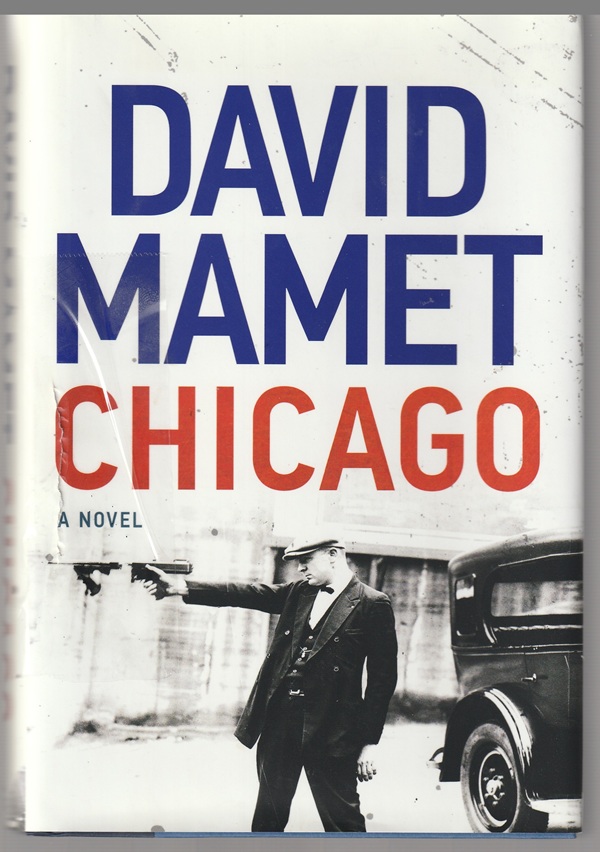

On the title page of David Mamet’s 2018 book, it says: Chicago: A Novel. It would have been more accurate to say: Chicago: A Myth.

The book, well-written and well-paced, certainly reads like a novel. Yet, the story is set in a mythic city in a mythic time (about a century ago) with a lone hero going on a search — like Gilgamesh, like Odysseus — that takes him into marvelous, exotic and dangerous places.

That lone hero is Mike Hodge, a thirty-year-old Chicago Tribune crime reporter whose Irish Catholic girlfriend is murdered before his eyes, sending him into a profound, booze-soaked depression. So deep is his despair and self-hate that he’s able to extricate himself only with the help of friends and through his decision to find and wreak vengeance on the girl’s killer.

In his travels across the landscape of Chicago and its hinterland, Hodge enters the lair of South Side mobster Al Capone, not once but twice. He meets an ex-safe and vault guy in a Chinese restaurant, and a friend in the amazingly clean and competent and uncorrupted Kedzie Baths, and intelligence expert Sir William Frederick at the British consulate where they talk of the Irish Republican Army and tommy guns.

Hodge frequents (although not as a customer) a brothel called Ace of Spades on South Michigan Avenue, operated by the 48-year-old Peekaboo, an earthy oracle-like figure. Indeed, she and all other all Blacks in the book have a preternatural access to knowledge and insight through their sheer Blackness — whites don’t notice them. As Marcus, a trusted Peekaboo employee, explains:

“White folks, let me begin with this: see nothing….You don’t realize is that black folks see everything. And, as importantly, hear everything.”

“Received chronology”

Right after the book’s title page, Mamet inserts the sort of alert to readers that is almost always a pro forma thing but not in this case:

This book is a work of fiction. It is compounded of historical fact, myth, and imagination. Received chronology, having been, at some points, an impediment to narrative, has been jostled into a better understanding of its dramatic responsibilities.

That’s an arch way of telling the reader not to trust, in historical terms, the facts in Chicago.

Mamet, of course, is best known as a playwright, screenwriter and director. He has written more than three dozen plays, two of which have won the Pulitzer Prize. He has written 25 screenplays, directing many of them, and was twice nominated for an Academy Award. He has written more than two dozen books, four of which are novels, the last of which is Chicago.

Which is to say, he can reconfigure chronology if he wants to and who’s going to tell him no?

The non-death of Dion O’Banion

The book hinges on the year when Hodge’s girlfriend is murdered, and that seems to be 1928, based on a recollection Hodge has right after the killing. He had been an American flier in Europe during the Great War, most of the time carrying an inch-long celluloid rabbit. Back in Chicago, still in uniform — so, say, about 1919 — a whore asked him about it, and that was nine years ago.

The book hinges on the year when Hodge’s girlfriend is murdered, and that seems to be 1928, based on a recollection Hodge has right after the killing. He had been an American flier in Europe during the Great War, most of the time carrying an inch-long celluloid rabbit. Back in Chicago, still in uniform — so, say, about 1919 — a whore asked him about it, and that was nine years ago.

OK.

A major theme of the novel is the turf war between the Capone gang on the South Side and the North Side gang headed by Dion O’Banion — who, as it happens, died in 1924…well, was murdered in his flower shop. (Flower shops, by the way, play an important-ish role in Chicago. Hodge’s girlfriend worked at the flower shop that supplied North Side mob funerals.)

After Hodge gets his revenge — say, in 1930 or so — he writes a book about the war and then comes back to the Tribune newsroom where all the talk is about the trial of Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, the two rich Hyde Park teens who kidnapped and killed Bobby Franks.

It’s an example of how one day’s big story will get overshadowed by the next day’s — even if, in the real universe, the murder and the conviction of the young men actually happened back in 1924. Similarly, a short time before his girlfriend is murdered in 1928, Hodge and a cop are talking about the St. Valentine’s Day massacre — which, in our universe, won’t talk place until the next year.

Its mythic quality

Don’t get the idea that Mamet is being sloppy. He knows exactly what he’s doing. He’s jamming together in his novel all of the great crimes and crime figures of 1920s Chicago to add to the book’s mythic quality.

The novel’s action isn’t taking place on the street grid of the actual Chicago but of a city of legend — a legend that Mamet is creating.

Chicago is a saga of North Side versus South Side (hence, the need for O’Banion as a heavyweight counterbalance to Capone), a tale of multiple layers of civic corruption and the cleverness of criminals, a story of a stable social landscape — the balance of mob powers in the city — violated by outsider justice, and a hagiography of newspaper reporters.

I’m not sure of the purpose in some of the more minor wrinkles in Mamet’s Chicago, such as his designation of Halsted Street as the city’s longest street (it’s Western Avenue).

Also, a key scene very late in the book takes place under the Division Street bridge along the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, even though the canal only goes through the South Side and Division is a North Side street and its bridge is over the North Branch of the Chicago River.

I suspect Mamet thought the Sanitary and Ship Canal sounded like a mob kind of place for a moment of violence.

Belgium nuns

Let me go back to the hagiography of reporters, i.e., the depiction of them as saints. But, first, I need to mention the Belgium nuns.

At least four times in Chicago, Hodge or another of Mamet’s characters mention an atrocity story from the Great War — the rape of Belgium nuns. Early in the novel, for instance, Clement Parlow, Hodge’s best friend and reporter desk mate, facetiously suggests that the Protestant German soldiers raped the Belgium nuns in the war because of their lack of a Catholic adoration for their mothers,

He, though a noncombatant, assumed the atrocity stories were myth, as he assumed most stories which inflamed or ratified passions were myths, as indeed were most stories presenting themselves as news.

Although the story of the rape of Belgium nuns comes up often, no one takes it seriously. Indeed, even earlier in the book, a drunken Hodge uses the story to make a joke. Standing in a bar, he tells a group of reporters:

“I have a confession to make. I, like plucky little Belgium, and her noted nuns, have been getting fucked…I have been debauched by journalism, but. But….”

“Believe little and nothing”

Mamet uses the repeated story of the Belgium nuns to make a point about the mythic nature of newspaper news in the 1920s and, by extension, in all times and, by extension, in all areas of human life. Stories are larger than facts. Stories are told to fit into expectations. The stories of the St. Valentine’s Day massacre and Leopold and Loeb and the mob wars all rise above or beyond their facts (hence, Mamet’s desire to squeeze them all into his novel).

A sign in the Tribune newsroom reads: “Believe little that you see and nothing that you hear.” It was the dogma of the faith of Hodge and all reporters as they pursue their craft — “an exercise in folly, wickedness, and deceit” based on the recognition that true knowledge of the world required “doubt not only of his fellows, but of his own mental processes and reason.”

Yet, in the world of doubt, there was a reward — “that, occasionally, he might discover the truth.”

The constant practice of doubt as to the material, and disbelief of all human testimony, created, in reporters, as in the judges, the cops, the nurses, and others of the tribe of the night, various instincts. Having seen lies almost exclusively, the rare instance of the truth was, to them, easily identifiable…Put on the scent of truth, they proceeded fairly oblivious to blandishment, intimidation, or distraction.

The search for meaning

My suspicion is that Mamet, in this sainting of reporters, is using them as a metaphor for any writer or artist who is willing to approach life with doubt and a desire to look at even the worst of things in order to find the kernel of truth.

So, it seems to me, Chicago is a story — a myth — about Hodge’s search for truth. And, in its way, about Everyman’s search for truth.

The novel is a kind of murder mystery, and, like all of that ilk, there is a ring of morality to the events taking place — a ring of wrongness and rightness. There is a puzzle at the heart of Chicago, the enigma of what it means to be alive and breathing.

That’s what Hodge is searching for — the meaning of the girl’s murder and the meaning of his role in humanity. Like any mythic hero, he suffers much in his search. And, in his search, he finds himself.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.27.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Nice, fair review of what seems to be a jumble of a book. I read his semi-memoir last year and thought it was pretty sloppy. Glengary is back on Broadway anyway, albeit with poor reviews on its presentation. Pat, what is the last great Chicago book you’ve read?

As far as non-fiction: “The Coast of Chicago” by Stuart Dybek.

I mean, fiction — “The Coast of Chicago”

I think “Chicago” is a purposeful jumble on Mamet’s part. It’s a good read. As for the last great Chicago book, in terms of non-fiction, it’s “Muddy Ground.” https://patricktreardon.com/book-review-muddy-ground-native-peoples-chicagos-portage-and-the-transformation-of-a-continent-by-john-william-nelson/