There is something very human about the Old Testament prophet Elijah whose name means “YHVH is my God.”

He is elusive like ruah (wind, spirit), writes Daniel C. Matt, an expert on Jewish spirituality, in the newly published Becoming Elijah: Prophet of Transformation from Yale University Press.

Indeed, Elijah is filled with ruah, sometimes to the point of obsession. “The spirit makes him zealous and stormy, unpredictable, restless. He is always on the move, his biblical roaming spanning the entire land of Israel….” He is also larger than life:

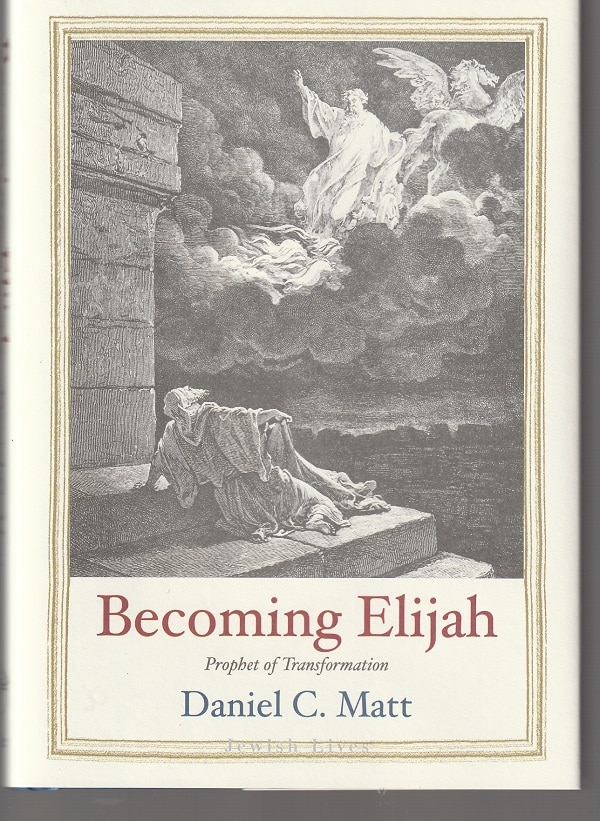

Elijah is fearless, fierce, and untamed — a hairy man, with a leather loincloth bound round his waist (2 Kings 1:8). The world, it seems, cannot bear him; finally, he is taken up to heaven in a chariot of fire.

In heaven, he becomes God’s herald. When the Messiah is to come, his imminent arrival will be announced by Elijah. In the meantime, though, he has other jobs to do.

As pictured by the rabbis debating the meaning and implications of the Scripture, Elijah rode his chariot to heaven and “turned into a unique angel.” Unlike other angels who rarely if ever leave paradise, Elijah “has a reason to leave, to move continually back and forth. He is on an endless mission: to rescue, teach, and inspire.”

Faster than the Angel of Death

Matt includes some wonderfully detailed speculations from rabbinic scholars, one of whom suggests that Elijah, as an angel, flies “through the world like a bird,” almost as effortlessly as Michael and Gabriel, the top two angels. Another writes:

“Michael [traverses the world, reaching his destination] in a single [glide, or stroke of his wings], Gabriel in two, Elijah in four, and the Angel of Death in eight.”

Not only has Elijah transcended human life by arriving in heaven still alive, but he also transcends his Jewish roots. “Beyond Judaism,” writes Matt, “his sway extends to its daughter faiths: Christianity and Islam.”

Matt’s Becoming Elijah is a lively, erudite and buoyant examination of the Elijah who has been an important religious figure for more than 2,500 years. Matt’s scholarship is deep, and his writing is nimble, entertaining and informative.

The book is short, just 156 pages of text plus another 38 pages of notes, yet it is as rich and meaty as a much longer work. After an introduction, Matt offers six chapters, and their titles give a sense of the breadth and depth of his book:

- I Have Been So Zealous for YHVH: Elijah in the Hebrew Bible

- The Compassionate Super-Rabbi: Elijah in the Talmud and Midrash

- Inspiring the Mystics: Elijah in the Kabbalah

- Elijah and the Daughters of Judaism

- Rituals of Anticipation

- Becoming Elijah

Elijah, Moses and Jesus

Matt notes in his discussion of Elijah’s importance to the “Daughters of Judaism,” that, in the New Testament and among early Christians, John the Baptist was thought to be Elijah.

He was described in Matthew 3:4 as wearing “a garment of camel’s hair with a leather loincloth around his waist.” And, in Matthew 17: 12-13, Jesus tells the disciples that Elijah has already come but wasn’t recognized, and, from this, they understand that he’s speaking about John the Baptist.

When Jesus goes up a mountain with three disciples to pray, he is transfigured with his garments “glistening, intensely white.” And Matt writes:

The disciples then saw Elijah and Moses appear, speaking with Jesus, and from the cloud there came a voice: This is My beloved Son; listen to him!” (Mark 9:7). The scene may be intended to demonstrate that Jesus is the fulfillment of the Torah (given to Moses) and the Prophets (represented by Elijah).

In Islam, Elijah shares many characteristics with al-Khidr, known also as the Green One, the Verdant One, a symbol of rebirth.

In Islamic legend, al-Khidr drank from the River of Life and, like Elijah, became immortal. He is pictured as the Eternal Youth, yet, like Elijah, he can appear in numerous guises, frequently as an old man. Both can manifest anywhere at any time to rescue those in crisis and extend compassion, before suddenly vanishing.

“Becomes gracious and generous”

The bulk of Becoming Elijah is devoted to the presence of the prophet in the mind and heart of Judaism. And a major point of discussion for Matt is how different Elijah is after he ascends into heaven on his chariot.

His arrival there isn’t the end of his story but the beginning of a new chapter in which the prophet evolves in terms of his character and personality. On earth, Elijah was “a zealous prophet of God…who parched the land with drought and slaughtered his pagan rivals.” Then, in heaven, as God’s messenger, he develops compassion.

[H]e returns to earth … frequently — to save those in danger, fight for justice, champion the innocent, heal the sick, gladden the miserable, fortify the weak, and stimulate both the wicked and the average to engage in teshuvah (“turning back” to God). He becomes gracious and generous, helping those in need and ultimately heralding salvation.

That’s quite an evolution. In fact, some of the rabbis who studied and thought about Elijah over the centuries believed that God was angry at Elijah’s life on earth for excessive zealotry.

“May fire come down”

This zealotry is repeated through the Hebrew Bible, but few of God’s human messengers are as bloodthirsty as Elijah. At one point, King Ahaziah sent a company of fifty soldiers to take him in, and the prophet told the captain of the troops,

“If I am a man of God, may fire come down from heaven and consume your company of fifty!” And fire came down from heaven and consumed him and his company of fifty (2 Kings 1:9-10)

The king sent another captain and fifty soldiers, and, again, Elijah brought down the fire of heaven to burn them up.

A third time, the king sent a captain and fifty soldiers, but, this time, the captain, aware of what had gone before, got on his knees and pleaded with Elijah for their lives. That still might not have been enough to save them from God’s fire, but “The angel of YHVH spoke to Elijah: ‘Go down with him. Do not fear him.”

“A sound of sheer stillness”

Eventually, the prophet moves beyond expressing God’s anger at the idolators who worship Baal and, acting in retaliation for the slaying of a just man, employs this fanaticism as

a champion of ethical demands, advocating for justice and human rights. He exhibits the moral conscience that develops further in the classical prophets of the next century: Amos, Hosea, Micah, and Isaiah.

Late in his career, Elijah is blessed — or maybe “bullied” is a better word — by God’s willingness to meet with him face to face. The prophet is hiding in a cave on Mount Horeb and God orders him to come outside, as Matt relates in his translation of 1 Kings 19-11-12, by way of Robert Alter:

Go out and stand on the mountain before YHVH. Look, YHVH is passing by, with a great and mighty wind tearing out mountains and shattering rocks before YHVH. Not in the wind is YHVH. And after the wind, an earthquake. Not in the earthquake is YHVH. And after the earthquake, fire. Not in the fire is YHVH. And after the fire, a sound of sheer stillness.

“Supernatural mediator”

This is one of the great moments in the Hebrew Bible — indeed, in all of religious literature. Yet, it comes just before God orders Elijah to find someone to take his place, Elisha. Matt notes that some rabbi commentators saw this as God being fed up with Elijah’s violence:

Elijah is so focused on God and on his own troubles that he has failed to plead for Israel or to respect them. He is no longer fit to be a prophet.

However, after his arrival in heaven, Elijah begins to express the depth of compassion that he often failed to exhibit on earth:

He becomes a supernatural mediator, bridging this world and the beyond. He delivers messages from above, reports the proceedings of the Divine Court, and transmits spirited debates from the Academy of Heaven. He knows that God is doing — and discloses this to worthy sages. To an inquiring rabbi on the road…he reveals God’s intimate feelings.

“Becoming Elijah”

In his final chapter “Becoming Elijah,” Matt notes that, in helping those still on earth, the prophet “cultivates kindness; his heart opens, and he discovers how to love.”

This is what those “turning toward God” can discover from Elijah, writes Matt. “As one learns to enact the prophet’s quality of compassion,” a person is “becoming Elijah.”

Matt writes that the story of Elijah is a two-act play — the first, the account in the Books of Kings, and, the second, a still unfolding revelation of a changed prophet:

In the global audience, each of us is a latent participant in the performance. Your own potential scene — your experience of Elijah — is unscripted, for he appears only by surprise.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.31.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.