Near the end of his concise life of the Bible’s David, David Wolpe writes:

He is such a contradictory personality that even the ancient rabbis confessed: “We are unable to make sense of David’s character.”

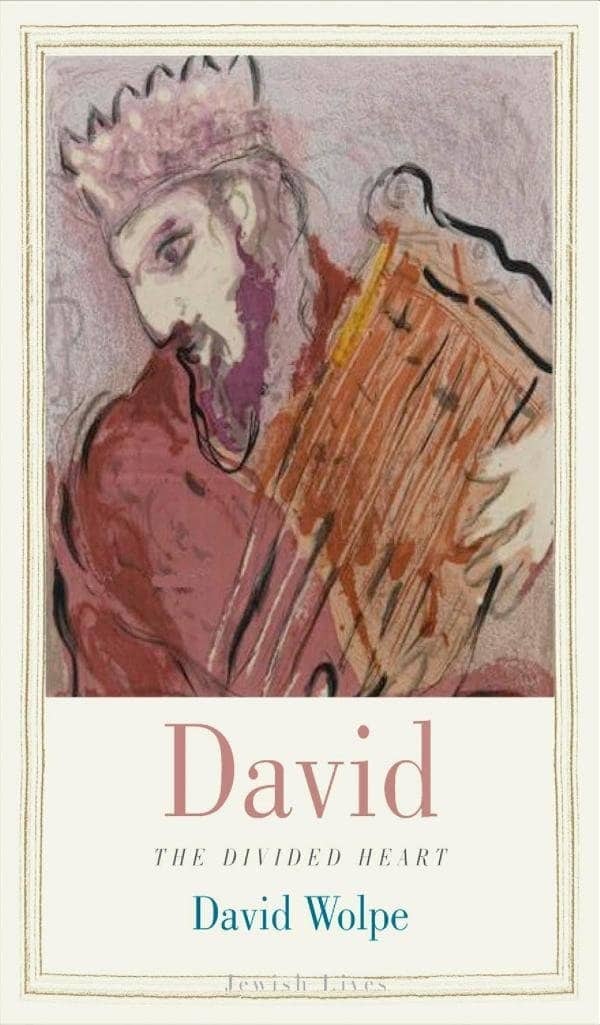

That’s a sentence that Wolpe, the senior rabbi at the Sinai Temple in Los Angeles, might have put on any page in his book, David: The Divided Heart, published in 2014 as part of the Jewish Lives series.

Indeed, Wolpe doesn’t even try to make sense of the character of the man.

David — who was, apparently, in some way, an actual historical figure — was a truly complicated guy. He was a believer, an adulterer, a murderer (by proxy), a shepherd, a poet/musician, an over-doting father, a poor excuse for a husband, a seemingly addled old man and a towering figure, not only in the scriptures of three major religions but in Western culture.

Wolpe notes that historian Baruch Halpern called David “the first human being in world literature.” And, after describing the slayer of Goliath and the putative writer of the Psalms as “the Bible’s most complex character,” he writes

[David] is the first person in history whose tale is complete and vital, laced with passions, savagery, hesitation, betrayal, charisma, faith, family — the rich canvas of a large life.

There are other firsts that Wolpe asserts at the start of the book. The bulk of David’s story is contained in 1 and 2 Samuel, and Wolpe writes that some scholars have described these two biblical books as “the first great work of history, the first biography really worthy of the name in a modern sense.”

The biblical writers who told David’s story were, Wolpe writes, artists of genius:

They left us an account of a warrior-poet-hero wily as Odysseus and tortured as Lear, yet as faithful as the “shepherd of Israel” (Psalm 78).

A complex Elijah

Begun in 2010 through a partnership of Yale University Press and the Leon D. Black Foundation, Jewish Lives is a series of biographies aimed at exploring Jewish identity from antiquity to the present. So far, more than 50 have been published, and many more are planned.

One recent addition was Becoming Elijah: Prophet of Transformation by Daniel C. Matt, an expert on Jewish spirituality.

Elijah, Matt writes, is elusive like ruah (wind, spirit) and often so filled with ruah that he becomes “zealous and stormy, unpredictable, restless.” Indeed, after Elijah has parched the land with drought and slaughtered his pagan idols as well as some relatively innocent bystanding soldiers, God decides that Elijah has gotten altogether too zealous and replaces him.

Nonetheless, God takes the prophet, while still alive, up to heaven in a fiery chariot, and, in his new role as a unique sort of angel, Elijah becomes compassionate, gracious and generous — fighting for justice, championing the innocent, healing the sick and heralding the salvation and the Messiah to come.

It’s a complex story to be told about a complex person, earthly and heavenly, and Matt makes Becoming Elijah lively, erudite and buoyant. As the 156 pages of his text and 38 pages of endnotes attest, Matt’s scholarship is deep, and his writing is nimble, entertaining and informative.

“Perfectly consistent”

By contrast, Wolpe shies away from grappling with the complexity of his subject. At every turn, he writes about how, on the one hand, some scholars say this about David while, on the other hand, some scholars say that.

One [expert] portrays him as a paragon of faith who fell but once, another as a Machiavellian villain who cannily rose to rule. Each has hold of a piece of what makes David so compelling. The drive to see David’s character as perfectly consistent betrays a blinkered view of human nature.

Wolpe is creating a paper tiger when he argues that it’s wrongheaded to attempt to find “perfect” consistency in David’s actions. Serious biographers recognize that their subjects will act in tortuous and, at times, inconsistent ways.

Consider the complexities of such historical figures as Napoleon, Elizabeth I, Oliver Cromwell, Thomas a Becket, Andrew Jackson, Robert E. Lee and Lyndon B. Johnson. Even the Great Emancipator, Abraham Lincoln, had a complicated jumble of views on African Americans and slavery and carried out an array of actions that, at times, were at cross purposes.

Yet, over the centuries, biographers have told the stories of such figures, working to find and give a sense of what made them tick as human beings. That’s the job of a biographer.

David in sections

However, Wolpe is much more comfortable discussing the debates and disagreements of commentators concerning each aspect of David’s life. For him, David is a deep mystery, ungraspable.

That leaves the reader with a bad case of either/or and he-said/she-said and with the job of guessing the answer to the key questions: Who was David? What made him tick?

One aspect of Wolpe’s aversion to taking a stand on the character of David is his decision to break his story into eight discrete chapters: young David, lover and husband, fugitive, king, sinner, father, caretaker and death.

Instead of endeavoring to see David in the round — think of Michelangelo’s sculpture — Wolpe wants to examine the biblical figure in sections. He doesn’t want to consider how, for instance, the young David relates to the fugitive David, or how David as father relates to David as sinner.

Faulkner, Leonard Cohen and Shakespeare

Wolpe’s pretty glib in mentioning the many works of literature that have to do with David, such as these:

- David, a little-known play by D. H. Lawrence.

- The John Dryden poem “Absalom and Ahitophel.”

- Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner.

- God Knows by Joseph Heller.

- An early, unfinished play by Bertolt Brecht.

- King David by Alan Massie.

- The King David Report by Stefan Heym.

- Leonard Cohen’s song “Hallelujah.”

He also likes to compare David with other great literary figures, particularly those of William Shakespeare. For instance, Wolpe writes:

Did the tropes of David’s story influence Hamlet? How much Shakespeare borrowed from the biblical David is impossible to say. (Henry V bears striking thematic resemblances as well.)

Later, he describes the scene in which Saul consults the Witch of En-Dor, or ghostwife, as “full of the intrigue of Macbeth by way of Stephen King.” And, in one of the final sentences of his book, Wolpe writes:

David stands like Lear on the heath, the epitome of earthly experience, raging, beset, the one who feels most deeply, the one who has God’s heart.

Vitality and feeling

However, unlike Heller, unlike Dryden and Faulkner and the others, Wolpe isn’t working to figure out what made David tick.

Of course, any reading of this complex guy will be imperfect, any description of who he was and what moved him to do what he did will be faulty. But generations of scholars and writers have tried it, nonetheless.

They knew they’d fall short. But they also knew that, in trying, they were helping their readers get to know and understand David, however incompletely.

Lear and Hamlet and Macbeth and Henry V are complicated characters, and, for over five centuries, actors, directors, playgoers, scholars and other writers have debated what made them tick.

The thing is: They did tick. Shakespeare wrote them in such a way that they were filled with vitality and feeling, and an aliveness that is communicated no matter who is playing the role or who is reading the text of the play.

By contrast, David is sapped of much of his vitality and feeling by the method Wolpe uses in his book. He doesn’t tick.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.19.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.