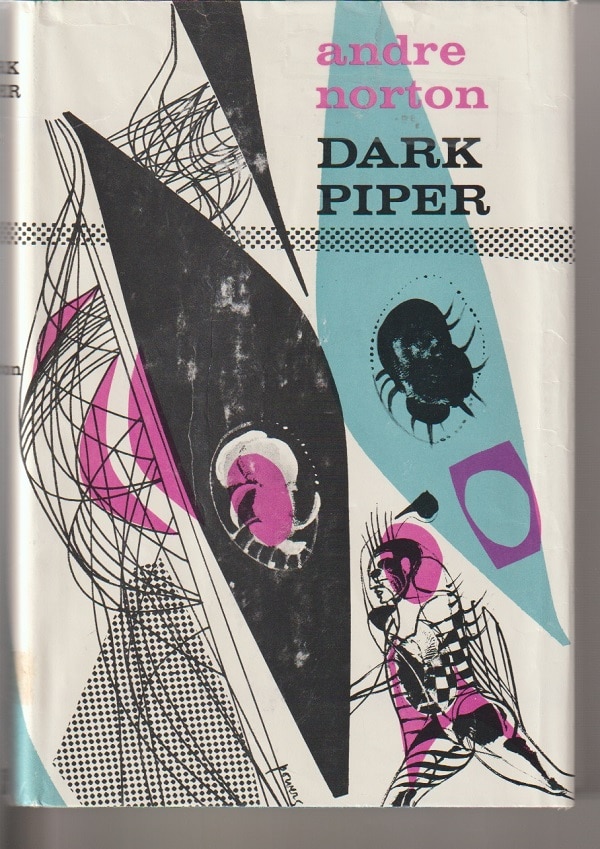

Dark Piper, one of Andre Norton’s best novels, tells of the twisting-turning odyssey taken by teenager Vere Collis and nine younger companions across and under their planet’s landscape, an expedition from normal life to a fight for survival amid a seemingly endless array of new dangers and challenges.

In fact, the dangers and challenges never do come to an end.

The title of this 1968 book refers to the one adult who helps these youngsters in their unexpected and arduous journey, Griss Lugard, a soldier injured in the ten years of galactic wars, newly returned to his home planet of Beltane to mine for ice-bound archeological artifacts.

He is called Dark Piper because, when most of the group meet him, he is playing a tune on a slender dark red pipe that captivates a bird known as a herwin and a small animal called a hanay.

He did not speak or hail us, but rather he raised the rod to his lips. Then he began to pipe — and at that trickle of clear notes, falling in a trill as might spring rain, the herwin whistled its morning call and the hanay rocked back and forth on his clawed digging paws, as if the music sent it into a clumsy dance.

I do not know how long we stood there, listening to the music that was like none I had ever heard before, but which drew us. Then Lugard set aside the pipe, and he was smiling.

The First and Second Laws

Often, in a Norton novel, a character such as Lugard would, throughout the story, pipe at various times, and the piping would be discovered to have a magical effect that would be of great use.

In Dark Piper, though, the pipe is broken and the piper killed early in the story, but not before Lugard has given a warning to the leaders of the small planet colony — that the ship of refugees seeking access to the planet aren’t to be trusted.

The leaders, some of whom are parents of the youngsters, are adamant, however, that, after so many destructive wars, they will adhere to their non-violent, open-hearted vision of how life should be. Indeed, their First Law was very clear:

“War is waste; there is no conflict that cannot be resolved by men of patience, intelligence, and good will meeting openly in communication.”

As was their Second Law:

“As we value life and well-being, so does lesser life. We shall not take life without thought or only to satisfy the ancient curse of our species, which is unheeding violence.”

“Wide frightened eyes”

The refugees aren’t so idealistic. They bomb some of the Beltane’s settlements and unleash a virus that wipes out the planet’s population.

Vere and the nine others escape because they’re on a field trip to see the caves where Lugard has started digging. Deep inside, they’re suddenly shocked:

There was a wave of vibration through the walls of the cave, in the solidified layers of lava under our boots, giving one the sickening sensation that the world had always accepted as solid was that no longer. I head a shrill scream and saw in the glow of a beamer wide frightened eyes and mouths opening on more cries of alarm….

A second shock came, even worse than the first. Lava chunks broke loose, rattling and banging. I cowered, deafened by the sound, while dust arose about us in choking clouds.

“Safest place”

More shocks followed. The teens and children initially think these represent earthquakes, but Lugard sets them straight — bombs. Who, one of the teens asks, would do such a thing? And Vere answers:

“The refugees. What chance—?”

He stops himself so as not to scare his younger friends any worse. Lugard tells Vere that he suspected and then knew such an attack would take place.

Then, why bring the youngsters in the caves?

“Because this is the safest place on Beltane — or in Beltane — here and now….There’s a shelter down here.”

“The rightness of right”

So the group begins heading to the deep underground shelter. After two hours, they rest, and, for the second time, Lugard takes out his pipe and plays.

And the magic he wove settled into us as a reassuring flood of promise. I could feel myself relaxing; my whirling thoughts began to still, and I believed again. In just what I could not have said but I did believe in the rightness of right and that a man could hope and find in hope truth.

Then, just as he finishes, Lugard realizes that a portion of the cave is about to collapse. “Back against the wall!” he yells, and then reaches out to save one of the youngest, asleep on a roll of blankets.

He succeeds but isn’t able to save himself.

“That could not be!”

The rest of the novel — three-quarters of its length — is devoted to an account of Vere and his younger companions coping with a wide array of dangers, including mutant animals, ravaging refugees and a booby-trapped world.

And, all the while, they are trying to determine whether many, or any, of their family, friends and other Beltane people have survived and how badly the bombs destroyed their community. Vere, the oldest, feels this the most:

Ten of us and a whole world — but that could not be! Somewhere there were — there must be — others! And in me the need to find them grew stronger until my impatience was such I longed to wake the company, to set out at once on the search.

The story of Vere and the others growing in responsibility, skill and daring is one of high adventure.

And one of belief in themselves, hope in the future and their willingness to look at the truth of their situation and to face everything that comes at them.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.13.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.