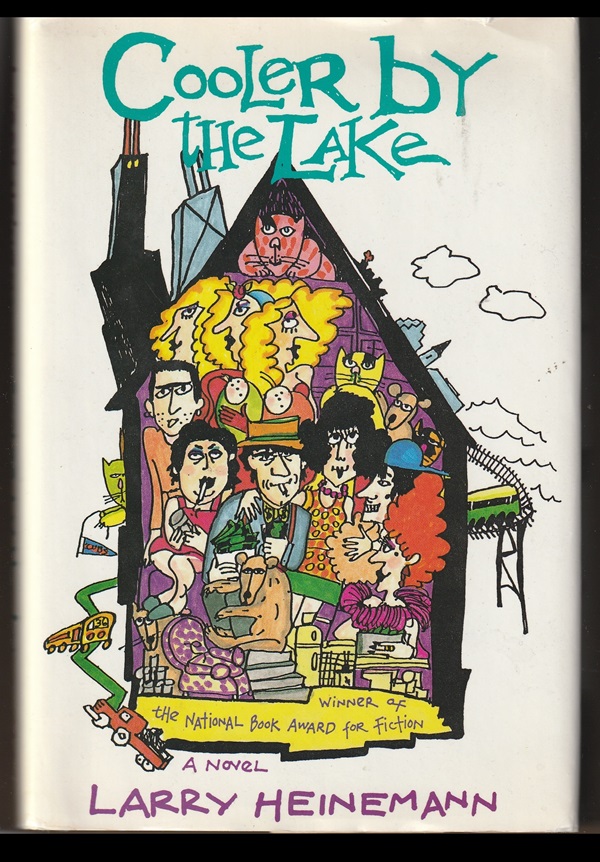

I wanted to like Cooler by the Lake by Larry Heinemann. It is so saturated in Chicago. Yet, it doesn’t hang together. It is a string of sometimes witty, sometimes flat sentences, scenes, characters, observations, incidents and shards of history that never cohere.

I had the thought, as I read the book, that Heinemann may have been aiming at a new way of writing a comic novel, that he may have been trying to create a mosaic of Chicago life at a particular moment in time, 1989, when the second Mayor Daley, Richard M., was just taking office. A mosaic that would have the most minimal of central images and instead be made up of dozens of sentences, scenes, characters, observations, incidents and shards of history. A novel virtually plotless.

After all, Heinemann taught creative writing for much of his life at Columbia College in Chicago, at the University of Southern California and at Texas A&M. So he may have had an idea of breaking new literary ground.

And Cooler by the Lake is certainly unusual inasmuch as very little happens. Instead, much of the space on the pages is taken up by various characters and Heinemann’s narration ruminating about and commenting about stuff that, at some point in the past or the future, had happened or might happen.

Indeed, it is as if, instead of telling a story, Heinemann was trying to cram every Chicago-ism, every Chicago quirk, every unique element of Chicago into his novel, including this quote from Mike Ditka about George Hallas as his epigraph:

“He threw nickels around like manhole covers.”

“Mildly incompetent, mostly harmless”

The novel opens with a description of the character who, for better or worse, carries the weight of the story, what there is of one:

Maximillan Nutmeg was a mildly incompetent, mostly harmless petty crook, always hustling for money. He would wake up in the middle of the morning, listening to the traffic coasting through stop signs at the corner, and run easy dough “Max makes a million” schemes through his head.

He’s also, I’m afraid, only mildly amusing and mostly directionless which makes him difficult for the reader to hang out with for 241 pages.

At some point while reading Cooler by the Lake, I got the idea that Heinemann may have envisioned Max as the personification of Chicago — not one of those ambition-crammed New Yorkers, not one of those laid-back Los Angeles sunglass-wearers, but instead a real guy, i.e., someone like you and me, which is to say, someone who doesn’t do much in the course of a day or a week and who, in truth — alas — isn’t very interesting.

Obviously, I guess, Heinemann thought Max was interesting enough to carry the book.

“Named after”

Also not very interesting, at least much of the time, was the way Heinemann would mention a Chicago street and immediately interrupt his narration to say who or what it is named for. At first, this was simply irritating. But, as he continued to do this throughout the book, I came to think that it was part of his strategy to portray Chicago as a mosaic, with each street being a set of related tiles.

Here, for instance, is one example:

All the rest of the morning and into the afternoon he worked his way up State Street to Lake Street, then over to Dearborn (named after General Henry Dearborn, veteran of Bunker Hill, and President Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of War) and down to Van Buren (named for the President), over to Clark and up as far as the Greyhound Bus station across Randolph Street (for some obscure reason named after Thomas Jefferson’s cousin John Randolph, Virginia’s U.S. Senator in the 1820s), from Richard J. Daley Plaza, kitty-corner from City Hall — a building that looked like a mausoleum or a World War II Maginot bunker — stopping strangers and passersby and hustling them with his sad tale of cheerful incompetence and once-in-a-lifetime woe.

That, if you’re counting, is one sentence, interrupted three times for the street name background. And there would have been a total of five interruptions except, by this point (page 42), Heinemann had already given the etymology of State and Lake Streets.

Actually, if you read that sentence and enjoyed it, then Cooler by the Lake is for you. That sentence is the novel in a microcosm.

Here and gone

Heinemann’s reference to the Greyhound Bus station on Randolph is an example of another major element of the novel — his mention of dozens of places and things that dotted the Chicago landscape in 1989.

Heinemann’s reference to the Greyhound Bus station on Randolph is an example of another major element of the novel — his mention of dozens of places and things that dotted the Chicago landscape in 1989.

Indeed, at this remove, 33 years after its publication, the novel provides an indication of how much Chicago has changed in a third of a century.

For instance, here are items that can still be found today in the city:

- The Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) Howard Street elevated train yard

- The Walgreen’s at Granville and Western Avenues

- The Thorndale el station

- The George B. Swift public grade school at 5900 N. Winthrop Ave.

- The Number 22 Clark Street CTA bus

- Gethsemane Garden Center, 5739 N. Clark St.

And here are the items that are now gone:

- The Salvation Army resale center at Clark Street and Bryn Mawr Avenue

- The State Street mall

- Payphones

- The Zayre discount store on Clark Street near Touhy Avenue

- Cap’n Nemos sub shop at 7367 N. Clark St.

- Kroch’s and Brentano’s bookstore in the Loop

- Merrill C. Meigs Field, a single-runway airport on Northerly Island adjacent to downtown (until it was bulldozed overnight in 2003 by Mayor Richard M. Daley)

- The Dominick’s grocery store chain

- The Greyhound Bus station on Randolph

Our neighborhood

A close look at both of those lists shows another aspect of Cooler by the Lake — how much of it takes place on the Far North Side of Chicago in the neighborhoods of Edgewater and Rogers Park.

That, in fact, is another reason I wanted to like the novel.

At the time Heinemann wrote the book, he and his wife were living in the 1700 block of Granville Avenue, between Hermitage and Ravenswood Avenues. Eight years earlier, in 1984, my wife and I had moved into the 6200 block of Paulina Street, about a block and a half from the Heinemann home. (I never met him, but my wife was a neighborhood acquaintance with his wife.)

Maximillian Nutmeg lives just south of Peterson Avenue on Ravenswood across from the Chicago and North Western Railroad commuter line embankment, in other words, about three or four blocks from the author’s home (although at some point he moved away and, in 2019, died in Bryan, Texas) and five or six from our house (where we still live).

So, for me as a neighborhood resident, there was a good deal of fun reading about Heinemann’s characters moving around in my turf.

But not that much fun.

Angst and bravado

I’m not sure what non-Chicagoans would make of this novel. But, for all its aimlessness, Cooler by the Lake has a lot of stuff that will resonate with people who live in Chicago — and, I mean, who really live in the city and aren’t the sort of people who, when travelling, will say they’re from Chicago even though they live in Burr Ridge.

For instance, here is Max being faced with the need to drive to Northfield:

Drive out there? By myself? Out into the great shit-stomping, mock-wholesome, holier-than-thou suburbs? The land of cheesy mortgaged-to-the-hilt condominiums, subdivisions of “single family homes” and thistle prairies, commercial zones and snarling traffic, and brain-dead, Goody Two-shoes solid citizens as far as the eye can see — the slums of the twenty-first century?

There is a certain amount of true-to-life Chicago angst and bravado contained there.

“Rhyme with”

And here’s another true-to-life Chicago-ism in the novel, an oft-told joke that reflects a rather coarse aspect of the city’s humor:

“Hey, Max, got a joke for ya,” said Oscar. “Name three Chicago streets that rhyme with vagina. Give up?”

Max always gave up when Oscar came calling.

“Paulina, Melvina, and Lunt! Haw, haw, haw. Ain’t that a hoot?” (Melvina was named for the town of Melvina, Wisconsin; Lunt was named for Stephen P. Lunt, one of the estimable partners of the Rogers Park Building and Land Company.)

This is on page 112. Already, many pages earlier (on page 14), Heinemann had explained where the name Paulina came from:

(Paulina Street was named after the venerable and capricious wife of real-estate developer Reuben Taylor…)

Haw, haw, haw.

Patrick T. Reardon

2.6.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.