Ask the average American, and you’d most likely find that the British royals have a pretty dopey reputation.

For nearly half a century, there have been all these tabloid stories about the scandalous behavior of a largish clan of people who don’t seem to do much of value. They show up; that’s their job. The brotherly spats and occasional or maybe routine adulteries give them a tackiness that all their fancy clothes can’t hide. Queen Elizabeth II — the one exception — was an admirable stand-up woman who seemed endlessly beset by her soap opera of a family.

Of course, this is the crown once worn by Henry VIII who, famously, went through six wives, cutting off the heads of two. And once worn by George III who, famously, is known for his sporadic madness and for losing the colonies in the American Revolution.

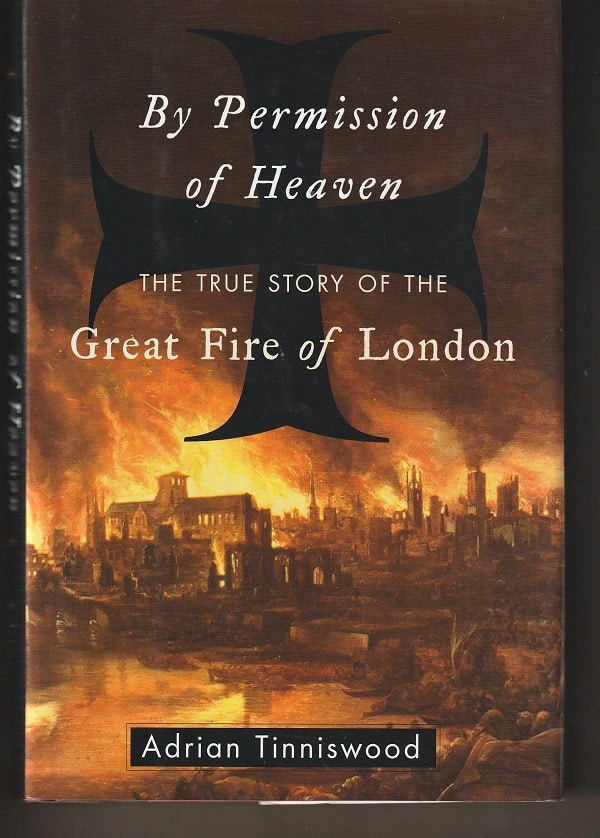

So, for an American, it is a bit startling to read, in Adrian Tinniswood’s By Permission of Heaven: The True Story of the Great Fire of London, how the king and his brother were not just competent and energetic in personally fighting the fire that in September, 1666, consumed most of London, but were even heroic.

To be clear, the king here is Charles II, known to later generations as a randy guy with at least 12 illegitimate children by various mistresses. (Wikipedia has a separate page with links to entries on ten of his known or presumed girlfriends.) His brother who later became James II made a botch of his short time on the throne and had to flee although not without taking the time to throw the Great Seal of the Realm into the River Thames.

“Exposing their persons to the very flames themselves”

During the four-day battle against the fire, however, Charles and James were stellar.

Indeed, as Tinniswood notes in his 2004 book, private letters of the time marveled “over the fact that the two men stood up to their ankles in water and manned pumps for hours on end.” He continues:

Both brothers were admired for their efforts; both were applauded for the fact that “with incredible magnanimity [they] ride up and down giving orders for the blowing up of Houses with Gunpowder to make voyd spaces for the fire to dye in, and standing still to see those orders executed, exposing their persons not only to the multitude but to the very flames themselves, and the Ruines of buildings ready to fall upon them and sometimes laboring with their own hands to give example to others.”

On the western edge of the city, as the fire was nearing the Palace at Whitehall, where the King and the government were headquartered, James, then Duke of York, was directing the efforts to use hooks, picks and whatever else would work to tear down structures to starve the fire of fuel. As one eyewitness wrote later, with the creative spelling of that era:

“The Duke of York hath won the hearts of the people with his continuall and indefatigable paynes day & night in helpeing to quench the Fire.”

“With sweat and dirt besmear’d”

While Charles won accolades, it was his brother who “received the greatest praise for his ability to keep his head in a crisis, his determination to stop the fire.” One of many contemporary poets to turn the Fire into verse, Simon Ford, wrote:

Next, Princely York, with sweat and dirt besmear’d

(More glorious thus, than in his Robes) appear’d.

Another eyewitness, John Rushworth, described James “handing buckets of water with a much diligence as the poorest man that did assist,” adding that “if the Lord Maior had donn as much, his Example might have gone Far towards saveing the Citty.”

“Piss it out”

That Lord Mayor, Thomas Bludworth, had gotten his job because of his Royalist sympathies rather than any leadership ability. He was not up to the task when he was called to the scene of the small house fire in Pudding Lane that started it all. Tinniswood writes:

True, he was prompt to arrive on the scene; but what he saw there — the raging fire, the chaos and confusion and heat and noise that always accompany such accidents — terrified him.

The more coolheaded men among those fighting the fire insisted that nearby homes, untouched so far by the fire, needed to be torn down to contain the blaze, but the Lord Mayor would have none of that.

But Bludworth simply said that he dared not do it without the consent of the owners. Most of the shops and homes were rented, so those owners were God knew where. Not in Pudding Lane, for sure.

Pressed, Bludworth just blustered:

The fire wasn’t all that serious, he said. “A woman can piss it out.” And with that he went home to bed and a place in the history books.”

“Hell broke loose”

The title of Tinniswood’s book By Permission of Heaven is taken from the inscription on a large plaque installed in 1681 at the site of Thomas Farriner’s bakery in Pudding Lane where the Great Fire of London started. Tinniswood uses the opening words of that inscription as an epigraph to his book:

Here, by ye Permission of Heaven, Hell broke loose upon this Protestant City.

There is, however, a bit of misdirection going on here. Or, at least, Tinniswood is employing these words to make one point while also knowing that he will come back to them at the very end of his book to make a very different point.

On the face of it — at least, to me — the title indicates that the Great Fire (‘Hell broke loose’) was an act of God (“By Permission of Heaven”). And that’s what the official inquiries into the fire determined.

Not that the public didn’t have other ideas, even as the blaze was still roaring. Many suspected Papists of setting the fire either an act of religious violence or as an effort to help England’s war-waging Catholic enemies, France and the Netherlands.

“Guilty of it”

Indeed, in the immediate aftermath of the fire, Robert Hubert, a 26-year-old watchmaker’s son from Normandy, told investigators that he was a member of a gang of 24 arsonists who started the fire: “Yes, sir, I am guilty of it.” Tinniswood writes:

In spite of London’s real need to believe that the Fire was an act of malice rather than an act of God, there was considerable disquiet over Hubert’s story.

For one thing, he contradicted himself in retelling his story. For another, he claimed to be Catholic although most friends and acquaintances said he was a Huguenot, a Calvinist Protestant.

“Nobody present credited any thing he said,” the Earl of Clarendon later recalled. Lord Chief Justice Kelyng, a formidable figure with a reputation for sternness, heard the case at the Old Bailey and told Charles II that Hubert’s story made little sense, “all his discourse was so disjoined that he did not believe him guilty.”

And it seemed that Hubert would avoid punishment. He was, it appears, the sort of defendant who, today, would be identified as not in his right mind. But Hubert, apparently enjoying his celebrity, wouldn’t retract his confessions, and, 58 days after the start of the fire, he was hanged.

“The hand of God, a great wind, and a very dry season”

Nonetheless, a Parliamentary inquiry into the fire went forward, and, as Joseph Williamson, Under-Secretary of State and the chief propagandist for Charles II, noted:

“After many careful examinations by Council and His Majesty’s ministers, nothing has been found to argue the fire in London to have been caused by other than the hand of God, a great wind, and a very dry season.”

Sir Thomas Osborne, who served on the Committee, agreed that “all the allegations are very frivolous, and people are generally satisfied that the fire was accidentall.”

“The malicious hearts of barbarous Papists”

And so it stood until 15 years later when another wave of anti-Catholic hatred was sweeping the British populace and the large plaque was plunked onto Pudding Lane. Here’s the full text of the inscription:

Here by ye Permission of Heaven, Hell broke loose upon this Protestant city from the malicious hearts of barbarous Papists, by ye hand of their agent Hubert, who confessed, and on ye Ruines of this Place declared the fact, for which he was hanged, (vizt.) that here began that dredfull Fire, which is described and perpetuated on and by the neighbouring Pillar. Erected Anno 1681 in the Majoraltie of Sr. Patience Ward, Kt.

As Tinniswood comments:

The Fire was not an act of God, after all, it seemed, but an act of terrorism. Its commemoration was not a call to reconciliation, but a cry for revenge.

As happens often with events and people of the past, the controversialists of 1681 were using the Fire as a political weapon, the facts and truth be damned.

A rich read

This pariah status of Catholics, however, gradually weakened over the next century and a half, concluding with the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829.

The following year, the Court of Common Council ordered the plaque with its now-offensive words to be removed. “The Pudding Lane tablet ended up in two pieces in a cellar,” Tinniswood writes, “where it was found in 1876 and presented to the Guildhall Museum.”

Adrian Tinniswood’s By Permission of Heaven: The True Story of the Great Fire of London is packed to the brim with anecdotes, descriptions and insights into the times and human nature.

It is a rich read about the near-death and beginning rebirth of one of the great cities of the world.

And it benefits greatly not only from Tinniswood’s ability to find and weave together the many strands of the people and places of the Great Fire but also from his great good luck to be able to mine the sprightly and telling prose of an eyewitness who happened to be the great diarist and great commentator of Restoration England, Samuel Pepys.

Patrick T. Reardon

9.5.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.