gerber — who died in 1972 at the age of 80 — got involved a bit in the beginnings of a much broader, ultimately successful gay rights movement, but not for long. His deep-rooted crankiness left him unsatisfied with what the new generation of advocates were doing.

It seems from An Angel in Sodom that Gerber never fully realized the high regard that his name eventually won within the movement. Indeed, he has been called “Father of the Homophile Movement” and “father of homosexual liberation in America” and “Grandfather of the American Gay Movement.”

Yet, even with such accolades, it’s likely that there are many gay Americans today who have never heard of Gerber. His groundbreaking work began and ended in the shadows where, in that era, gay Americans had to operate.

An Angel in Sodom

Which is where the title of Elledge’s book comes in.

As a title, An Angel in Sodom suggests someone who was a ray of light in a dark place. A century ago, mainstream Americans demonized the gay culture as a kind of Sodom, a name out of the Bible for a place of wickedness, perversion and evil.

That was how the straight culture saw it, but, for Gerber and other gay people, it was simply living their lives as who they were.

Gerber wasn’t a saint in any religious sense. He hated organized religious. And he was no asexual celestial being. He spent his life looking for and finding and, often, paying for sexual encounters.

Gerber, however, is the one who initially came up with the title — not for Elledge’s book but for his own book of fiction that he was working on in the mid-1940s.

Lost

Gerber’s Angels in Sodom was, writes Elledge, a manuscript made up of “two thematically related novellas that he had written in German years earlier and then translated into English.”

The title of the manuscript comes from one of the novellas, Angels in Sodom, which “explored the experiences that a young Berliner, who was arrested and convicted for same-sex sexual activities, faced in prison.” The other novella was Boy Meets Boy, the story of a bisexual Parisian.

Elledge reports that this was one of five books that Gerber had written by the time:

In Moral Delusions, he traced the development of laws against homosexuality from their beginnings in the Old Testament and revealed how different they were from one state to another. In his other books, he focused on Christianity and advocated atheism; explored ethics, as applied to politics; and surveyed his lifelong “struggle to do something for the cause.”

That is all we know about the books.

These manuscripts which would have provided a wealth of insights into Gerber and his thinking and his motivations are lost.

“Henry’s epistles to the perverts”

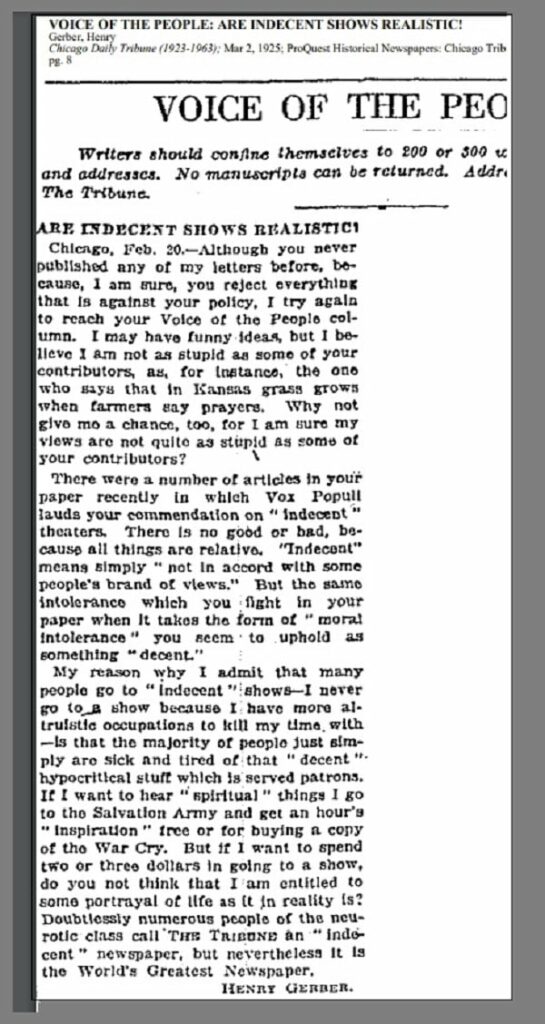

Virtually all of Gerber’s personal papers are lost as well. So, too, the records of his Society for Human Rights and its Friendship and Freedom publication, all confiscated and destroyed by government investigators.

For decades, even after Gerber was rediscovered by gay activists more than half a century ago, anyone wanting to know anything about the trailblazer had to piece together bits of information, often conflicting, from here and there. The main source was a seven-page recollection that Gerber wrote in 1962 for ONE Magazine, “The Society for Human Rights: 1925.”

That magazine was published by ONE, Inc., a national gay rights organization which, in 1956, established the ONE Institute, an academic body for the study of homosexuality. This later led to the creation of the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries, the oldest existing lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) organization in the United States and one of the largest repositories of LGBT materials in the world.

It was when Elledge was at the archives in Los Angeles several years ago that he discovered “a treasure trove of Gerber and Gerber-related materials, specifically his, Frank McCourt’s, and Manuel boyFrank’s exchange of letter, what boyFrank dubbed ‘Henry’s epistles to the perverts.’ ”

As that brash and puckishly impertinent comments suggests, the correspondence among the three gay men could be playful, but it was also, at times, testy.

The main subject in all of the dozens of letters — McCourt was a photographer, and boyFrank served in the armed forces with stints in the Army, Navy, and Coast Guard — was how to live a gay life in an anti-gay America. And boyFrank went out of his way to ask Gerber for details about his early and later efforts to oppose discrimination against homosexuals, promising to save the letters.

Lucky for Elledge and now for Elledge’s readers that he did.

A window into gay life

One of the delights of An Angel in Sodom is how these letters and a lot of other research that Elledge brings to bear provide a window into the lives of gay men throughout the first half of the 20th century.

Yes, there are their debates about how to counter prejudice as a public policy, but there are also many discussions of how to find romantic partners and how to avoid getting in legal trouble while doing that.

The treasure trove of letters that Elledge found is rich, but it also isn’t enough to give as full a picture of Gerber as the man deserves.

Gerber was an unusual character, an immigrant from Germany who somehow had the audacity to assert the legitimacy — and the naturalness — of the gay life in a close-minded America, puritanical and looking for scapegoats.

Elledge does a good job to mine the letters and Gerber’s relatively extensive writings to get at his motivations and influences, particularly post-World War I Germany. But — through no fault of Elledge — there is much still that remains in the shadows.

Was Gerber simply one of those prickly people whose ego was so large that he was undaunted by the opposition of an entire mainstream culture? Was there something in his upbringing that pushed him to work against the unfairness of the anti-gay discrimination?

Did he have one or more models of such fights in the past? Did he, for instance, know and relate to Mahatma Gandhi’s work against British colonialism in India? Or perhaps the founders of the United States? What made Gerber tick?

Elledge provides many details, and, unless some other great source of information turns up, this book is the best we have to go on. And it’s a great improvement over what was available before Elledge started his research.

“Mutual love”

The greatest insight into Gerber that Elledge provides has to do with romance.

Gerber spent his life looking for gay sex, often having to pay for it, but, as important as the physical experience was, there was something else driving him. As Gerber wrote in one of his letters to boyFrank:

There is nothing more beautiful than mutual love, naked in bed, with kissing and embracing the other person. With me it does not matter ‘how one goes off,’ the main thing is the embrace and kiss.

Elledge presents that quote, and then adds: “Unfortunately, he never found anyone who suited him and who returned his interest.”

It’s a sad commentary for someone who worked so hard and for so long — and with little success — so that every gay man could find the love of his life.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.18.22

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 10.4.22.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.