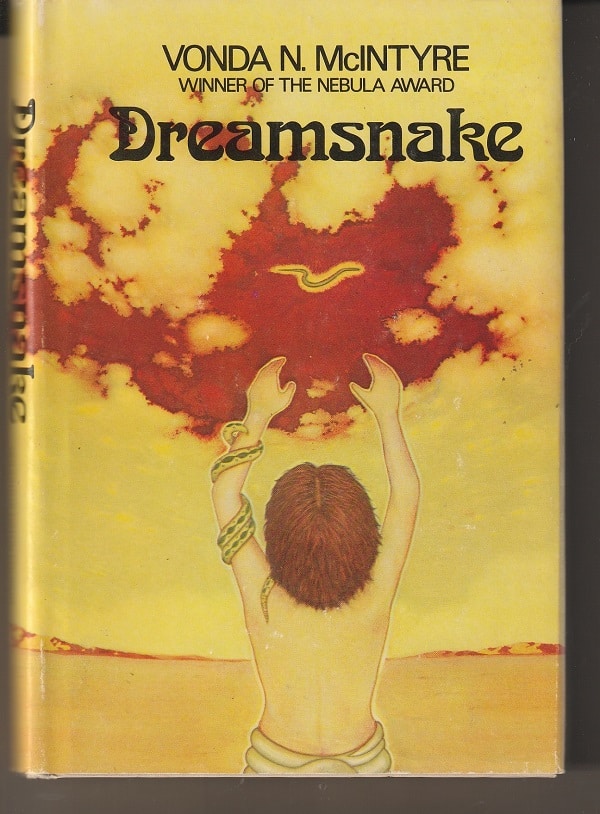

The culmination of Vonda N. McIntyre’s 1978 novel Dreamsnake comes in the final pages when the healer woman Snake confronts North, the dark presence of the story.

It is a time long after nuclear war, and life on earth has gone back to the basics of survival for most people. Mutations are common, and some areas are still deadly radioactive.

From her training, Snake employs a genetically engineered rattlesnake and cobra to treat sick and injured people as well as a dreamsnake whose bite provides dreams that ease the pain of those who are dying. But, in the opening chapter, her dreamsnake is fatally cut by a superstitious nomad.

Dreamsnakes are from some other world, and they’re hard to replace. Throughout much of the novel, Snake is on a mission to find another one.

Her travels lead her eventually to a hidden jungle where North has “set himself up as a minor god” by using dreamsnakes as a drug to enslave followers as addicts. For reasons that aren’t immediately clear, North has dozens of dreamsnakes. And he has no desire to share them with healers such as Snake.

Like many a fictional villain, North is described as physically repellent:

The courteous tone remained, but behind it lay great pleasure in its taunting, and the man’s smile was more cruel than kind. His form was eerie in the dim light, for he was very tall, so tall he had to hunch over in the leafy tunnel, pathologically tall: pituitary giantism, Snake thought.

Emaciation accentuated every asymmetry of his body. He was dressed all in white, and he was albino as well, with chalk-white hair and eyebrows and eyelashes, and very pale blue eyes.

In most adventure stories in books and movies, when the confrontation with the villain takes place, the hero gleefully, righteously, triumphantly crushes the bad guy to the cheers of the audience.

But not in Dreamsnake.

“Guilty of arrogance”

When North asks for peace, Snake won’t consider mercy. She is filled with a deep desire for revenge because North inflicted dozens of dreamsnake bites on her daughter Melissa, leaving the girl in a coma and near death.

Now, Snake is threatening him with the bite of a dreamsnake. But, then, she has a realization:

Her pleasure in his capitulation turned to revulsion. Was she so much like him, that she needed power over other human beings? Perhaps his accusations had been true. Honor and deference pleased her as much as they pleased him. And she had certainly been guilty of arrogance.

Perhaps the difference between her and North was not of kind, but only of degree. Snake was not sure, but she knew that if she forced this serpent on him now, while he was helpless, whatever differences there might be would have even less meaning. She stepped back, dropping the dreamsnake to the ground.

A humanist adventure

Dreamsnake has been described as feminist science fiction, but that seems too constricting to me. I see it as humanist adventure — that is to say, an exciting story about a human being interacting with other human beings.

In her efforts to subvert the usual male-fashioned expectations of the adventure genre, McIntyre isn’t aiming to create a new bias.

True, there are some despicable men, such as Melissa’s supposed guardian, an abusive blacksmith, but there are many men who are admirable to one degree or another, including Arevin, the nomad who crisscrosses the landscape in search of Snake.

And, yes, every woman in the novel is strong, competent and attractive.

But this isn’t a novel asserting that women are better than men. Instead, it’s about a world in which a hero, at the moment of triumph, can second-guess herself, can recognize her failings.

Countercultural

It’s a world in which violence isn’t the answer. Indeed, Snake’s role as a healer involves finding non-violent ways to make people feel better. Her power is used for the common good, not to gain and hold control.

It’s also a world in which sexual relations take place on an equal footing, often in a casual manner. Which isn’t to say that sexual abuse doesn’t happen, but, when it does, it is all the more shocking.

And it’s a world in which men don’t have a monopoly on important jobs. The leader of Arevin’s tribe, for instance, is a woman. Healers are men and women.

Dreamsnake was a countercultural novel in 1978. Today, more than four decades later, it’s still radical.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.18.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.