Noir fiction, like film noir, deals with bad guys doing bad things, often to each other.

So why do we care?

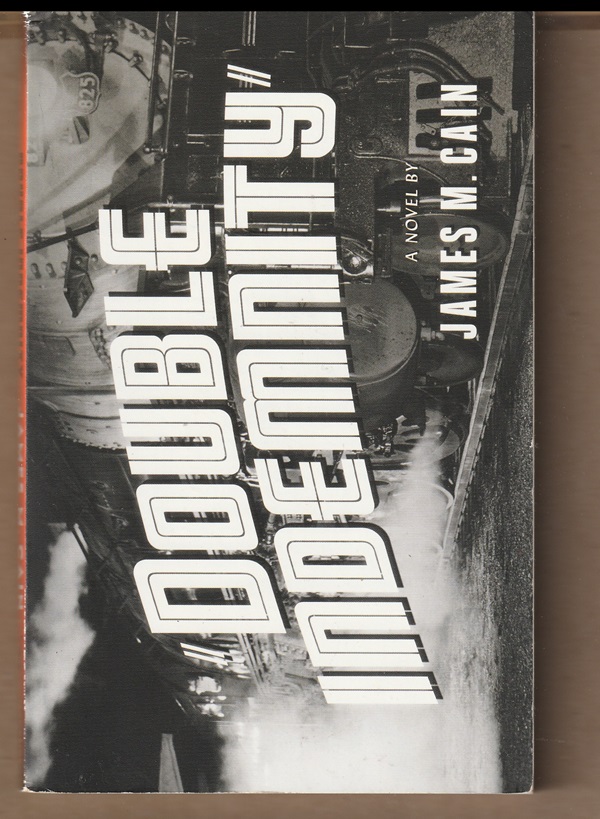

James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity — serialized in 1936 in Liberty magazine and published as a novel in 1943 — is a case in point.

The narrator of the story is Walter Huff, an insurance agent who gets lured by femme fatale Phyllis Nirdlinger into a plot to kill her husband. He realizes she’s on the make and recognizes that he should have nothing to do with her.

But he does.

So, saying she “lured” him is only part of the story. After 15 years as an insurance agent, Walter seems to have gotten bored, and he seems attracted by the idea of committing a perfect murder — indeed, he’s given it a lot of thought — and attracted by the idea of making a ton of money through insurance, and, yes, attracted by the vision of having Phyllis to himself when it’s over.

He’s attracted even though Phyllis makes clear at the beginning that she may not be the best of partners:

“Maybe I’m crazy. But there’s something in me that loves Death. I think of myself as Death, sometimes. In a scarlet shroud, floating through the night. I’m so beautiful, then. And sad. And hungry to make the whole world happy, but taking them out where I am, into the night, away from all trouble, all unhappiness…”

“Three essential elements”

Walter isn’t fazed by that. In fact, he’s excited and begins lecturing Phyllis about how to kill her husband:

Walter isn’t fazed by that. In fact, he’s excited and begins lecturing Phyllis about how to kill her husband:

“Get this, Phyllis. There’s three essential elements to a successful murder.”

He then explains that the first element is that you need help. You can’t do it alone. The second is to having everything planned in advance: the time, the place and the way.

“The third is, audacity. That’s the one that all amateur murders forget…There comes a time in any murder when the only thing that can see you through is audacity….

“Be bold. It’s the only way.”

And he goes on to say they need to be bold and go after the largest amount of insurance money they can get. Insurance companies, he explains, know that it is rare for anyone to die accidentally during a train trip, so they add to policies a feature to sweeten the deal, a promise to pay “double indemnity” for railroad accidents.

They will, Walter tells Phyllis, murder her husband in such a way that it appears to be a railroad accident, and they will collect $50,000. In present day terms, that’s the equivalent of $1.1 million.

“As long as I lived”

And so they do.

And, after they do, Walter is suddenly afraid and aware of the hole he’s in.

Then I started to think. I tried not to, but it would creep up on me. I knew then what I had done. I had killed a man. I had killed a man to get a woman. I had put myself in her power, so there was one person in the world that could point a finger at me, and I would have to die. I had done all that for her, and I never wanted to see her again as long as I lived.”

This occurs at the halfway point in the novel, and the second half is taken up with the efforts of Walter and Phyllis not to be discovered.

And, in the end, they get their comeuppance.

“Why do we care?

Walter and Phyllis are unattractive people. Phyllis may be slinky and sexy, but, as the story evolves, it’s clear that her husband wasn’t her first victim. Walter is a self-deluding, small-time schemer who’s running scared.

So why do we care? Why do we, readers, gobble up a book like this? And an entire genre of noir novels and films?

The answer, I believe, has something to do with the alchemy of storytelling. Cain’s novel has been popular for many decades, and that’s because he makes his narrator, Walter Huff, out to be a regular sort of human being.

In the opening pages, Walter sounds like just an average guy telling a story. Not every writer can create a “voice” in this way, but Cain certainly can. And Walter’s “voice” is recognizable enough that the reader quickly relates to him.

The reader is going through Walter’s day with him, and, in a way, the reader is doing what Walter is doing and is thinking what Walter’s thinking.

The reader is hooked

In this way, the reader is hooked, and, by the time Walter starts to go south morally, the reader cares enough about Walter and wants to know what’s going to happen.

In addition, the reader, like Walter, is attracted to the idea of a perfect murder — not a real-life murder, but a make-believe one in the pages of Cain’s novel. The reader keeps going in order to find out how it will happen and then what the result will be.

I suspect, too, that a story of crime and wrongdoing may give the reader a thrill of taking part in something that the reader can’t and won’t do in real-life. The noir novel lets the reader forget the moral code of everyday existence and pretend to be willing to do bad things.

Finally, every reader has made mistakes. Every reader has done bad things, usually very minor things, such as driving too fast or fudging tax returns.

Reading Double Indemnity, the reader knows how Walter feels to have made a decision and carried out an action that went wrong. For the reader’s own mistakes, the consequences are much milder. For Walter and Phyllis, they’re risking their lives.

No matter how much the reader may have bolloxed up some aspect of life, the blunders of Walter and Phyllis are clearly much worse. And that may be, in some way, consoling.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.25.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

I need an online PDF for this book