It’s the awkward ones that touch me most — the images of an agitated Mary responding to the arrival of the angel Gabriel with the message that, if she consents, she will become the mother of Jesus, the Mother of God.

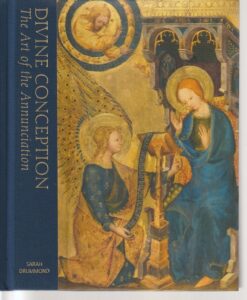

In her 2018 book Divine Conception: The Art of the Annunciation, Sarah Drummond presents a panoply of 121 full-color, richly reproduced images of this essential moment in Christian history.

These are from the first fifteen centuries after the life of Jesus, and Drummond groups them together in twelve thematic chapters, dealing with such topics as the visible presence of the Christ Child, the setting, what Mary was doing at the time Gabriel appeared and her response.

While all, even the most primitive, display great beauty and reverence, some resonate more deeply with this 21st-century believer, and those are the ones in which Mary seems disturbed, confused, even shocked by what’s taking place.

In mid-turn

Chief among these is the last image in the book, a painting by Lorenzo Lotto from around 1535, filled with energy and action.

Mary, in the bottom left corner of the work, seems to have been startled and almost on the point of running away.

To the right is a muscular dark-green-winged angel who appears to have just landed — indeed, he is still moving forward as if at a run — with his arm up and his eyes wide open, communicating, at once, the requirement of an answer as well as gentle compassion for the young women.

Between Gabriel and Mary is a large brown cat clearly spooked by what’s going on.

Meanwhile, in the upper right corner, an expressive God the Father leans forward strenuously, in an echo of the angel’s stance, with his hands clasped together prayerlike, as if he’s about to dive into the moment, or maybe send the Spirit or Jesus from between his hands.

Meanwhile, Mary, despite the twist of her body — away from the devotional book she was reading and praying with, away from Gabriel — Mary isn’t running away.

She seems to have stopped in mid-turn.

She seems to have heard Gabriel, and to have recognized what is happening, and to have realized the responsibility she is to be given, and to have realized the unknowingness of it all, and to have felt, viscerally, the joy and dread of bringing a baby into the world, the son of God, no less, and to have glimpsed in a flash the power she will unleash in her own life and in the world — and she seems, look at her hands, to have decided, yes, okay, I don’t fully understand, but I accept.

Our Magnificat

Our Magnificat

This is a very human response and one I can relate to.

It touches on the deep mysteries that we humans confront all the time and the questions we must face and answer, such as:

How should I live my life? Why choose to do good? To do what’s right? Why risk? Why not play it safe?

It’s a reminder that annunciations happen to all of us all the time. Each of us is asked:

Will you do this? Will you carry Jesus? Will you carry and live out the message of Jesus?

Each of us is asked to say our Magnificat.

As if to block a physical blow

A similarly contorted image of Mary is in the famous Annunciation by Simone Martini, created in 1333.

For all its opulent gold leaf — and something like 80 percent or more of the surface of the altarpiece shines with gold leaf — it presents a Mary who, twisting away from Gabriel, seems to be almost cowering from his message.

She is raising her right shoulder as if to block a physical blow. Her right hand is at her throat in a protective gesture. Her eyes are slit, her mouth is turned down.

Considering no

To be sure, it is difficult at this distance of nearly 700 years to know what the people of Martini’s time saw in Mary’s face here. Bodily signals of inner emotion vary from one culture to another, and from one age to another.

Still, it seems to me that Mary is reacting to her knowledge of the difficulties of what is being asked of her.

She seems to indicate feelings that I envision myself feeling if I were in her place — i.e., that this is an intrusion in my life, that I don’t want to sign on for the work and responsibility that will be required, and that I don’t want to give up control of my life to raise and let go a baby who is the Son of God.

I think, looking at this image, that it captures a moment when Mary — not the docile, meek Mary of many devotional pictures, but a Mary who has a strong sense of self and a strong will — is considering the idea of saying no.

That may sound like blasphemy, but think about it: The stronger Mary is as a person, and the stronger the pull she has toward living the life she had planned and expected for herself, and the more she is tempted to reject God’s offer — all of this means that her ultimate “Yes” is that much richer, deeper, more resplendent and holy.

Magnificent images

Drummond’s rich book is filled with other magnificent and thought-provoking images. Here are three:

Annunciation, by Fra Angelico, about 1445.

Annunciation, miniature from the Islamic ‘Jami’al-Tawarikh by Rashid al-Din (The History of the World), about 1307, believed to be the only image of the Annunciation in an Islamic manuscript.

Annunciation, by Rogier van der Weyden, about 1445

The next moment

I respond to that beauty and magnificence, but, still, I respond most to Mary’s agitation.

That inner turbulence, as well as elegance, is on display in the second to last image on Drummond’s book, Annunciation by Sandro Botticelli, about 1490.

Of all the images of this moment that Drummond provides in her book, this, I believe, is the only one in which Gabriel is coming in bent so low, as if he were a defensive back about the tackle Mary.

He’s so low because Mary is bent so much and her head is lowered almost to the horizontal, and Gabriel has to get as low as possible to make eye contact with her.

He is reading out with his right hand, but Mary is using both hands in a stately gesture that, for all its elegance, is akin to a running back about to stiff arm a tackler.

Perhaps a better description is that, like a dancer, her body, in every way, is exhibiting her desire not to be caught in this divine embrace.

But then, look at her face.

Mary is thoughtful. She is self-contained.

Even as she evades Gabriel’s message, she is pondering it.

And we know what happens in the next moment.

Behold, the handmaid of the Lord; be it to me according to your word.

And, later:

My soul magnifies the Lord.

My spirit has rejoiced in God my Savior.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.16.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Pat, I didn’t know you reviewed this book, nor did I know the book exists! Love your review!

Did you know that I have been an annunciation collector for a long time?

I am going to take pictures of them and show you!

Hang on!

I’m interested to see them.

I do not agree at all with you and the author about the Islamic “Annunciation .“

To me it is so clearly the Woman at the Well.

The water, the jug, Jesus obviously asking her for something. I wonder if there was a mistranslation?

Actually, I wrote a poem about my take on the scripture I refer too. I will look for that too!

I’m no expert, and the author has an extensive end note about the image. Also, I found a story here about it: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/opinion/2018/04/27/sacred-mysteriesthe-koran-mary-annunciation/. Also, there’s this: https://books.google.com/books?id=XUyajzkDJ50C&pg=PA295&lpg=PA295&dq=%22annunciation%22+rashid+al-din&source=bl&ots=Cqc-l3w-c6&sig=ACfU3U3f_tpbl0MSsxV3uoRVxKzYiJU3RQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjVjYSM5Z_oAhVKSK0KHTbcBV0Q6AEwBHoECC8QAQ#v=onepage&q=%22annunciation%22%20rashid%20al-din&f=false