About a third of the way into Elmore Leonard’s Cuba Libre, Victor Fuentes, a secret revolutionary, asks Amelia Brown to pass along information about the rich planter who pays her bills and enjoys her company.

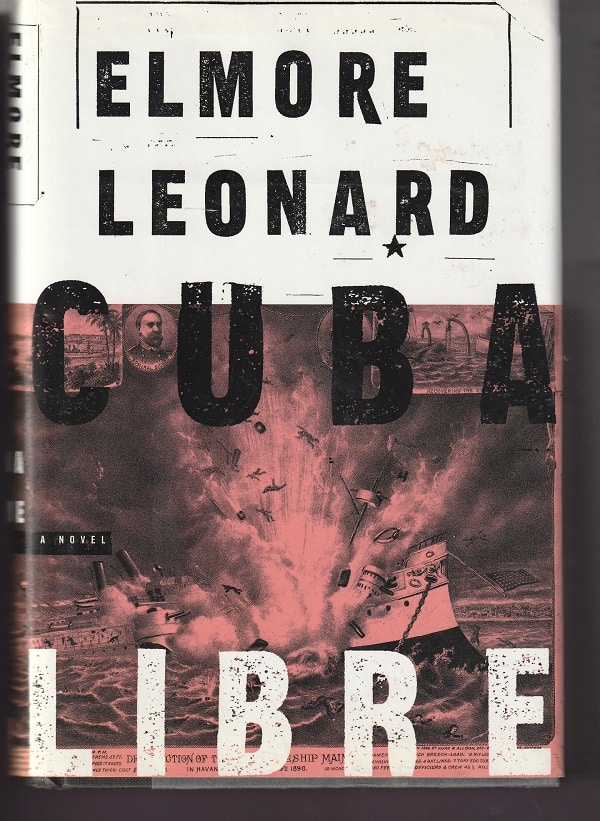

This is Cuba, early 1898, in the days after the explosion of USS Maine battleship in Havana harbor, setting the stage for the Spanish-American War. Amelia’s rich planter is Roland “Rollie” Boudreaux. Both are Americans. Fuentes is Boudreaux’s mulatto right-hand man — and also the half-brother and co-conspirator of Islero, one of the major insurgent leaders, fighting to expel the Spanish.

“You’re asking me to spy for the mambis,” Amelia tells Fuentes. His response:

“I see you not very busy, so I wonder, what is the point of you?”

That question — what is the point of Amelia? — is at the heart of Cuba Libre (Free Cuba in English), published by Leonard in 1998, a century after the events in the book.

“A small black spot”

It is true that you could argue that the novel is really about the complicated conflict in Cuba where the native population have been working for decades to drive out their European overlords and where the United States has economic interests — such as the sugar plantation of Boudreaux — that it wants to protect and expand.

This means there’s a lot of working at cross purposes in the story, a common occurrence in a Leonard novel.

And, if you wanted, you could insist that the book is really about Ben Tyler, a typical Leonard hero, a Texas cowboy/bank robber/ex-con with a quiet confidence and a pleasant personality except when crossed. The 31-year-old Tyler has come to Cuba to deliver some horses to Boudreaux who doesn’t want to pay full price for them — and, initially unbeknownst to him, to deliver arms in the hold of the boat to the insurgents.

Well, to deliver arms to sell to the insurgents. No one in this novel, except maybe Clara Barton, founder of the Red Cross, who puts in an appearance, is completely altruistic.

Especially not the Spanish officers in the novel who tend to be showy and prideful and more than a bit touchy.

When one of them, Teo Barbon, slaps Tyler to initiate a duel with him, the cowboy knocks him nearly off his feet with a left to the face. And then what? Rant and rave?

No, what Teo did, he drew a short-barrel pistol from inside his suit — a .32, it looked like — extended the weapon in what must be a classic dueling pose in the direction of Tyler, barely more than six paces away, and while he was taking deliberate aim, intent on an immediate finish to this business, Tyler pulled a big .44 revolver from inside his new alpaca coat and shot Teo Barbon in the middle of his forehead. My Lord, the sound it made! And there, you could see the bullet hole like a small black spot, just for a moment before Teo fell to the floor.

In moments, Tyler is escorted out of the bar by Spanish troops and to a dreaded prison — not for killing Teo (although that certainly didn’t help) but because another officer, Lionel Tavalera, believes that Tyler smuggled guns into the country with his horses and wants to find the boat in order to prove his suspicions.

“Ropes around their necks”

Yes, the Tyler part of the story, which becomes in part a battle of wits with Tavalera, is pretty interesting.

But Tyler spends most of the novel mooning for and then enjoying the attention of Amelia while Tavalera doesn’t trust her and, at every turn, it seems, gets her attention by shooting someone unarmed, including a leper with elephantiasis.

For instance, on an earlier occasion at a train station, the Spanish troops have two guys in custody —

small men…with big mustaches, yes, in heavily soiled clothes and shapeless straw hats…bareheaded, hands tied behind them, ropes around their necks, the ropes looped over beams that supported the platform’s wooden awning.

“A chance of making a mistake”

The Spaniards, led by Tavalera, think the two men are insurgents, but Fuentes tells Boudreaux and Amelia that he doesn’t think they are. Nonetheless, the soldiers want to hang the men but can’t figure out a way. Tavalera tells the two Americans that he’s sure the men are rebels.

Tavalera started to turn, but stopped as Amelia said, “What a minute,” amazed that Rollie was letting it go. “Victor’s just as sure they’re not insurgents. There must be a way to resolve this kind of situation. Isn’t there?”

“Yes, of course,” Tavalera said. “What we say is, why take a chance of making a mistake?” He turned from the window, motioned his men out of the way as he approached the two prisoners, removed the ropes from around their necks and placed the men one in front of the other, as though to march them off the platform. Now he drew his revolver and shot each one, bam bam, like that, in the right temple.

If you’re familiar with Elmore Leonard novels, you’ll know that Tavalera is one of the many amoral but not completely unattractive sociopaths who play large roles in many of his stories.

“Short of losing it”

So, in Cuba Libre, you’ve got the typical Leonard hero (Tyler) and the typical charming and almost appealing coldblooded killer (Tavalera) and a lot of people working at cross purposes.

Even so, this is Amelia’s book about her efforts to determine what is the point of her.

Is she someone who floats through her youth with the likes of Boudreaux? Or someone who works at a leper sanctuary? Or a revolutionary? Or a double-crossing conspirator? Or a gun-wielding killer? Or the marrying kind?

“I wanted to do something with my life. I mean short of losing it; I’m not a martyr.”

That’s what she tells Ben at some point in the middle of their adventure. Or would it be more correct to say, at the start of their adventure?

Patrick T. Reardon

5.25.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.