Some writers have a huge hunger to write and publish. Others, it seems, don’t.

For instance, Evan Hunter, who started life as Salvatore Lombino and employed several pseudonyms, started his book writing career in 1952 and, over the next 53 years, published 119 novels. Nearly half of them (51 novels and four novellas) came out under the name of Ed McBain and had to do with the police detectives of the 87th Precinct in a city very much like New York.

By contrast, Clair Huffaker published just eleven novels in a writing career that lasted 19 years — or one novel for every ten that Hunter wrote in his half-century of writing.

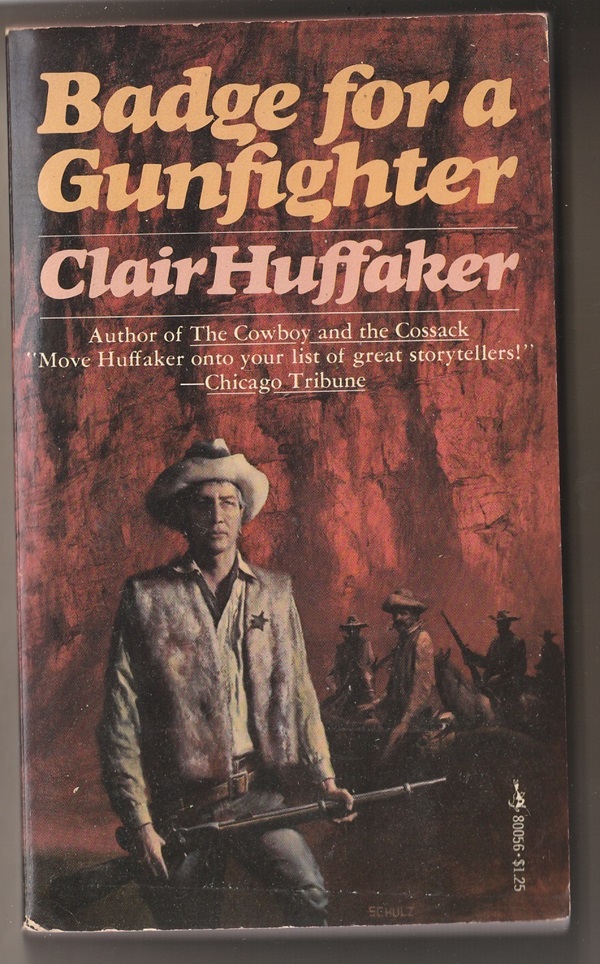

Huffaker was born in Magna, Utah, on September 26, 1926, three weeks before Hunter came into the world in East Harlem in Manhattan. Yet, by the start of 1957, when Huffaker brought out his first novel Badge for a Gunfighter, Hunter had already fourteen novels to his name. They were both then 30.

Both had served in the Navy in World War II. Afterwards, Hunter came back to New York where he quickly focused on a career in writing. Huffaker, who had attended Princeton and Columbia Universities as well as the Sorbonne in Paris, ended up in Chicago after the war, working as an assistant editor for Time.

Huffaker’s eleven novels

Once he turned his hand to fiction, Huffaker was a success, publishing novels, mostly westerns, and had a second career as a Hollywood scriptwriter, cranking out scripts for thirteen films released between 1960 and 1973, six of which were based on his novels.

Here’s a list of Huffaker’s novels:

- Badge for a Gunfighter (January 1, 1957).

- Badman (April 1, 1957), also sold as The War Wagon, filmed as The War Wagon.

- Rider from Thunder Mountain (November 1, 1957), also sold as Guns of Thunder Mountain and as Thunder Mountain.

- Cowboy (1958), novelization of the screenplay.

- Flaming Lance (1958), also sold as Flaming Star, filmed as Flaming Star.

- Posse from Hell (1958), filmed as Posse from Hell.

- Guns of Rio Conchos (1958), filmed as Rio Conchos.

- Seven Ways from Sundown (1959), filmed as Seven Ways from Sundown.

- Good Lord, You’re Upside Down! (1963).

- Nobody Loves a Drunken Indian (1967), also sold as Flap, filmed as Flap.

- The Cowboy and the Cossack (1973).

In addition to those books and his movie scripts, Huffaker wrote two non-fiction books: One Time I Saw Morning Come Home (1974), a recollection of his childhood, and Clair Huffaker’s Profiles of the American West (1976), a gathering of stories from the history of the West.

What might have been

I mention all of this because, from the first, Huffaker was an inventive, highly entertaining and engaging storyteller.

His life can be divided into three parts: his youth and early adult years during which he published no books, his midlife from 30 to 50 when all his books and movies were created, and his later life from 50 to his death from an aneurysm at 63 when he didn’t publish anything.

Given his relatively young age at death, I have the thought that Huffaker might have had bad health. Or maybe he had a troubled life. He was married five times, according to the Internet Movie Database, the last time to prominent Texas attorney Norma Lee Fink. He was buried in Westwood Memorial Park in L.A., in the same grave that Fink, who died in 2006, now shares.

I’ve read seven of his eleven novels, including, just recently, that first one Badge for a Gunfighter, and I’m left wondering what might have been. What might have been if he’d had the urge to write more books? What might have been if he had used the western as a subject for books of high literary ambitions, such as the work of Glendon Swarthout, Willa Cather, Leif Enger and Elmore Leonard?

Or what might have been if he had branched out from westerns? If, like Hunter, he had broken away from genre writing, at times, to author more literary novels. (In fact, Hunter employed his Hunter byline for his more serious works and used McBain and the other pseudonyms for crime novels.)

“They killed him”

In Badge for a Gunfighter, Huffaker showed what he could do. And it was a lot.

In Badge for a Gunfighter, Huffaker showed what he could do. And it was a lot.

Consider the opening sentences, taut and direct, hooking the reader right from the start:

They killed him in Spangle Valley. They waited hidden among the rocks on Buffaloback Mountain and when he rode below they shot him out of the saddle.

The killers work for Whitey Hall, “the biggest man in Yellowrock” — and the most corrupt. Their victim is a guy named Sullivan who was coming to be the town’s sheriff. Hall wanted to make sure the town didn’t have a sheriff, at least, not one that he didn’t control.

That’s why Cash Jefferson, a hired gunman, comes to Yellowrock — to be a sheriff Whitey can control. Although born Bruce Jefferson, Cash has gotten his nickname for his focus on getting paid for doing someone else’s dirty work.

And the money Whitey is paying is top-notch. All Cash has to do is pretend to be a real lawman and keep his connection to Hall secret.

“He knew he was dyin’”

That’s the set-up, a bit unusual for a genre western, but Huffaker goes much further in twisting the usual formula out of shape.

The guy who’s gunned down, for instance, Sullivan — in most westerns, he’d disappear from the pages of the story immediately after that opening. He’s dead, right? What’s more to say?

Well, Huffaker finds a way to bring him into the story in flashbacks to the moments between the time he was shot and the time he died.

The first occurs when Sullivan’s body is brought into the stagecoach station and the blacksmith who does some doctoring takes a look at him:

“He ain’t bleedin’, his heart ain’t beatin’, and he ain’t breathin’. He’s plain dead.”

From the corner comes a sob from Hank Brendan, a nine-year-old boy. Someone asks if he’s related to the dead man.

“No, I found him. I was fishin’ in the creek and heard the shootin’ and went up and found him.” He wiped his eyes with the back of his hand and stared down at his scuffed brogans. “He knew he was dyin’, and he was worried about how I’d feel havin’ him die on my hands. He was talkin’ normal, and I was tryin’ to talk some life into him but I couldn’t think of the right things to say.”

“Let himself die”

Whitey orders Cash to kill Hank because maybe, just maybe, Sullivan said something to him to reveal the deal he has with Cash.

For a genre western, this is pretty cold. Whitey is shown to be not just a bad man but an evil man. In all the westerns ever written, I wouldn’t be surprised if this is the first and only to involve an order to kill a kid.

Cash, at this point, seems to be willing to carry out the order, but his better nature gets in the way and, instead of shooting Hank, he shoots a rattlesnake that was about to bite the boy’s mother, Virigina. (Their eventual relationship, part of the usual formula, is handled by Huffaker with more subtlety than is usual in a western.)

As a thank-you for saving his mother, Hank gives Cash Sullivan’s badge:

“It’s a real badge. Mr. Sullivan gave it to me.

“He could see that I was — takin’ it hard, him hit so bad and all. He was tryin’ to smooth it over, make it easy on me cause I’m only a kid. I’d put my straw hat down to shade his eyes, and he said that was a mighty fine hat and he’d trade me his badge and his horse for it. Then, after a while, when he was sure the men who’d shot him wouldn’t come back and hurt me, he — let himself die.”

There is something wonderfully touching about this scene, and Hank’s description of it.

Bright and brisk

Badge for a Gunfighter is only 143 pages, but, on virtually every one of them, Huffaker is creating a real story, not just a repeat of thousands of earlier westerns following the formula.

In the final “shoot-out” at the end of the book, the genre formula is twisted out of shape as Huffaker has his hero employing such unusual weapons as a spur, barbed wire and a loud, piercing shriek.

Badge for a Gunfighter is refreshingly bright and brisk in its storytelling as are all of Huffaker’s other novels.

It’s just too bad there weren’t more.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.2.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.