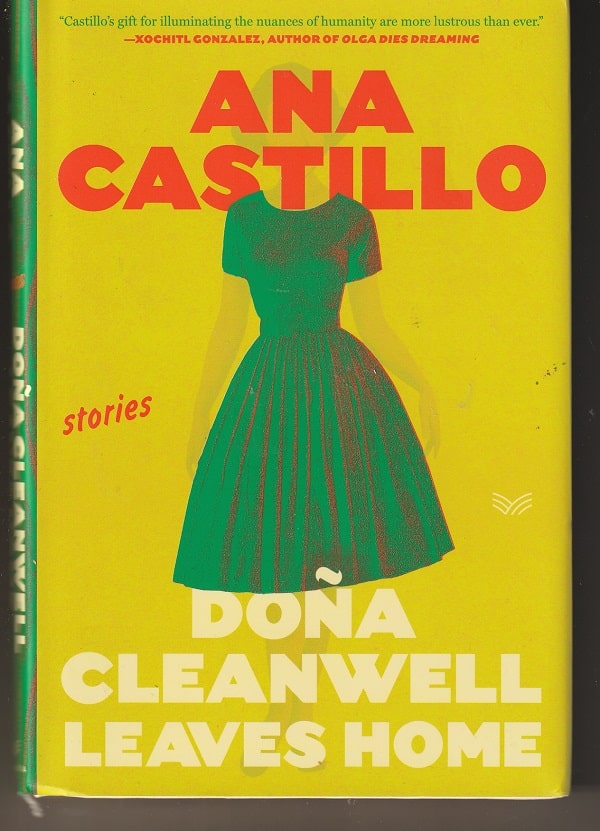

In the seven stories in Ana Castillo’s new sparkling, gritty and compassionate collection Dona Cleanwell Leaves Home, there are a lot of common themes. Ghosts, for one, including a beautiful naked woman who walks through a party in a Mexico City home.

And cleaning women, as the title of the book and its longest story suggest although, in the story, Dona Cleanwell isn’t a person, but the slightly garbled name of cleaning products from a company in England. And blue-collar workers.

Virtually all of the characters in this collection, published by Harper Collins, have Hispanic roots. Some are Mexicans who live in Mexico while others are Chicagoans who are linked to that nation if only by having family there. A few are from other places, such as Spain and Guatemala.

Another of Castillo’s themes is that many of these characters find themselves as outsiders. Such as in “The Girl in the Green Dress,” in which Vicenta, a new librarian at one of Chicago’s branches, is pestered by a yuppie-ish woman with a bike helmet about the supposed ghost of the title:

Whenever Vicenta had interactions with white people, she tended to stiffen. English was her first language, but not being looked upon as white, therefore not presumed “American,” and especially as a librarian, she felt pressured to use her best English.

Gringa?

The reverse happens to 18-year-old Katia in the “Dona Cleanwell” story. Her father’s originally from New Mexico while her mother’s from Mexico City. That’s where the teenager is sent to bring her AWOL mother home, and, while there, someone refers to her as a “gringa.”

“Why did she call me gringa?” Katia whispered to [a friend of her mother], who was nearby. She didn’t think she looked white. The thought suddenly occurred to her that perhaps only in Chicago was she considered Mexican. Ironically, in Mexico, she was considered a pocha.

Pocha is a derogatory term used by native Mexicans about people from the United States with Mexican roots but unable to speak Spanish.

Stealing a smoke

There are a goodly number of things that men do in this collection that are mean, overbearing, unfaithful and even criminal. But Castillo is much more interested in what her female characters do to deal with such oppression — in the way they cope with the strictures of a male-dominated society and the way they transgress them.

Such as sneaking a smoke while a husband naps.

That’s what one elderly mother does in “Tango Smoke,” digging out the pack and matches from between the arm rest and cushion of her sofa and sitting near an open window. She’s feeling wistful and introspective, recalling her long life, including the time in her native Spain when she was arrested for having obtained an abortion. Her family got her out of jail but urged her and her husband to leave the country.

She remembers watching her mother go to the polls when Spanish women first got the vote. She ruminates about women who have made a name for themselves, such as Jackie Kenney Onassis and Emma Goldman.

By the same token, there were women without ideologies and politics, out of the limelight and whose names not even the neighbors knew. These anonymous women went about their daily affairs quietly suffocating under the pressures of society’s expectations. On the sly, whether in retaliation against the status quo or out of desperation, they dared break the rules. These insurgents, in Cuca’s opinion, were the true heroines of each generation of women.

“In search of the Divine”

Better known as a novelist and poet, Castillo has published only one earlier story collection, Loverboys in 1996. In Dona Cleanwell, two of the stories have overlapping characters, but there are those threads that are woven through all seven: ghosts, cleaning people, outsiders and women who break rules on the sly.

These aren’t short stories with a punchline. Each one tells of complicated lives that, for the characters, are often confusing. What I’m wanting to say is that there is a unity to these different scenes, and I think it can be traced to the opening page of the book, a prologue. The first sentence is: “It starts with the journey; as ever, whether Quixote or Kerouac, you are in search of the Divine.”

There is no God-talk in these stories. Yet, the ghosts are one hint about the deeper, more spiritual level of human life that Castillo is wanting to evoke.

Her characters — the women and the men, the children — are trying to cope with a life that is often overwhelming and bewildering, trying to get through the day, get through the hour without a roadmap.

The ant and the elm

In that prologue, Castillo writes, “We walk a good way on tiny legs and yet we’re so insignificant, we aren’t aware of being minutiae.” She notes that we humans like to think of ourselves as being in control. Maybe that’s so we don’t go mad — at least, that’s my reading of it. The final sentence of that one-page prologue is key:

Does an ant recognize the elm by the single root it so industriously scurries around?

Every one of Castillo’s characters — women and men — are ants scurrying around, clueless of the elm above, and the sky beyond, and the Cosmos off into infinity.

In her stories, she brings compassion for these clueless ants, knowing that their confused meanderings in life aren’t unique to them. She brings compassion, I think, because she knows that she and you and I are all clueless ants.

And we are each on a journey to the Divine — something we have no way of ever understanding or even recognizing, given how small and clueless we are. We’re searching for the elm although we can’t conceive of it.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.1.23

This review originally ran at Third Coast Review on 10.17.2023.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.