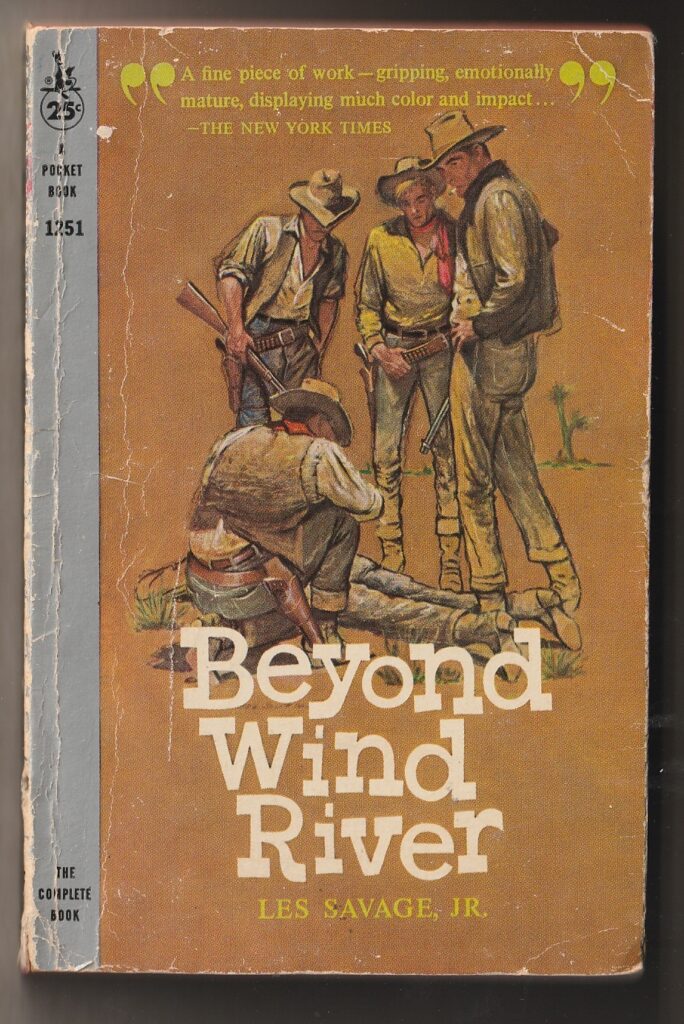

Les Savage Jr.’s 1958 novel Beyond Wind River begins:

Just outside of town Frank Ives caught up with the wagon carrying the dead man.

The dead man is Peter Thayne, the son of Zachary, one of the original settlers in the area around Medicine Lodge, Wyoming. His murder on the open plains outside the town has turned a dispute over a railroad plan into a hate-filled war.

On one side are the Thaynes — the father, his surviving sons Eric and Orin, and his daughter Sabina — and most of the townspeople. Not only would the proposed railroad slice through the Thayne land, but there is also the fear that it would turn Medicine Lodge into a railhead, the sort of lawless place, like Abilene, Texas, where gun-slinging cowboys would let loose with fights and shootings after driving in a herd to send to market.

On the other side is Tom Russell, another early settler, who desperately needs the railroad to come through so he can make the money he needs to save his ranch, the largest in the region. His tough foreman is Cliff Russell, his adopted son better known and widely feared as Fargo. That’s because, two decades earlier, his father Kelly Fargo was a one-man crime scourge until he and his dancehall-girl wife died during a shootout, leaving their six-year-old son.

Stirring up trouble with overheated rhetoric is Jefferson Lee, a newspaper editor with strong opinions who implies in an editorial — with no evidence — that Fargo was Peter’s killer and suggests that Anchor, the Russell ranch, be burned off the landscape.

Sure enough, the next night, the Anchor barn is torched and destroyed and several horses killed. Orin and Eric are seen fleeing, and violence threatens to escalate even further.

The same tragedy

The central character in Beyond Wind River is Frank Ives, the outsider who, through happenstance, ends up getting to know both sides of the dispute as well as Jeff Lee.

Ives is a former newspaperman who’s running from his past. Back in Abilene, he wrote an emotionally charged editorial against Jack Border and the other members of the outfit from the Corkscrew ranch who shot up the town, accidentally killing eight-year-old Lisa Farraday. That sparked a mob that lynched Border. Too late, an eyewitness came forward and said Border had nothing to do with the girl’s death. The killer was a Corkscrew hand who fled and was never captured.

For the past year, Ives has been fleeing his feeling of responsibility for the lynching. And he’s been fleeing Border’s brother Tom who has vowed to kill him in revenge.

Now, in Medicine Lodge, the same sort of tragedy seems to be playing out with Jeff Lee throwing oil on the fire.

Moral questions

Although Savage’s storytelling is clumsy at times, Beyond Wind River is an interesting western, a cut above many others. One reason for that is that it grapples with moral questions that don’t lend themselves to simple black-white answers.

Although Savage’s storytelling is clumsy at times, Beyond Wind River is an interesting western, a cut above many others. One reason for that is that it grapples with moral questions that don’t lend themselves to simple black-white answers.

It looks at — and rejects — some destructive codes of manliness, such as the shootout on Main Street.

It also tempers the idea of a free press with one of a responsible press. (It is interesting to wonder if Savage was thinking of the avid, unquestioning news coverage of the false and baseless accusations of Communism that, during the early 1950s, Sen. Joe McCarthy leveled against scores of innocent people.)

Early on, during a discussion with Lee, Ives asks:

“What have you got here? One man’s already dead. Who’s right? Who’s wrong? Is it criminal to want a railroad in this valley?”

Not the usual “bad guy”

Even more, the novel rises above its genre in Savage’s willingness to present Fargo as a fully rounded character, troubled, prone to anger but also sensitive.

In an early scene, Ives thinks the hothead Fargo is going to start another fight with him, but that’s not what happens when Tom Russell corrects him.

Ives had expected anger, but there wasn’t any. It was gone suddenly from Fargo’s face, replaced by an expression Ives could hardly define. Fargo’s lips were parted, though he didn’t say anything. It made him look young, strangely vulnerable.

In many another novel, Fargo would have been depicted at a “bad guy,” pure and simple. But not in Beyond Wind River.

“Vulnerable” isn’t a word that’s usually used for a “bad guy.” But it’s used twice in the novel in relation to Fargo. The second time is near the end when Fargo is on the run over a death he caused accidentally.

Ives and another man find the foreman drunk in an Indian tent:

His beard stubble was an inch long, matted with burrs and dirt. It gave him a ragged, beggar’s face. His mouth was open and he was snoring softly. There was something vulnerable about his whole position. Ives knew he should hate the man [for the killing]. But in that moment Fargo only looked pathetic.

Beyond Wind River is a novel that deals with complexities — and does a good job of it.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.6.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.