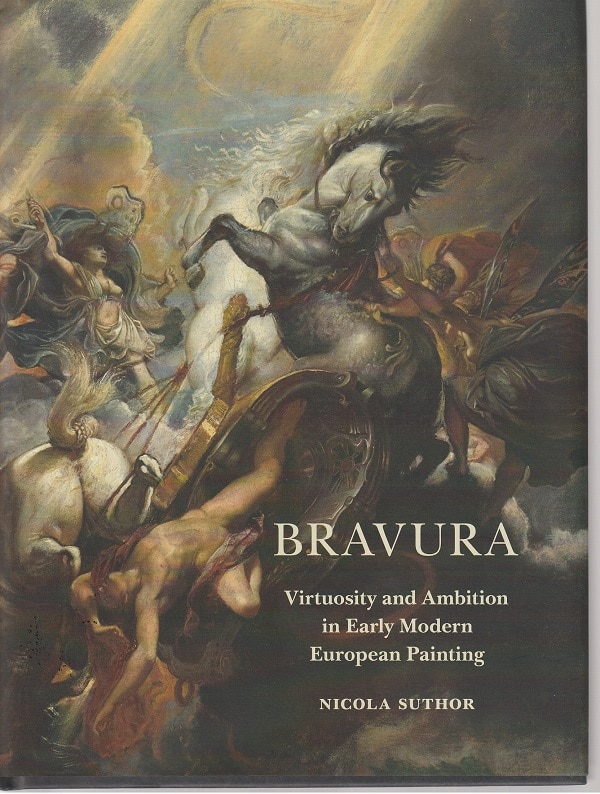

Early in the first in-depth examination of bravura in art, Nicola Suthor, a professor of art history at Yale, tells the story of Raphael and Michelangelo meeting on the street.

Raphael was with a bunch of other men; Michelangelo was alone. As another artist related:

“Michelangelo told him he thought he had met the chief of police, so many men there were with him. To which Raphael replied that he, for his part, thought he had encountered the executioner, who, like Buonarroti, always went about for himself.”

Based on my reading of Suthor’s Bravura: Virtuosity and Ambition in Early Modern European Painting, Raphael could easily be designated as the patron saint of the type of artist who is self-effacing, collegial, rational and even-tempered and who strives to produce work in a modest, self-effacing manner.

Michelangelo, on the other hand, is definitely the patron saint of the other type, the bravura artist, the swashbuckling lone genius (at least, in the artist’s own mind), the flashy, splashy creator of art, aggressive, even violent, and self-referential.

Raphael may have been taunting Michelangelo to say he looked like the executioner. Yet, bravura artists for several hundred years reveled in their bad-boy status. Indeed, the term “bravura” is related to the Italian word “bravo” which means “hitman” or “thug.”

“Theatrically bellicose”

Suthor writes of how many bravura artists adopted

“a theatrically bellicose attitude (whether in real life or on canvas), and, because scenes of battle and martyrdom, patent expressions of domination, garnered most of the attention and praise in contemporary literary discourse, these became the preferred subjects of artists aiming to make bold artistic statements.”

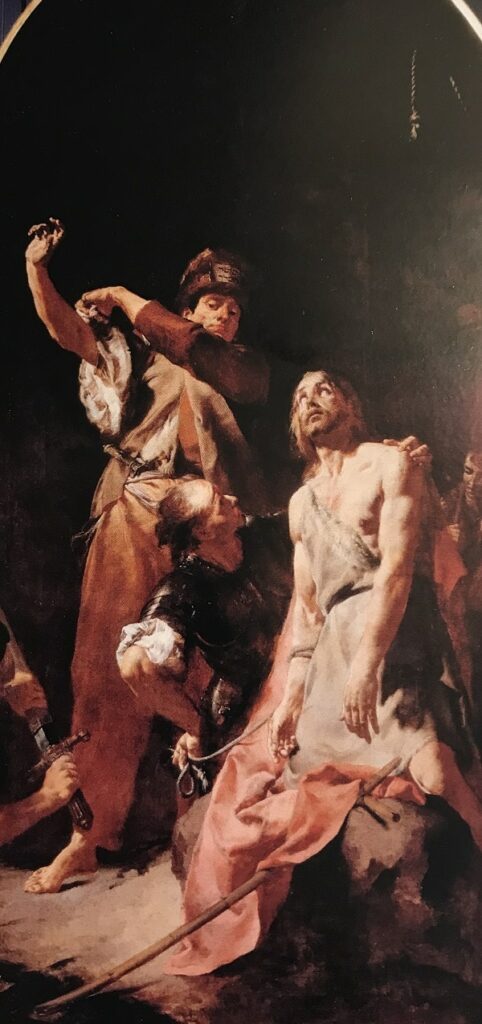

In a chapter titled “Celebrations of Violence,” she notes that depicting executions, for instance, were a particularly violent way to raise an artist’s profile, and a favorite subject was the Herod-ordered killing of John the Baptist, a subject that brought together the brutal and the holy. Such works included Caravaggio’s Beheading of John the Baptist (1608), considered by some art scholars as among his best paintings; Head of John the Baptist by Jusepe de Ribera (1644) and Head of John the Baptist by Domenico Zampieri (1630-1634).

Giambattista Piazzetta’s, though, took this a step further — putting himself into the picture as the saint’s executioner. In his The Beheading of John the Baptist (1744) he is standing above the kneeling saint about to reach for the sword to carry out the death sentence.

“Mesmerizes the beholder”

The association of the creative act of art with the malicious brutality of an execution is “perplexing,” writes Suthor. She suggests that it “addresses the oddity of the human response to the representation of gruesome subjects,” and continues:

The identification of painting with murderous execution (which Piazzetta [pushed] to an extreme) breaks down the affective barriers separating the realms of art and life — and art and death — by provoking an immediate response, namely, the beholder’s compassion. And that compassion becomes the spark that grants life to the subject and guarantees the stunning illusion. The artist’s threatening gesture [either as a painter depicting such a scene or showing himself inside that scene] thus mesmerizes the beholder in order to seize their imagination.

This is a risky artistic approach, it seems to me. The artist is gambling on being able to create a scene that is both grisly and beautiful, lurid enough to compel viewers to look and remember but appealing enough to be palatable.

But risk, it seems from Suthor’s book, is at the heart of bravura.

“Bold sketchiness”

Risk was also present in the bravura artist’s emphasis on tours de force of foreshortening and on the employment of a sketchiness in the work. According to Suthor:

For a bravura artist, a pretended negligence that contrives to conceal becomes an end in itself — attitude becomes form…

Sketchiness, a visual strategy as powerful in its impact as extreme foreshortening of the human body, usurps the viewer’s perception of the artwork, its artifice provocatively captivating their gaze and imagination. Seventeenth century consensus declared Tintoretto, whose name was synonymous with the bold sketchiness of his finished paintings, the bravura painter nonpareil and praised him in language peppered with martial conceits.

When it came to bravura, the subject of the work, in other words, wasn’t simply the work itself. It was also, and perhaps even more, the artist. The goal was to dazzle the viewer with a high-wire act of artistic techniques and skill.

Art not simply as representation, but also as self-promotion.

“In a day”

And, oddly, as a kind of manufacturing. The bravura artist sought to portray himself as so adept and so talented that he could knock off a work in a day or even hours. Suthor writes:

The exceptional ability to finish in a short span of time an artwork that would ordinarily require much longer defines bravura.

She notes that Anthony Van Dyck lived a lavish lifestyle and needed a lot of cash to pay the bills. So, for him, working fast was a necessity.

With expert bravura he was usually able to paint two portraits a day, to which he then only added a few finishing touches. His speed, facilitated by a painterly style grounded in practical expertise, enable Van Dyck to complete even history paintings in a day….

Wealth of perspectives

These observations hardly scratch the surface of Suthor’s deeply researched and comprehensively framed look at an often-misunderstood aspect of art history

Bravura: Virtuosity and Ambition in Early Modern European Painting is an important and long-needed examination of bravura from a wealth of perspectives.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.19.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.