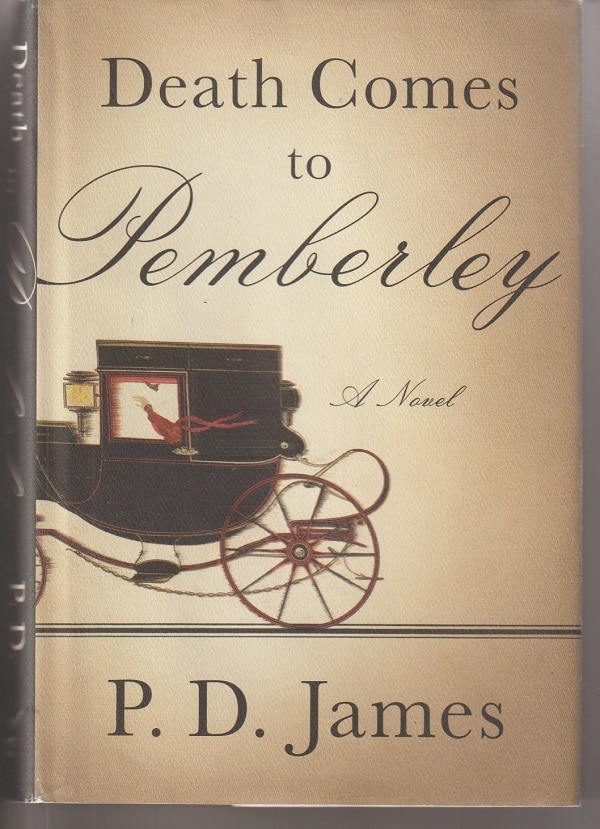

Technically, Death Comes to Pemberley by P.D. James is a pastiche inasmuch as it’s a literary work, written in the style of another author, in this case, Jane Austen, that celebrates Austen’s art.

I’d suggest, though, that, even more, it’s high-toned fan fiction. But maybe I’m just splitting hairs.

James was in her 91st year when, in 2011, she published Death Comes to Pemberley, her final book. Three years earlier, the 14th and last of her Adam Dalgliesh mysteries, The Private Patient, had arrived in bookstores.

Her celebration of Austen’s Pride and Prejudice was, it seems to me, an important book to her. It not only gave such characters as Elizabeth and Darcy (and Lydia and Wickham and others) additional life beyond the end of the Austen novel, published 198 years earlier, but also brought them into James’s own fictional world. (In addition, it gave her a chance in passing references to link the world of Pemberley to people from two other Austen novels Emma and Persuasion.)

My suspicion is that the James book may have been written earlier, even decades earlier, and only trotted out at the end of her life because, well, she wanted to pay her homage before dying.

She may have waited until the end of her career because she knew that many, many fans of Pride and Prejudice have very definite opinions about the characters, particularly the brooding Darcy, and that anyone venturing onto Austen’s turf was running the risk of ticking off a whole lot of readers.

Also, because, I think, James recognized that Death Comes to Pemberley isn’t great James nor is it great Austen.

She wanted, in my view, to publish it anyway because she was a fan.

A fun, engaging read

Let me quickly say here that the novel is a fun, engaging read, especially for fans of Austen and fans of James. Indeed, I think that someone with no previous knowledge of James’s books or of Austen’s would also find it enjoyable.

The thing is that melding Austen’s world of social jockeying, clearly delineated rules of manner and strict class gradations with James’s world of bloody murder and painstaking detection is more than a bit awkward. There are demands on both sides that need to be met, and that ain’t always easy.

For instance, James has to start with a set of characters whom she did not create.

On the technical level of writing, she encountered a minor problem in the fact that two of the characters — Darcy and his cousin, Colonel Fitzwilliam — are named Fitzwilliam. Austen didn’t have much of a problem with that since Darcy was always called Darcy. But, to show the closeness of the married couple’s relationship, James has Elizabeth address her husband as “Fitzwilliam” during a conversation.

As a result, in Death Comes to Pemberley, the other cousin must always called Colonel Fitzwilliam or simply the Colonel. If James had created these characters, the cousin could have been Colonel Something-else.

The killed and the killer

On the level of character and plot, I suspect it was out of the question for James to involve any of the beloved Pemberley people and their families and friends as either the killed or the killer in her novel.

Again, Austen fans would have gone ballistic if, say, Darcy had been the victim or if Elizabeth’s sister Jane had been the murderer. (This is not giving anything away since James makes clear early on that almost all of these people had alibis.)

True, George Wickham, the ne-er-do-well husband of Elizabeth’s ditzy sister Lydia, is the one charged with the murder — the victim is his friend Captain Denny — and the tension in the book is whether he will be convicted of the crime. And, of course, whether he actually did it. (He did, after all, say, “I killed him.”)

But Wickham has been a known scoundrel since about a third of the way through Pride and Prejudice, so, if anyone from that novel would be acceptable as the bad guy in Death Comes to Pemberley, it’s him.

Not that I’m saying it’s him. (Or not him.)

To present and solve the problem

As a mystery novelist, James has to supply the slaying that needs to be solved and the detective or detectives who are solving it — and a puzzle that pulls the reader along to the revelation at the end.

To do this, she provides a bunch of new secondary characters who, because of the focus on the Pride and Prejudice crew, don’t get much time on stage but are essential to the mystery. Even the main detective Sir Selwyn Hardcastle appears on few pages, overshadowed most of the time by Elizabeth and Darcy. Indeed, most of the novel is told from the point of view of the two spouses.

The upshot is that the solution is pretty jury-rigged, built on coincidence, hidden facts and a deus ex machina. So, as I say, Death Comes to Pemberley isn’t great James.

To present and solve the problem, James has to deal in a very direct way with the sort of facts that don’t find much place in Pride and Prejudice, such as specific times of day, the details of the legal system, the lives of the lower classes, suicide (twice), illicit sex and a war in Ireland.

What that means is that many pages have a very un-Austen feel to them and that the James book isn’t great Austen.

“Pretty enough”

Even so, in what might be described as a losing battle, James fills her book with much that is delightful and well-observed.

For instance, the opening pages of the book in which James summarizes and advances the original Austen story does a good job of capturing the earlier author’s style:

It is generally agreed by the female residents of Meryton that Mr. and Mrs. Bennet of Longbourn had been fortunate in the disposal in marriage of four of their five daughters…A family of five unmarried daughters is sure of attracting the sympathetic concern of all their neighbors, particularly where other diversions are few, and the situation of the Bennets was especially unfortunate.

These Meryton ladies were amazed when Elizabeth Bennet snapped up Darcy for a husband, a stunning development since “Miss Elizabeth’s triumph was on much too grand a scale.” Indeed, as James explains:

Although they conceded that she was pretty enough and had fine eyes, she had nothing else to recommend her to a man with ten thousand a year and it was not long before a coterie of the most influential gossips concocted an explanation: Miss Lizzy had been determined to capture Mr. Darcy from the moment of their first meeting.

That’s James at her must Austen-like.

“Protracted dying”

Later in the novel, Elizabeth is recalling how the overbearing Lady Catherine de Bourgh accompanied her on a visit to a seriously ill young man in a worker’s cottage on the Pemberley grounds. On the way back to main house, the older woman opined:

“Dr. McFee’s diagnosis should be regarded as highly suspect. I have never approved of protracted dying. It is an affectation in the aristocracy; in the lower classes it is merely an excuse for avoiding work….

“The de Bourghs have never gone in for prolonged dying. People should make up their minds whether to live or to die and do one or the other with the least inconvenience to others.”

That wonderful quote — “I have never approved of protracted dying” — seems to me to be James at her most Jamesian.

“Negligible impact”

Elizabeth was shocked when she heard this comment since just three years earlier Lady Catherine’s only daughter had died after years of bad health. The mother, “after the first effusion of grief, controlled but surely genuine,” was quick, writes James, to regain “her equanimity — and with it much of her previous intolerance — with remarkable speed.”

Then, about the daughter, James notes:

Miss de Bourgh, a delicate, plain and silent girl, had made a negligible impact on the world while she lived and even less in dying.

That’s a line, I think, that could have been written by either Austen or James.

As imperfect as Death Comes to Pemberley is, I’m glad James wrote the book. It did give me a while to live again with all of that Pride and Prejudice community (and, guilty pleasure, I admit, in a cockeyed way, I liked reading again about the wild and goofy Lydia).

And, even though the plot points and character requirements don’t fit together smoothly, there is more than enough here of James and her novelist’s storytelling skill to make the reading of the book fully worthwhile.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.5.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.