In 1937, Agatha Christie published Death on the Nile in which her detective Hercule Poirot has to solve a whole bunch of puzzling murders while on a river steamer cruise. A year earlier, in The Arabian Nights Murder, John Dickson Carr trotted out his detective Gideon Fell to figure out how a dead body found in a museum, holding a cookbook, came to be there.

These mysteries, also called whodunits, were emblematic of what has been called the “Golden Age” of detective fiction between the First and Second World Wars. Often the story involved some element of a locked room in which a murder victim is found. And always the heart of the story was the puzzle that the all-knowing detective had to solve.

There were a great many conventions to these stories. Indeed, Monsignor Ronald Knox, a Catholic priest and mystery writer, even came up with the Ten Commandments of writing detective fiction. (Example: The criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to know.

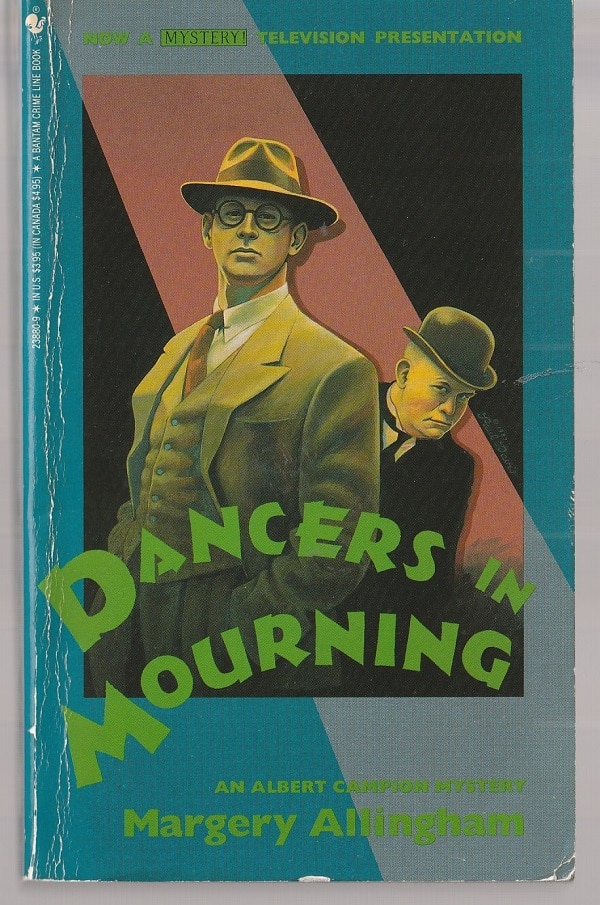

Margery Allingham, however, wasn’t following anyone else’s rules when, in 1937, she published Dancers in Mourning.

“UnPoirot-ish”

Yes, there is a twist at the end when the reader discovers who the killer is, actually a couple twists, but here are some of the ways in which Allingham writes this mystery in her own manner:

- Her amateur detective Albert Campion has some clever moments in the course of the story, but, in the end, it’s the cops who discover the killer, and Mr. Campion is as surprised as anyone.

- Instead of peopling her novel with a lot of self-satisfied rich folk, Allingham makes it a mystery about theater people, all of them edgy as a matter of personality, and even the most successful of them is not in any way comfortable.

- White Walls, the suburban home where most of the people live or visit, is not the isolated mansion of the usual whodunit. Indeed, the characters are often flitting back and forth to nearby London.

- One minor character in the book is a six-year-old named Sarah who develops an unlikely and truly delightful friendship with an oversized former crook.

- Allingham offers a puzzle, but the plot of finding a solution takes a back seat to her development of the characters. Mr. Campion, in fact, “felt himself chained to a very slow avalanche. Sooner or later, today or tomorrow, it must gain impetus and roar down in all its inevitable horror, breaking and crushing, defeating and destroying.” How unPoirot-ish can a sleuth get?

- And, probably the most surprising, Mr. Campion falls in love early on with the wife of someone knee-deep in the mystery, suffers from the pain of his beloved’s unavailability and spends much of the novel trying to keep away from White Walls despite the entreaties of people there and the police.

“It was fearful”

There’s a daintiness to many of the mysteries of the 1930s, a carefully fostered sense of unreality to the situation and the characters, the better to make it easy for the reader to take in one murder after another as pleasurable plot twists rather than, well, a killings.

Allingham is in no way dainty.

Consider the plot twist that occurs two-thirds of the way through the book and it involves one of the characters at White Walls being killed in an explosion that also takes the lives of two other men, injures five women, three children and seven men and shatters two hand trucks of milk cans.

A police investigator is telling Mr. Campion about the incident:

Oates was genuinely moved. “I went down myself last night and took a look at the place. Then I went on to the hospital and the mortuary. It was fearful. The mess was terrible. Women cut about with glass, you know, doctors digging splinters as long as my fingers out of them. The men who were killed were in a frightful condition. [One man] had a piece of metal blown clean through his head. It had dug a furrow you could put your wrist into clean through the top of his scalp. And the poor porter chap! I won’t make you uncomfortable with a description. They got a steel nut out of his stomach.”

His pleasant dry voice ceased but he kept his eyes on Campion’s own.

“It was fearful,” he repeated. “I’m not a squeamish man myself but the sight of that milk and blood and glass everywhere upset me; it made me feel sick. A very extraordinary and dreadful thing altogether,” he finished with a touch of prim severity.

No, Allingham definitely isn’t dainty.

At home in a Dickens novel

So, she’s got a detective who is far from the perfect investigator, and she’s not at all fussy about describing murder in a way that resembles the real thing.

All of this makes Dancer in Mourning a breath of fresh air, but, even better, Allingham fills the novel with a host of secondary characters who would be right at home in a Dickens novel.

Such as the next door neighbor of White Walls who pays a visit at a most inopportune time for the residents (but a wonderful time for her future gossip-mongering):

Mrs. Paul Geodrake came into the room as if it were a fortress she had stormed. She was a fresh-faced, red-haired woman in the mid-thirties, smartly if not tastefully dressed, and possessed of a voice of power and unpleasantness unequaled by anything else Campion had ever heard. It occurred to him at once that the fashion for well-dressed stridence was out of date. Also he wished that she were less determinedly vivacious.

And such as Renee Roper, who answers the door when Mr. Campion is doing a little sleuthing at the lodgings of the first murder victim, Chloe Pye:

The woman was not entirely unexpected, in type at any rate. She was small and brisk, her hair elaborately dressed in an old-fashioned style and her silk dress enlivened at neck and elbow with little bits of white lace….

She came out to look up at him, and the light from the street lamp opposite the gate fell upon her face, showing it to be small and shrewd, with bright eyes and a turned-up nose which had been much admired in the nineties.

“A Georgian tough”

And one last example: The 79-year-old Dr. Bouverie who drives up to several of the White Walls folk as they stand in the dark near the body of Chloe Pye on the roadway:

Campion never forgot his first glimpse of the figure who climbed slowly out of the darkness of the car into the tiny circle of light from the torch. His first impression was of enormous girth in a white lounge suit. Then he saw an old pugnacious face with drooping chaps and a wise eye peering out from under the peak of a large tweed cap. Its whole expression was arrogant, honest, and startlingly reminiscent of a bulldog, with perhaps a dash of bloodhound. He was clean-shaven except for a minute white tuft on his upper lip, but his plump, short-fingered surgeon’s hands had hair on the backs of them.

A Georgian tough, thought Campion, startled, and never had occasion to alter his opinion.

More savory

Dancers in Mourning is not a book with a plot that will keep you turning the pages furiously.

Its pleasures are quieter and more savory. And its pleasures are many.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.21.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.