“Visceral” is one of those no-nonsense words. It goes right to the gut.

You can look at art, look at the world, with your intellect. But, if you turn a visceral eye, you are short-circuiting reason and operating on instinct. This is about emotions. It is gritty as soil. It lacks the right-angles of logic.

The intellect and instinct can communicate, negotiate. No one operates with only one of these two approaches. Tension is constant. The intellect tamps down the instinctual. The visceral floods messily beyond the lines and categories of the mind.

Think of England’s Elizabeth I bragging, in the face of the Armada, that she had “the heart and stomach of a king.”

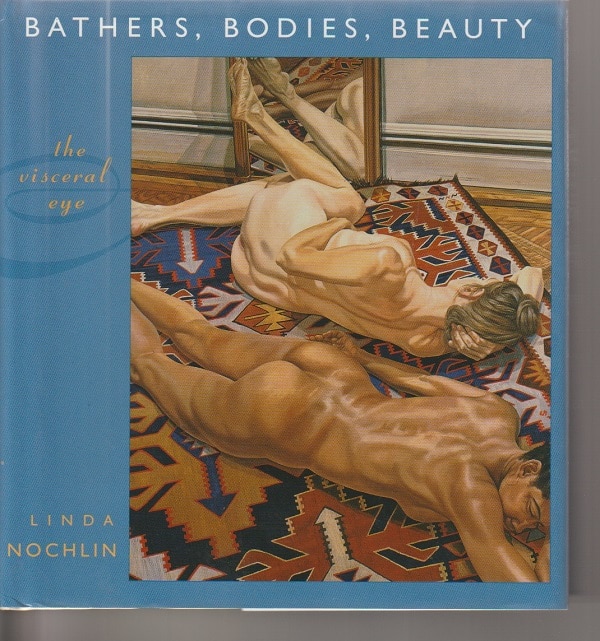

In Bathers, Bodies, Beauty: The Visceral Eye, noted art historian Linda Nochlin is a set of eyes and a body reacting to, responding to, dancing with centuries of paintings and other artworks. And an intellect.

The art with which her eyes and body engage has to do with the body, the most visceral of subjects — with bathing and swimming and water and the fear of water and the fear of (among men) castration and the way the body really looks (at least, to realist artists) and old age and decrepitude and death. Nothing more visceral than death.

“Sentimentalized, sexualized prettiness”

Consider Renoir’s The Great Bathers (1884-1887), the work with which Nochlin kicks off her 2006 book.

Nochlin first engaged with the painting a quarter century earlier, and, for her, it was a prime example of art created for the male gaze — created by and for men to enjoy, created to titillate male fantasies —

the paradigm of all I found wrong with the traditional representation of the nude. I found the painting…pernicious both from a formal standpoint and in terms of what it represented.

My negative gut reaction to the sentimentalized, sexualized prettiness of the image, I might add, was shared by many critics at the time Renoir painted it…

Pliant, seductive, natural, Renoir’s bathers embody a whole tradition of masculine mastery and feminine display which underpins so much of Western pictorial culture — and which was increasingly being challenged by feminists, social reformers, and the effects of the modernization Renoir increasingly despised.

“Simply breathing deeply”

Even so, Nochlin writes that something else was also going on for her. Even with her negative gut reaction, she was aware of another feeling —

a certain ambivalence, a certain undertow of attraction….

Perhaps Renoir’s nudes enable a certain feminine fantasy as well as the more conventional male one, a fantasy of bodily liberation.

It is difficult to imagine how [19th century] women, especially ample women, condemned to the strictures of corsets and lacing, must have felt before this vision of freely expanding flesh, the pictorial possibility of unconstricted movement, of simply breathing deeply, of not having their breasts pushed up under their chins and their ribs and lungs encased in whalebone.

In other words, a different sort of fantasy for a different gaze, the female gaze.

In this case, with this artwork, as with others in Bathers, Bodies, Beauty: The Visceral Eye, Nochlin is examining her own visceral reaction as well as the visceral reaction of art patrons — the men and the women.

“Whale-women”

Nochlin has an even stronger reaction to another Renoir canvass, considered by many a masterpiece, The Bathers (1918), created more than three decades after The Great Bathers:

The beached, blubbery whale-women in Renoir’s The Bathers of 1918 are of course, without question, antifeminist icons, an insult to the feminine mind and body.

Even so…

Even so, even as she describes these two women and “their rolls of fat (perhaps an inspiration for the Michelin Man),” Nochlin recognizes that there is another way for “I, and you” to look at and take in this painting.

One might say that, in his old age, Renoir finally allowed himself to go literally over the top: over the top of Impressionistic visual verism, over the top of the kitschy classicism of The Great Bathers, into a visceral dreamland…The nude has expanded, liquefied, deboned itself into a viscero-visionary icon of pneumatic bliss.

“Anesthetized gunk”

This work, painted by Renoir in his 70s near the end of his life, exhibits what might be called “an old age style, whatever we mean by this suspect term,” and Nochlin writes:

These nudes lie down for the most part, succumbing to the downward pull of the flesh, to gravity, and the better to demonstrate the enticing abjection of the flesh. Yet even if they maintain their status as “nudes,” their flesh has been transmuted by a kind of reverse alchemy into some lower substance, a sort of anesthetized gunk.

Nochlin writes that, in their “antihumanism,” the figures in this painting presage the “inventively macerated bodies” to come from Picasso, De Kooning and others.

In other words, I think what’s happening is that Nochlin is having a visceral reaction to Renoir’s own visceral reaction to the “feminists, social reformers, and the effects of the modernization Renoir increasingly despised.”

“Monster-woman”

Even more over the top, more visceral, is a 1934 drawing by Picasso of a man in a bathtub being murdered by a woman with a huge knife, titled Le Muetre (The Murder) and a variation on David’s painting of the Death of Marat, the French Revoluton leader stabbed and murdered in his bath by a woman.

This is a drawing that Nochlin writes “embodies gender antagonism at its most exacerbated.” The central figure “is the monster-woman with her hideous mouth-trap, phallic and castrating at the same time.” And she writes:

The primitive head in Le Meutre, token of unconscious fears and forces, is attached to curving signifiers of Western, middle-class, feminine domestic life — tablecloth, high-heeled shoe, tables, breasts. The female is a trap not just because she has a vagina dentata (primitive, unconscious) but also because she incarcerates the male — the hero, the artist — in a hideous web of bourgeois triviality.

“Visual bravado”

As Nochlin notes, it is unusual for a male to be portrayed in a painting in the bath. Usually, it is the female who, naked, is being observed in these intimate moments.

Yet, in several examples that she offers in her chapter on men and women in the bath, something not so voyeuristic is going on — or, maybe more correctly, also going on.

Nochlin writes that it’s tempting to think of Woman Bathing in a Shallow Tub as being based simply on perception, “keyhole vision.” But that doesn’t take into account “the heightened role of invention” in the work.

The bending bather and the “background” — the blue draperies, the transparent curtain and the oddly intrusive fragment of red chair, the carpet, the white bed linen to the right, the towel on the carpet, its angularity foiling the roundness of the tub — are not deployed “realistically” as they would be in some Academic-naturalist version of the same subject.

One can only think of Japanese prints, which Degas collected, in considering such visual bravado in confronting the intimate. Degas is making strange not just the woman’s body, not just the articulation of the piecemeal space that surrounds her, but the act of seeing itself.

After several pages spent discussing this work, Nochlin suggests that Degas’s loss of his mother in childhood may provide the key to decoding it.

I’m not sure if that’s helpful or necessary. It seems an attempt by the intellect to organize the viewer’s feelings about the work into some understandable package.

I trust much more Nochlin’s words for the work: “visual bravado.”

“Sitting for a portrait”

Nochlin considers dozens of art works in Bathers, Bodies, Beauty, but none with as much personal import as the 1968 portrait by Philip Pearlstein Portrait of Linda Nochlin and Richard Pommer.

The painting was commissioned as a wedding portrait, and we are both wearing the clothes we were married in, very sixties, very hip: Dick, white linen trousers and a blue shirt; Linda, white dress with a bold blue geometric pattern. We are represented sitting in Philip Pearlstein’s studio in Skowhegan, illuminated by the cold light of dentist’s lamps, sweating in the heat of a Maine summer.

I always find photographs of myself off-putting. It’s a visceral reaction, and I suspect this is true of many people. The camera clicks, and there I am. I know it’s me, but it’s not me. Those primitive tribes who felt the camera click took away the sitter’s soul may have been onto something.

The complexity of such feelings, though, it would seem to me, is even greater when the portrait has been created by a painter in a process while has taken a long and tedious time. Here’s what Nochlin says:

The painting engages a long process of creation and an afterlife of experience. Temporality is necessarily involved, whether in the seemingly endless and discomforting — at times even agonizing — sitting for a portrait or, equally important, in living and aging with it after its completion.

“Us, exactly”

What is that like? Did a Renoir model ever come back to look at the painting in which she appeared? Did she feel like a whale-woman? Did the woman in the tub who was painted by Degas ponder her rounded back and bent torso, especially later when bending that torso would have been much more difficult?

Nochlin reports:

In the beginning we thought we looked old; but a time came when we overtook the painting and looked back on it as a record of a moment when we were in fact quite young.

Even so, she adds:

There was never a time when we looked at it and said, “Ah, yes, that’s us, exactly.”

Nochlin’s book chronicles a restless and relentless and endless process of engaging with art — with what it means and how it feels.

A visceral act, with the visceral eye.

.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.18.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.