Bessie Smith, Empress of the Blues, liked to spend money on herself and on her friends, such as Ma Rainey, a blues mentor, who got into trouble one evening with the Chicago police because of a wild party with a bunch of young women.

Rainey, like Smith, was a lesbian who also slept with men, writes Jackie Kay, the former poet laureate of Scotland and, like those blues legends, a Black lesbian. On this particular night, the party was so loud that a neighbor called the police, and Kay writes:

“The cops arrived just as Ma and the girls were in the middle of an orgy. There was pandemonium as everyone scrambled madly for their clothes and ran out the back door, wearing each other’s knickers.”

Rainey didn’t move fast enough and ended up in jail. Kay writes that Smith — who “must have been more than sympathetic to Ma’s predicament, having run many such parties herself” — bailed out her friend the next morning.

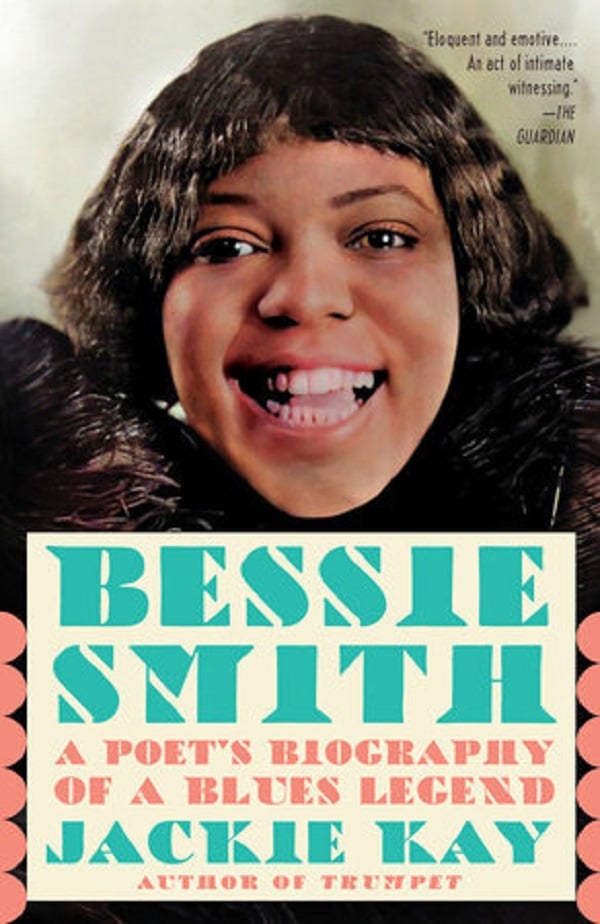

Kay’s Bessie Smith: A Poet’s Biography of a Blues Legend is a full-blooded look at the life and triumphs and tragedies of one of the greatest blues singers of all time, a woman who, at the dawn of the record industry, sold 780,000 copies of “Downhearted Blues” in six months and who, at the age of 43, happy finally with her Chicago bootleg lover, died following a car crash on a dark Mississippi highway in 1937.

As Kay sees Smith, the singer is a big, big-ego woman, hugely talented, earthy and elemental, but also deeply wounded and vulnerable.

“Dark, rough, brutal and real”

Smith’s second husband Jack Gee — who, after a concert, delighted in counting Smith’s money and had few other talents — held her in his sway through a combination of her neediness and his violence. It is as if she were living a blue song. Which, of course, she was.

Kay makes the point many times in her short book that the blues aren’t about make-believe, but about the cold, hard facts of living, particularly living as a woman. They are “dark, rough, brutal and real.”

As a 12-year-old Black girl growing up in Scotland, Kay found in Smith’s blues records a friend, and she writes:

“The reason I loved the blues was because they didn’t appear to be made up in any way. They sprang from life’s source, life’s true well and, well, they tapped into the well of loneliness on the way, allowed for a kind of transformation, a becoming. If you can recognize the other in you, the other side, then perhaps your life can be meaningful in some way you hadn’t imagined.”

Gee hated Smith’s wild drinking sprees and, Kay writes, often battered her for getting drunk. “Jack frequently beat her up very badly, knocking her down stairs and threatening to kill her. The few people on the road who went to her defense were beat up too.”

It was so bad that, at times, Smith “would actually throw herself down the stairs so that she could have genuine injuries in an attempt to avoid being beaten up by Jack.”

“A pure and true ring”

Bessie Smith: A Poet’s Biography of a Blues Legend was originally published (without the subtitle) 24 years ago in the United Kingdom as part of Outlines, a series of books that explored the ways in which “homosexuality has informed the life and creative work of the influential gay and lesbian artists, writers, singers, dancers, composers and actors of our time.”

Now, it is being published for the first time in the U.S. by Vintage Books in an edition that was issued in the U.K. earlier this year.

In a new introduction, Kay writes that “Bessie’s blues are current” and goes on:

“Her narratives are even eerily prescient — she sang about floods, about sexual abuse, about financial crashes, about sudden changes in circumstances, changes in love…In these surreal times, where distinguishing truth is a challenge, Bessie’s voice has a pure and true ring.”

Indeed, Kay asserts, “Bessie Smith is the perfect antidote to these times.”

Yet, what comes shining through Kay’s evocative look at Smith’s life and talent is that her blues are a perfect antidote for any times. Her art is timeless, and it is universal.

“Bessie’s blues moved people. Her voice just got to them. Perhaps she reminded them of the past, of losses, of longing. Her voice seemed to contain history, tragedy, slavery, without pity. It had the ability to stretch beyond even the lyrics of her blues into something more complex.”

“Very happy”

Chicago isn’t much mentioned in Bessie Smith: A Poet’s Biography of a Blues Legend. But, as the story about Ma Rainey shows, Smith’s career took her to the city. It was on the circuit of blues singers. Smith appeared in Chicago, Detroit and other Northern cities, but the vast majority of her live appearances were in the South, often in tent concerts.

And it was a Chicagoan, the minor gangster Richard Morgan, who brightened up the end of the singer’s life.

Morgan — “with whom, for the past six years, she had been very happy” — was driving Smith’s Packard when it hit a National Biscuit Company truck parked without lights along the highway.

Smith’s arm was nearly severed, and, taken to the Afro-American Hospital suffering from shock, blood loss and internal injuries, she died hours later.

There has long been a persistent and apparently erroneous rumor that Smith died because a White hospital wouldn’t accept her. That certainly was an end that many Blacks in the U.S., particularly in the South, could imagine.

Even so, what seems to be the true story — that she got medical help as quickly as was possible — is still rich with the tragic stuff of a blues song.

A happy love affair, a crash on a dark road, a nearly severed arm, death — Smith would have made quite a song of that.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.21.21

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 9.28.21.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.