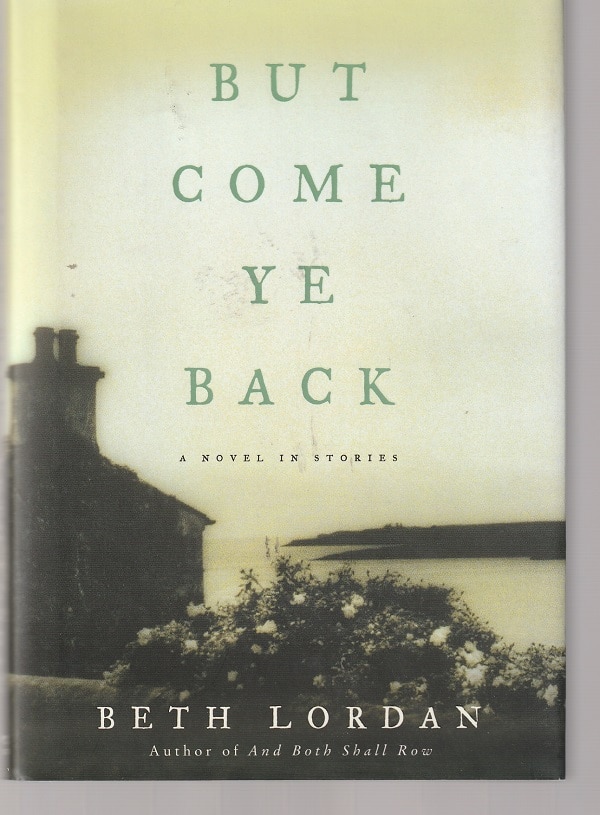

I wonder if anyone has written about the waning years of a happy (and, at times, sharp-edged) marriage with as much sensitivity and nuance as Beth Lordan in But Come Ye Back.

Published in 2004, But Come Ye Back is what’s called a novel in stories. There are seven stories, averaging around 25 pages each, and a novella of a little over 100.

It’s a form that serves Lordan’s narrative well since it provides her a wide latitude in terms of tone, pace and point of view. Even so, at the heart of every section, no matter the literary techniques, beats the relationship — the love — of Mary and Lyle.

As the book opens, Lyle has retired from his accountant’s job in Ohio, and the couple is moving to Ireland, Mary’s homeland and the native soil of Lyle’s parents. He is 65. She is 60. She wants to be back with her sister and other relatives. He goes along, only a bit grumpy.

This is a book about stories not told. About how life is lived, experienced, and how memories are kept, savored, almost unknowingly. Even if you wanted to tell a story, how would you put it into words?

Mary, at one point, considers an aspect of this:

She’d said so little, it seemed now — told him so few things, never mentioned how she took pleasure in seeing his head, the shape of it, or how she thought his hands were beautiful, even if he was a man — beautiful hands.

And other things: she’d seen his eyes full of tears when the boys were baptized and never said a thing about it, and she’d seen how he would put the newspaper to the side for a long time after he read something sad, about children or poor people, for all that he went on about the politics. She’d never told him that his smell was a joy, a rich wheaten smell that was almost a taste, and that when he was away, she’d take his pillow for her own just to have that smell of him close…

“Tribal, intimate revenge”

Lyle and Mary met at a picnic in Boston where he was living with his stroke-crippled mother and she was a governess. Over the course of two months, they went on two dates. Kissed once. Then, for Thanksgiving, Lyle called to ask her to dinner to meet his mother.

But Mary had gone back to Ireland to care for her father in a dagger thrust-and-twist of “tribal, intimate revenge” for escaping to America. “Did you think you were away? [the father] says.”

It was a prison, but what eventually does Lyle do? He flies across the Atlantic to Galway, buys a rickety bicycle and, with constant wobbling, rides out to her family farmhouse in all ridiculousness — and saves the day.

This is a story the couple’s two sons, Kevin and Jimmy, have never heard.

If you are in any sort of close relationship — marriage, friendship, parent-child, sibling — how much do you put into words what you know and feel about the other person? How much can you?

Finding the words, mining the feelings

That is the beauty of Lordan’s story and her prose. She finds the words and mines the feelings of Mary and Lyle’s love, and she brings them to light — even if Mary and Lyle can’t, won’t or have no occasion to.

Lyle, a sturdy, plan-full gardener, lays out on paper the groupings of flowers that he will plant to decorate Mary’s Curtin family gravesite for the annual Cemetery Day.

“It’s lovely so,” she said, though it was little enough to say, about the gift he’d planned here, for her people, and little enough to say about her gratitude that the two of them were here in this room in this light in this moment, exactly as she had hoped and imagined they might be….and she put her own hand on his shoulder. “It’s lovely.”

The praise and the caress, as she knew they would, made him gruff, and he said, “It’s pretty simple…”

Mary knew the praise and caress would make Lyle gruff. She doesn’t ever tell him this. How would she bring it up? How would she phrase it? Would it result in a different gruffness?

I’m sure my wife knows what would make me gruff in one way and gruff in another. Probably, like Mary, she takes pleasure in that knowledge, and takes pleasure in giving me praise and a caress — or whatever their equivalent is.

And how much of what I know and feel about my wife is never put into words? Even to myself?

Coughing

Mary has been sick for days. In the early morning hours, she is sitting up in another room, but Lyle can hear her body-draining wracking coughs.

Across the hall, alone in their bed, Lyle hears the cough and braces himself against it, as if it were his own. He wishes, without forming the wish with words, that it were his cough, that he, not his wife, were sick.

He wishes this not because he loves her, although he does. He wishes this because the sound of her coughing nearly overwhelms him with a dread that he refuses to recognize as familiar still, although his boyhood as the only child of a widowed mother who coughed is now long past, and his mother’s stroke and extended illness and death are now long past, and Mary has never in his life with her been so ill.

He is neither heroic nor selfless; if he were coughing, as Mary has been for a week, he would be peevish and demanding, but he is not coughing. He is lying alone in his bed, rigid with dread….

Stories and knowledge

There is tragedy in But Come Ye Back, tensions and reconciliations, daydreams of other lovers, irritations, “mean pleasures,” sharp exchanges and gentle whisperings.

There are the stories, and there is the knowledge. Who knows us as well as those who love us? Who know me as well as my wife does?

On the day the couple moves into their new Galway home, they have a small spat in the kitchen. Lyle can’t find the box of records. Mary offers to locate it among the chaos of cartons.

“No, I don’t need it tonight,” he said, spiteful, and tossed the paring knife into the sink.

“That’s good, so — I’m about to go to bed.” She turned from him, an old habit of giving him privacy to recover from his anger, but she could see in her mind every gesture he’d make — he’d smooth his hair with both hands and then pat his palms twice against his thighs as if checking his pockets, and then he’d lift his chin and, with his right hand, smooth his throat in two quick passes.

That is the story of love.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.24.13

This is the second time I’ve read But Come Ye Back and the second time I’ve reviewed it. You can find my 2013 review here.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.