Helen Shiller — a longtime radical activist and the new alderman in Chicago’s 46th ward — turned 40 on November 24, 1987. Two days later, she went to City Hall for an 11 a.m. meeting with the man who was something of a mentor to her, Harold Washington, the city’s first Black mayor. And she writes, “As I entered the main entrance to the mayor’s office on the fifth floor of city hall, all hell seemed to break loose.”

In a tense, vivid paragraph three-quarters of the way through her memoir Daring to Struggle, Daring to Win, Shiller tells of Washington’s secretary running out to the front desk, speaking frantically into a phone and running back to the inner office. Two Department of Health doctors and a paramedic, carrying a stretcher, ran down the outside corridor to the side entrance of that inner office, and then:

Moments later, Alderman Dick Mell came smashing through the front door, which had been closed moments earlier by Ernie Barefield, Harold’s chief of staff, who came out to tell me the mayor had collapsed. Mell, a proud member of the Vrdolyak Twenty-Nine, was gleeful, almost giddy, as he accosted Ernie and demanded to know if the mayor was alive or dead.

Ah, the sheer rawness of Chicago’s visceral politics in that moment.

Aldermanic lapdogs

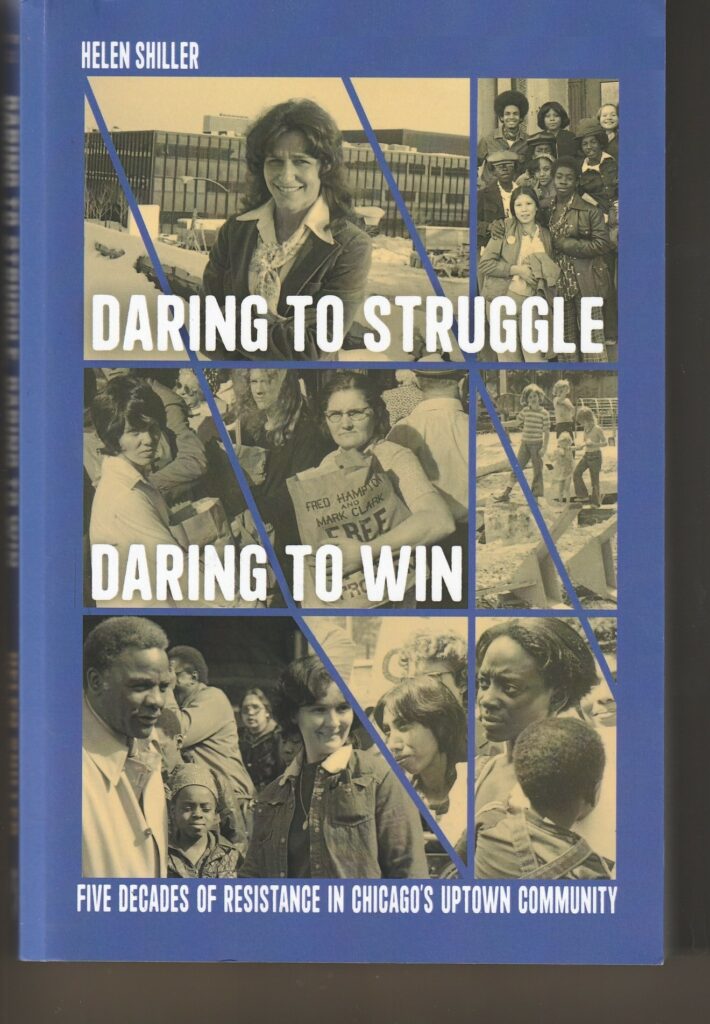

Shiller’s Daring to Struggle, Daring to Win, with its subtitle Five Decades of Resistance in Chicago’s Uptown Community, is an important book about Chicago, its politics and its people.

It chronicles a period in the history of the Chicago City Council when its fifty aldermen — male or female, they were all called aldermen — were the lapdogs of a series of powerful mayors.

Throughout much of the second half of the 20th century, mayors — Richard J. Daley, his successor Michael J. Bilandic and the Old Man’s son Richard M. Daley — also held direct or indirect control of the Democratic party. They used this political dominance to keep the council members in line and hold a tight grip on all citywide decisions, particularly finances. Smart and loyal aldermen would be given the chairmanships of key council committee where they exercised at times substantial delegated power.

In return, aldermen were autocrats in their wards with closely protected prerogatives over such issues as zoning and housing. Most used this authority to take care of the needs of middle-class homeowners, the most enduring bloc of voters, as opposed to transient apartment dwellers. This made reelection fairly easy — and corruption as well. Indeed, 25 present or former aldermen were convicted of official crookedness during a 26-year period.

This power dynamic was temporarily shattered when the progressively minded Harold Washington at the head of a coalition of African Americans and Latinos, won the mayor’s office in 1983.

Two ambitious aldermen, Ed Vrdolyak and Edward M. Burke, took advantage of the racial animosity among white Chicagoans — and of the reality that, under city law, the council was technically stronger than the mayor — to organize a rebel group of 28 whites and one Hispanic, known as the Vrdolyak 29. In what became nicknamed “Council Wars,” this group took control of all council committees and did everything it could to hamstring Washington’s efforts as mayor.

The battles ended in April, 1986, when the last of seven court-ordered special elections was won by a Washington ally, giving the mayor majority control of the Council.

A year later, Washington solidified his hold on power by defeating white candidates in the primary and general elections and, incidentally, helping Helen Shiller narrowly win her third attempt at the 46th ward aldermanic seat. And, immediately, the old power dynamic began shifting back as members of the white rebel group, including Dick Mell, pledged their loyalty to the African American mayor.

Such pledges, though, were reflective of Washington’s new political power, not of any acceptance of him and his agenda — as Mell showed with his “gleeful, almost giddy” response to word of the mayor’s collapse.

Unique perspective, unique voice

This is the world of Chicago politics that Helen Shiller describes from her unique perspective and in her unique voice in Daring to Struggle, Daring to Win, and it’s her uniqueness that gives the book its greatest significance.

When Shiller arrived in Uptown in 1972, as an activist committed to working to improve the lives of those on the margins of society, using as a blueprint the Black Panther Party’s Ten-Point Program, Shiller found herself banging heads with the deeply entrenched system.

And not just Shiller. She was a member of a core group of dedicated iconoclasts, many of them graduates of the radical 1960s and most of them white, who saw their role in the Far North Side Chicago neighborhood as helping people of color, immigrants, people in poverty, people battered by the hard knocks of life to get a fair shake from the schools, the police, the full range of city government. As she writes:

When I had first arrived in Chicago, Uptown had a legacy of social services. While the Intercommunal Survival Committee and later the Heart of Uptown Coalition interacted with them, our focus was to create programs in the community by and with the people most affected. We were focused on “survival pending revolution” and organizing for the change we sought. However, people often turned to existing private and public institutions and social service agencies for help and assistance. There were times when we found these programs lacking or disrespectful, and we were not shy about saying so.

Survival, revolution and resistance

“Survival” is a word that Shiller uses often in the first half of her book when she is talking about her efforts as an activist lobbyist and protestor and as a partisan journalist — efforts aimed at ensuring that each person had what was needed to survive.

Her use of the word “revolution” is also telling. The work of the Heart of Uptown Coalition was deeply countercultural. It was, as her book’s subtitle says, about “resistance” — about defying and battling the power structure of a deeply inequitable city and American society.

Shiller writes that her book is the story of her growth and development “as I tried to be a soldier in the class and race struggles the United States faced in the second half of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first.” This was not the attitude of the average member of the Chicago City Council.

“To fight for a just and fair city”

As she was setting up her new aldermanic office in City Hall, one of Washington’s council allies “put his arms around my shoulder, bent down, and whispered in my

ear, ‘Now that you’re here, it’s time to go along to get along.’ ” In other words, now that you’re here, “Make no waves.” As if.

I wasn’t elected to “make no waves”; I was elected to fight for a just and fair city where all voices are heard, where development could occur without displacement, and institutional racism and institutional corruption would be challenged and addressed.

Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, whom Shiller and her allies knew before he was killed in a 1969 police raid, was a key inspiration for their work with people on the margins. Although the young and shy Shiller initially had no thought of becoming a politician, she knew that Hampton had said, “Politics is nothing but war without bloodshed, and war is nothing but politics with bloodshed.”

And the title of her book is from something Hampton once said, “If you dare to struggle, you dare to win. If you don’t dare to struggle, you don’t deserve to win.”

“Bureaucracy busters”

This was the attitude that Shiller and her allies brought to their non-violent war on behalf of the people of Uptown who were outsiders in their own neighborhood.

Whereas the typical Chicago alderman and typical city worker would give priority to the needs and wants of property owners and business owners, Shiller and her allies had a preferential option for the poor.

It was an approach that also became a hallmark for her as a City Council member:

When I became alderman, I had a mantra that my staff and I were “bureaucracy busters,” meaning our job was to advocate for our constituents with the bureaucracies of government, break through their roadblocks, and get results — especially when we were told that our requests were not possible.

“Persona non grata”

During her near quarter-century as an alderman, Shiller was never in danger of being mistaken for a run-of-the-mill City Council member. She was a thorn in the side of the Democratic regulars, and, although she had progressive colleagues at times, none was as identified with “the struggle” as she was. (By contrast, today, there is a Democratic Socialist caucus of five aldermen in the Council.)

In her book, Shiller asserts that she was never “the lone voice against Daley [the younger] and what remained of the machine.” But then she acknowledges that the image arose because, in each year from 1995 through 1999, she cast the only vote against the mayor’s budget.

Unlike every alderman, except the finance committee chairman, Shiller actually read the budget — line by line. She would sit down each year with the new proposal and go through it item by item and prepare hundreds of questions for city officials about plans and program.

It was tedious work. And the party-aligned alderman did everything they could to block her. “I was a persona non grata,” she writes, and adds this story:

For many years Daniel Alvarez was the commissioner of the Department of Human Services. Of Puerto Rican descent and fluent in English and Spanish, he developed an extremely thick accent (making it difficult to understand what he was saying) whenever he didn’t want to answer a question—which included most of those I posed to him. I had to work around him.

A life of resistance

Shiller had to work around a lot of people to get things done, but, from 1987 through 2011, she found ways to do that, both in providing services to her ward and in raising questions in a governmental body that doesn’t like questions.

She was dogged in her work as an alderman, and, in writing Daring to Struggle, Daring to Win, she is dogged in detailing what seems like every initiative and campaign she worked on as an activist and every issue and battle she dealt with as an alderman.

Hers is not a book for light reading. It documents a life of resistance, a life of struggle.

It is an important record of late 20th century Chicago, and a sort of blueprint for how a rebel can challenge the power brokers and maybe not completely reshape society but at least win myriad small victories for people who have no one else to fight for them.

.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.7.22

This review initially appeared at Third Coast Review on 11.15.22.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.