The metaphor Thich Nhat Hanh uses to describe Buddha’s teaching is that of a raft. It is, he writes,

only a raft to help you cross the river, a finger pointing to the moon. Don’t mistake the finger for the moon. The raft is not the shore.

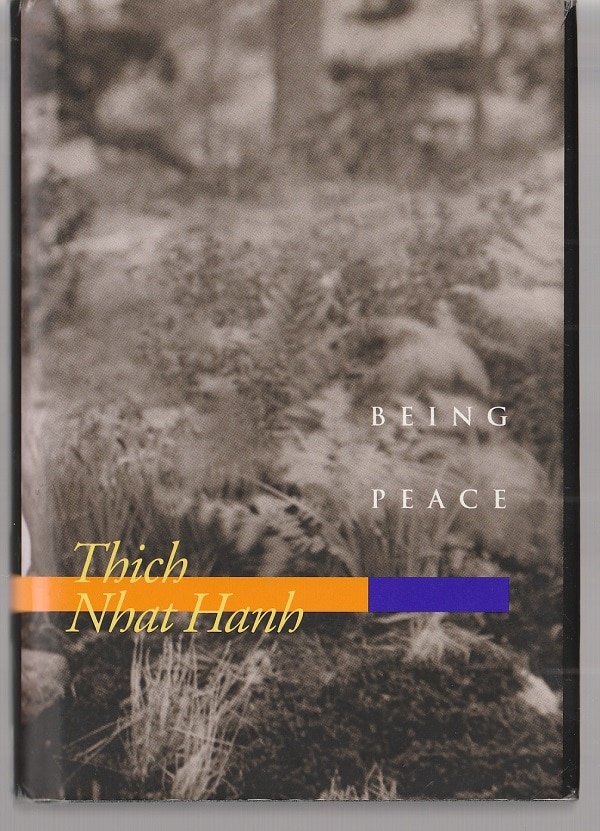

In his 1987 book Being Peace, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk discusses this when listing the Fourteen Precepts of the version of Buddhism that, he believes, may best fit modern Western society, the Order of Interbeing. In fact, it is the initial precept:

First: Do not be idolatrous about or bound to any doctrine, theory, or ideology, even Buddhist ones. Buddhist systems of thought are guiding means; they are not absolute truth.

To anyone familiar with Christianity, Judaism and Islam, this may seem paradoxical — a doctrine that warns against doctrines, a doctrine that insists it is not absolute truth.

To a modern American, swimming in a stormy sea of partisanship, of bitter rancor over hot-button issues — on-off issues, yes-no issues — this may seem disconcerting, even wrong-headed.

Or it might seem refreshingly gentle, open-minded and open-hearted.

“More precious than any ideology”

Being Peace was a book written more than three decades ago by a man who had lived through the war in Vietnam — without taking sides. It is the product of that experience and of an era of international tensions, heightened by the threat of nuclear annihilation.

Yet, it is a book that fits our present world of mutual antagonism, mutual demonization, mutual closed-mindedness. Actually, “fits” isn’t the right word. What I mean to say is that it is a book that addresses the tendentiousness of today’s public debate, not only in the United States but in many other places around the world, and offers a way out.

The ideologies of the right and the left are, as Nhat Hanh formulates it, simply a raft or a finger. They are a way to reach the shore, but they aren’t the shore.

If we cling to the raft, if we cling to the finger, we miss everything. We cannot, in the name of the finger or the raft, kill each other. Human life is more precious than any ideology, any doctrine….

In the name of ideologies and doctrines, people kill and are killed. If you have a gun, you can shoot one, two, three, five people; but if you have an ideology and stick to it, thinking it is the absolute truth, you can kill millions.

“Be ready to learn”

Human knowledge and understanding are finite, limited, incomplete. That’s why any ideology can’t be the absolute truth, even Buddhism.

Similarly, it’s important, writes Nhat Hanh, to be humble about what we think we know, to recognize that it will evolve as we obtain more information. That’s the next of the Fourteen Precepts:

Second: Do not think the knowledge you presently possess is changeless, absolute truth. Avoid being narrow-minded and bound to present views. Learn and practice nonattachment from views in order to receive others’ viewpoints. Truth is found in life and not merely in conceptual knowledge.

Be ready to learn throughout your entire life and to observe reality in yourself and in the world at all times.

One could take those few sentences and use them as a motto for life — as a finger pointing to the moon, as a raft to the shore.

If I hold too tightly to what I “know,” I will never be open to finding out what I don’t know and what I need to incorporate into my understanding of the world.

Stay focused

The other Fourteen Precepts flesh this out further:

Don’t force others to adopt your views. Don’t base your life on the accumulation of wealth or status or pleasure. See suffering; don’t pretend it doesn’t exist.

Let go of anger when it arises. Don’t stir up fighting. Don’t harm other people or take what belongs to them. Don’t kill. Don’t lie. Don’t use other people as if they were objects.

Respect your body. Stay focused on living your life moment to moment, breath to breath.

“Write a love letter?”

As its title suggests, Being Peace is about embodying peace in everyday life.

But, as Nhat Hanh notes, there is an odd paradox about those who are working to bring peace to the world — the peace movement. They’re often filled with anger, frustration and misunderstanding.

The peace movement can write very good protest letters, but they are not yet able to write a love letter….

Can the peace movement talk in loving speech, showing the way for peace? I think that will depend on whether the people in the peace movement can be peace.

As Nhat Hanh explains it, the Buddhist approach is not to see life in terms of allies and enemies, of us and them, but to see everyone as a human being, just like me, just like you.

To fight for peace with anger is self-defeating. Nothing can be accomplished for peace by anyone who is not peace — by anyone thinking in terms of vanquishing enemies.

If we cannot smile, we cannot help other people to smile. If we are not peaceful, then we cannot contribute to the peace movement.

“Don’t blame the tree”

Central to all of this is the effort to understand the other person, even if that other person doesn’t agree with you. To listen, really listen. To be open to hearing what the other person says and what those words means and why that other person says them.

Understanding is the source of love. Understanding is love itself…

When you grow a tree, if it does not grow well, you don’t blame the tree. You look into the reasons it is not doing well.

Although Nhat Hanh doesn’t spell this out, it seems clear to me that this is also true if the tree is blossoming abundantly. You have to look at the reasons for its vibrancy.

In other words, another human being may be a tree that is doing well or not doing so well. By being open to that other person, you can learn what has retarded the tree’s growth or what has nurtured it. In fact, most people are a tree that has a mix of good and bad in its growing.

“Never blame”

Blaming is another word for being close-minded. As Nhat Hanh writes:

Blaming has no effect at all. Never blame, never try to persuade using reason and arguments. They never lead to any positive effect. That is my experience.

No argument, no reasoning, no blame, just understanding.

If you understand, and you show that you understand, you can love, and the situation will change.

In other words, the way to change the situation — to bring peace to a waring world — is to avoid being judgmental.

Instead, work to listen. Work to understand. Work to love.

They’re all the same.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.4.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.