The story of French noblewoman Marguerite de La Rocque de Roberval has been told and retold over the past 150 years in popular entertainment — several historical novels, poems, a biography, a short story, book chapters, a play, two television shows and at least two folk songs — and it’s easy to see why.

For one thing, this really happened.

In 1541, her relative Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval, a noble-born pirate, was sent by King Francis I to become Lieutenant General of New France or, as it was starting to be called, Canada. At some point in the journey across the Atlantic, Roberval, a strict Calvinist, became upset with Marguerite, apparently because the young unmarried woman had taken a lover (something difficult to hide during a months-long voyage in a small ship).

At an island in the New World — thought to be a place now called Harrington Harbour in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in far northeastern Quebec Province — he sent her ashore with her lover and her handmaid and sailed away. Both of her fellow castaways died, as did the baby to which she gave birth.

She was eventually found by Basque fishermen and taken back to France where, for a period, she was something of a celebrity.

“I felt alive”

So, the bare-bones record has a lot of elements to draw writers and readers. Even better, there are very few other facts that are known. Which means that this is a story that a writer can play with and create and shape to make a point.

It can, for instance, be fashioned as a Robinson Crusoe account of a young noble girl finding a way to take care of herself by herself and survive.

Or Marguerite can be portrayed as a pampered, whining twit who, through the rigors of her ordeal, finds her true self and grows to become a woman of power and fortitude. Or, from the start, she can be a strong-minded, take-charge dynamo. Or a plucky heroine, or a meditative hermit.

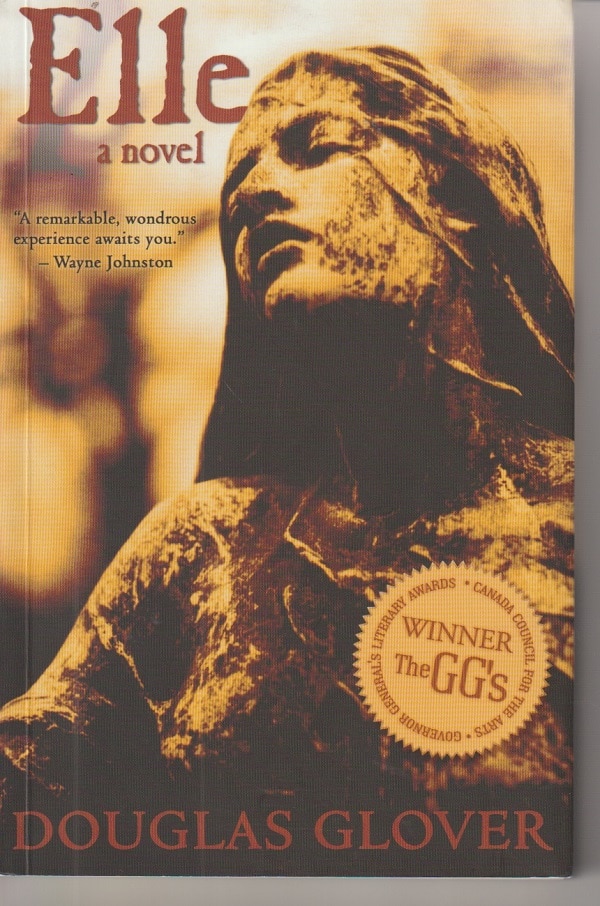

In his 2003 novel Elle (She), Douglas Glover envisions a Rabelaisian girl with a Gargantuan lust for life, even when she wants to die, and an openness to all the many alien things and people she encounters, a willingness to embrace the strange or, more usually, let the strange embrace her. A woman who finds herself living on the borders between the Old and New Old, between what she knew and what, in this foreign wilderness, she now knows. A woman who is overwhelmed repeatedly by the life she has to live in Canada, a place she calls the Land of the Dead, and yet….

This is strange — in the Land of the Dead, I felt alive, but here in France everything that was once familiar is like a coffin lid.

All this, and one other thing: Glover also sees the girl as Canada.

“Plagued by insects and ice”

Shortly after being marooned, the girl — who is never identified by the name of Marguerite in the novel — ponders her predicament and the place where she has been left to die or live and the people who have been sent by Francis to colonize the land:

Poor Canada, destined always to be on the edge of things, inimical to books and writing, plagued by insects in the summer and ice in the winter, populated by the sons and daughters of ambitious, narrow, pious, impecunious Protestants and inarticulate but lusty Catholic tennis players [her lover is a tennis player], not to mention the rest of the riff-raff on the expedition, drawn by the King’s order, from the prisons of Paris, Toulouse, Bordeaux, Rouen and Dijon — thieves, abortionists, frauds, panders, whores, footpads, assassins, along with the destitute and the witless, every kind of rogue except heretics, traitors and counterfeiters who were deemed unsuitable to the dignity of our pious enterprise.

The girl identifies herself as the first colonist in Canada. At one point, “amid the clarity of ice and sky,” she looks at the beauty of the landscape around her and finds a bit of warmth. But then:

This is a good moment which, as I might have guessed is really only a prelude to something worse. In Canada, I have learned the feeling good about oneself, entertaining hopes and plans, is a recipe for disaster.

“More mysterious and complicated”

Later, an old native woman with a tattooed face is taking care of the feverish girl who realizes that she is a strange creature to the woman — “as strange to her as she is to me.”

They have no way to communicate, and this oppresses the young woman, as it has earlier in the novel and will again many times. This inability to be understood or to understand is a caterwauling, confusing, maddening ordeal that she has to undergo. Nonetheless, she survives.

They have no way to communicate, and this oppresses the young woman, as it has earlier in the novel and will again many times. This inability to be understood or to understand is a caterwauling, confusing, maddening ordeal that she has to undergo. Nonetheless, she survives.

I think how alike any two strangers or lovers or friends are when they meet, that the point at which they meet is a place of confused identity, translation and dream, that we see only the parts we recognize, that we ourselves are only apprehended in this incomplete fashion.

She tells the old woman, “I am hungry.”

What I mean to say is that I am not myself, that since coming to Canada I have found the world infinitely more mysterious and complicated than I had hitherto supposed, that if she could only see me, speak to me, I might find myself again.

Later, in the middle of another chaotic attempt at communication, the girl says:

Since coming to Canada, all my conversations have been conducted anxiously in contending grammars, each describing a different world. What if all grammars are correct?

“The antiseptic and ghostly whiteness”

I suspect Glover’s Elle has subtle resonances for Canadians. The girl’s comments about the place aren’t all mordant.

When the ship arrives that will end up taking her to France, she knows that, in her return, she will become a spectacle for the curious and an item of entertainment. She, again, is caught between two worlds, and, in this state, Glover writes:

The sun is setting. Smoky lanterns blaze aboard the ship, which looms like a dark cloud or a sorcerer’s island. Just beyond her a whale breaches, rolling head to tail back into the sea. A cormorant, a black snake with wings, skims silently above the surface of the water. Eider ducks rise and fall on invisible waves. I am reminded of the mysterious beauty of Canada, peace just beyond the ambit of human squalor, silence split by the call of a bird or the cry of a wolf, the antiseptic and ghostly whiteness when winter comes. Already I miss the place.

Canada is a nation on the edge of things — on the northern edge of the globe, on the edge between Europe and the United States.

Its people know their nation’s imperfections and are reminded of them often by others. Like the girl, they long to be understood and heard.

At least, that’s how I read it from Glover’s novel.

“A headstrong girl”

Ultimately, in Elle, the girl is neither plucky nor a dynamo. She is, simply put, a survivor. A survivor like Canada.

And why does she survive?

The answer, I think, comes in the willfulness she exhibits throughout her earlier life and on the ship in the face of Roberval, the willfulness of a headstrong girl.

Just after she has been told that she is to be marooned, the girl ponders:

What do you do with a headstrong girl? Always a difficult question.

Kill her, maim here, amputate limbs, pour acid over her face, put out her eyes, shave her head, put her in a brothel or a nunnery, or simply get her pregnant and marry her. Better yet, maroon her on a deserted island lest she spread the contagion of discontent to other girls or even men, though men are generally impervious. Keep her away from shops and books and looking glasses and friends and lovers. Forget her.

This is the General’s solution.

“Headstrong” doesn’t mean strong. It means having a will and having an urge to live life on one’s own terms.

“Headstrong” doesn’t mean that the girl is in control of her life or the world around her. In a way, it’s the opposite.

The goal of this headstrong girl is to be herself wherever she is, and — if being herself means that she is marooned and means that she often finds herself in the midst of discordant tumultuous confusion — so be it.

She doesn’t cave in. She stays herself with all her bawdiness and pain and willfulness. And, if Glover has made this headstrong girl a metaphor for Canada, it is a compliment.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.6.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.