If you want to know Chicago, you gotta know the grid.

If I tell you I live at 6220 North Paulina Street, you know that my two-flat is 62 blocks north of Madison Street, or just under eight miles, the rule of thumb being eight blocks to a mile.

Where’s Paulina? 1700 West. When you hear that, you know it’s 17 blocks, or just over two miles west of State Street.

It’s even easier on the South Side. If I’m going to 324 West 35th Street (where Comiskey Park used to stand), I’m heading 35 blocks south of Madison and three blocks west of State Street.

Chicago’s flat, and that means that the grid can ramble on without running into a ravine or a hill or much of anything that would cause it to dead end. (It’s true a lot of streets come to a halt at the Chicago River, but, in most cases, they pick up again on the other side.)

As a result, many of the city’s streets flow in a straight line seemingly forever. You can, for instance, start at Michigan Avenue and ride Madison Street west for 21 miles to the far edge of Lombard. Or set out from the Chicago History Museum and head west on North Avenue for 24 miles to Carol Stream where, for suburban sorts of reasons, the street turns a bit to the northwest and goes on for another four miles.

Thank or blame James Thompson. He’s the surveyor from southern Illinois who, in 1830, laid out the first grid of streets and alleys.

In doing so, he created 58 rectangular blocks over 240 acres of pretty much open land, bordered by, as he named them, State Street on the east, Madison Street on the south, DesPlaines Street on the west and Kinzie Street on the north. Thompson did this work on behalf of Illinois and Michigan Canal Commissioners who needed the land subdivided so they could sell lots to fund the construction of the canal.

He was turning the prairie into real estate.

“Relentless gridiron pattern”

John William Reps understands why Thompson did what he did. But he’s no fan.

On the one hand, Reps — who was named the father of modern American city planning history in 1996 by the American Planning Association — recognizes how useful the street grid has been, not only in Chicago but throughout the United States. Still, he is one of many urban historians and theorists who consider the street grid a simple formula for monotony.

In his 1979 monumental work Cities of the American West: A History of Frontier Urban Planning, Reps shows a map of Thompson’s plat of Chicago — one of over five hundred nineteenth century planning maps in his book — and comments:

“It was this unimaginative design that established the beginning of Chicago’s almost unending and relentless gridiron pattern as the Canal Commissioners continued to sell off land in their alternate sections and as purchasers of other sections from government land office filled in the intervening spaces with continuations of Thompson’s north-south and east-west streets.”

That thing about continuing the Thompson grid is important. As Reps’s book shows, many towns and cities have more than one grid, and that causes confusion — but not as much as in those places, such as Denver, Austin and San Francisco, cursed with several grids, each oriented in a different direction.

And the confusion is even greater in the many East Coast cities and towns without any grid at all. If you’ve ever tried to get around New York city away from Manhattan, you’ll know what a challenge it is to find any address without some GPS help. Despite this, Manhattanites are inordinately proud of the grid the city retrofitted onto the island in the 19th century. Take a look, for instance, at The Greatest Grid website and at this 2012 book, titled, no surprise, The Greatest Grid.

The “geometric grasp” of the grid

Thompson’s plat of the city’s streetscape resulted in boom-and-bust waves of real estate speculation.

And it wasn’t uncommon, as an observer wrote in 1840, for lots “in streets not yet marked out, except on paper, [to be] sold from hand to hand at least ten times in the course of a single day.” With each sale, the price would rise so that, by the end of the day, “the evening purchaser, at the very least, [paid] ten times as much as the price paid by the morning buyer for the same spot!”

And it wasn’t uncommon, as an observer wrote in 1840, for lots “in streets not yet marked out, except on paper, [to be] sold from hand to hand at least ten times in the course of a single day.” With each sale, the price would rise so that, by the end of the day, “the evening purchaser, at the very least, [paid] ten times as much as the price paid by the morning buyer for the same spot!”

In the long run, of course, Chicago and its grid turned out to be a good bet, and Reps writes:

“By the end of the century Chicago, like Saint Louis, was a densely built-up community with towering office buildings, smoky industrial plants, a bustling waterfront, and with a vast grid of streets clutching in their geometric grasp tens of thousands of houses stretching outward on the flat prairie.”

Boundless open spaces

At the end of the fifteenth century when Christopher Columbus stumbled on what became known as the New World, there were permanent Native American settlements, even Aztec and Inca cities, scattered across the enormous expanse of the Americas. For the most part, though, the continents were made up of boundless open spaces.

These were spaces that settlers from Europe, who began flooding the thirteen British colonies and later the fledgling United States, sought to fill, starting with the creation of towns. It was an unprecedented undertaking. Never in world history had such an immense area been planned and plotted from scratch for human habitation, and the vast majority of the planning and plotting took place between 1800 and 1900.

Anyone familiar with U.S. history is well aware of the unrelenting push of individual pioneers and groups of homesteaders ever westward across the continent in search of new and greater opportunities. Less recognized is a similar westward movement of town planners, usually moving in advance of the incoming settlers.

Those planners were religious leaders, government agents, mining companies, railroads but most often land speculators looking to make a quick buck. And, in laying out the streets of their New Berlin or New London or New Paris, they were all thinking about the grid — in some cases, seeking an alternative layout, but, much, much more often, embracing that system of straight-line streets meeting at right angles.

“Prevailing use of the gridiron”

Cities of the American West, like Reps’s two earlier books The Making of Urban America (1965) and Town Planning in Frontier America (1969), notes that town planning in the East and the West was characterized by “the prevailing use of the gridiron street system with its rectangular blocks and lots.”

Indeed, so extensive was the use of the grid that it’s easy to get the idea that it was an American brainchild.

Not so, Reps writes, the grid “has been the plan-form used in all great periods of mass town founding in the past: Mediterranean colonization by the Greeks and Romans; medieval urban settlement in southwestern France, Poland, and eastern Germany; Spanish subjugation of Latin America; and English occupation of Northern Ireland.”

The grid certainly does make sense for anyone wanting to take a field and speedily turn it into property. Reps notes:

“Easy to design, quick to survey, simple to comprehend, having the appearance of rationality, offering all settlers apparently equal locations for homes and business within its standardized structure, the gridiron or checkerboard plan’s appeal is easy to understand.”

“Imagination stupefied”

Nonetheless, as Reps makes clear in his three books, the grid is far from perfect. Indeed, he argues that the grid can “be monotonous, inappropriate for hilly terrain, lacking in focal points for important buildings, monuments, or open spaces, and hazardous because of too-frequent intersections.”

A case in point, particularly in terms of monotony and topography, is San Francisco.

Already, in 1855, a history of the city was complaining about a street layout that casually ignored the hilliness of the place:

“The eye is wearied, and the imagination quite stupefied, in looking over the numberless square — all square — building blocks, and mathematically straight lines of streets, miles long and every one crossing a host of others at right angles, stretching over sandy hill, chasm and plain, without the least regard to the natural inequalities of the ground.”

“Up a grade, which a goat could not travel”

Fourteen years later, in a magazine article, M.G. Upton complained that, to the designers of San Francisco’s grid:

“it made but very little difference that some of the streets…followed the lines of a dromedary’s back, or that others described semi-circles — some up, some down — up Telegraphic Hill from the eastern front of the city — up a grade, which a goat could not travel — then down on the other side — then up Russian Hills, and then down sloping toward the Presidio.”

Complicating matters was that the city already had two main street grids that met at an awkward 45-degree angle, and several more would be added over the next century and a half.

San Francisco, though, wasn’t alone. Throughout Cities of the American West, Reps offers maps of grids that planners imposed or tried to impose on inappropriate sites, such as Cripple Creek, Colorado where, in an 1896 map, the grid undulates over a hilly landscape.

“The costs of such ventures”

Chicago, San Francisco and even Cripple Creek are newly laid-out towns that are still with us today. Many others, however, withered and died, or died aborning.

The thing was that, for a go-getter, it was pretty easy to get a new town started, and there was money to be made by selling off at least some of the lots before heading off with the profits to new enterprises. As Reps writes:

“Speculators were quick to seize the opportunity to dabble in the founding of cities. The costs of such ventures were modest, and to advertise one needed only to pay for notices in the newspapers and for printed plats to be hung in hotel lobbies, real estate offices, and boat landings.”

“On paper”

In his 1867 book Beyond the Mississippi, Albert Richardson, a journalist and biographer of U.S. Grant, opined that

“on paper, all these towns were magnificent. Their superbly lithographed maps adorned the walls of every place of resort. The stranger studying one of them [for New Babylon, Kansas] fancied the New Babylon surpassed only by its namesake of old. Its great parks, opera-houses, churches, universities, railway depots and steamboat landings made New York and St. Louis insignificant in comparison.”

And, at this point in his book, he inserted a copy of that map, titled “The City of New Babylon on Paper.” Then, he went on to say that, if a potential investor actually went to the site, he’d be likely to discover, in most cases, “one or two rough cabins, with perhaps a tent and an Indian canoe on the river in front of the ‘levee.’ ” And he offered an illustration titled “The City of New Babylon in Fact.”

And it wasn’t just the speculators who were willing to cut a few ethical corners to make a sale. Reps tells the story of the three-member commission who, in 1867, were assigned by the Nebraska legislature to establish the state capital in Lincoln but were having trouble selling the new city’s real estate.

“The commissioners resorted to an old trick of private town speculators: rigging the bidding to make it appear that Lincoln town lots were in substantial demand.”

They got allies to make bids on the lots, driving up the price, and, after five days of sales, netted $35,000, the equivalent of more than $600,000 today. Eventually, the sale of land in Lincoln brought in $300,000 for the state, or $5.2 million in present-day dollars.

Caveat emptor

Certainly, when it came to lots in newly platted towns, it was always a case of buyer beware.

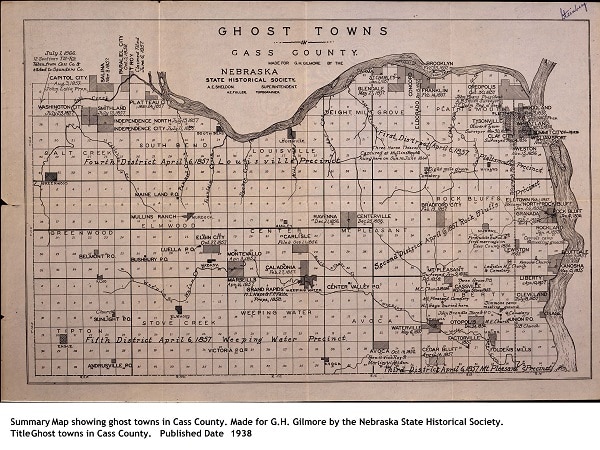

In fact, in the single county of Cass in Nebraska, so many sure-fire towns failed to thrive that, in 1938, the Nebraska State Historical Society drew up a map showing the locations of 64 ghost towns there.

By contrast, the leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints weren’t speculators. Starting with their martyred founder Joseph Smith and especially under the direction of Brigham Young, the Mormons created towns as a means to create religious communities.

This was also a strategy employed to embed their people and faith in Utah and the nearby region throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Indeed, by 1900, that area was filled with at least 500 villages and cities founded by the religious leaders.

“A crude but workable community”

One type of town that was rarely planned in its initial stages of settlement was the mining camp which grew into existence overnight as prospectors flooded into the area of a recent strike of gold or another precious metal.

It was an anarchic and seemingly every-man-for-himself world. Yet, Reps points out that the need for organization amid the chaos was imposed with surprising rapidity:

“What is remarkable is that these mining camps, which sprang up overnight in a region without civil government, populated by persons who were utter strangers, and whose inhabitants were motivated solely by the desire to enrich themselves soon evolved their own effective system of local government.

“A crude but workable form of community law and administration provided the basis for adjudicating conflicting mining claims, raising funds for supplying public services, dealing with criminals, and providing other functions necessary for community existence.

“The popular view of mining camps as lawless, brawling, rough and disorderly, while not entirely incorrect, ignores important achievement in self-government.”

At the same time, a city might seem to be well on its way to urban tranquility when an event would occur as a reminder of its earlier rawness, such as in Seattle.

Reps points out that a city historian, writing in 1890, crowed about the way, during the previous decade, the local moneymen had “built warehouses, graded streets, planned the erection of a big hotel, and a pretentious opera house,” showing how “Seattle was in the midst of its transition from a frontier town to a great commercial city.”

Nonetheless, Reps adds drily:

“The transition was not quite complete, for, as [the historian] recalled, ‘in the very midst of this business activity, three murderers were lynched in the public square.’ ”

“At your service!”

The cities of the West with their street grids and warehouses and opera houses were very much like the cities of the East. One reason for that: Many of the items that were used in creating a new town came from back East — even houses.

Writing in 1868, Louis Simonin, a French mining engineer, visited the newly platted Cheyanne, Wyoming, and commented on the stores with ready-made clothing, as well as the town’s book shops, the printing shops, the restaurants, hotels and two newspapers. And not only that:

“Houses arrive by the hundreds from Chicago, already made, I was about to say, all furnished, in the style, dimensions, and arrangements you might wish. Houses are made to order in Chicago, as in Paris clothes are made to order at the Belle Jardinière. Enter. Do you want a palace, a cottage, a city or country home; do you want it in Doric, Tuscan, or Corinthian; of one or two stories, an attic, Mansard gables? Here you are! At your service!”

“Two frontier lines”

In Cities of the American West, Reps deals with many of the same issues that he handled in his earlier major works. One topic, though, is new: the frontier.

In 1893, at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, Frederick Jackson Turner, a young historian, made a name for himself when he pointed out that, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the nation no longer had a frontier — that, except for scattered gaps, small and large, settlement had filled much of the West. As a result, he argued, the first phase of United States history had come to an end. No longer could Americans, uncomfortable in their present location, simply pick up and move ever westward to new and possibly more amenable surroundings.

As Turner saw it, the pioneers led the way, and the town-builders came later. But, as Reps shows in his 827-page book, that’s not what happened.

The town-planners were, he asserts, the spearheads of human settlement in the wilderness. Communities would be plotted and planned, and organizers would do whatever they could to entice settlers to their sites. The lucky ones succeeded. Indeed, Reps writes:

“In the American settlement of California, the Pacific Northwest, and Utah, the western frontier had leaped over the Great Plains, and by the middle of the nineteenth century there were in reality two frontier lines.

“One pushing slowly eastward from the Pacific Coast, while the other extended along the western borders of Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas. Shortly after midcentury, this older frontier line would once again begin to advance.”

Until, finally, by 1890, the two lines had come close enough to each other that they ceased being lines.

Real estate speculators, religious leaders, railroads, mining companies and, in most cases, the street grid had drawn pioneers from the eastern half of the nation and from the Pacific coast, and had filled in what had once been a vast wilderness.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.3.20

This essay/book review originally appeared in two parts in the Third Coast Review on 6.4.20 and 6.11.20.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.