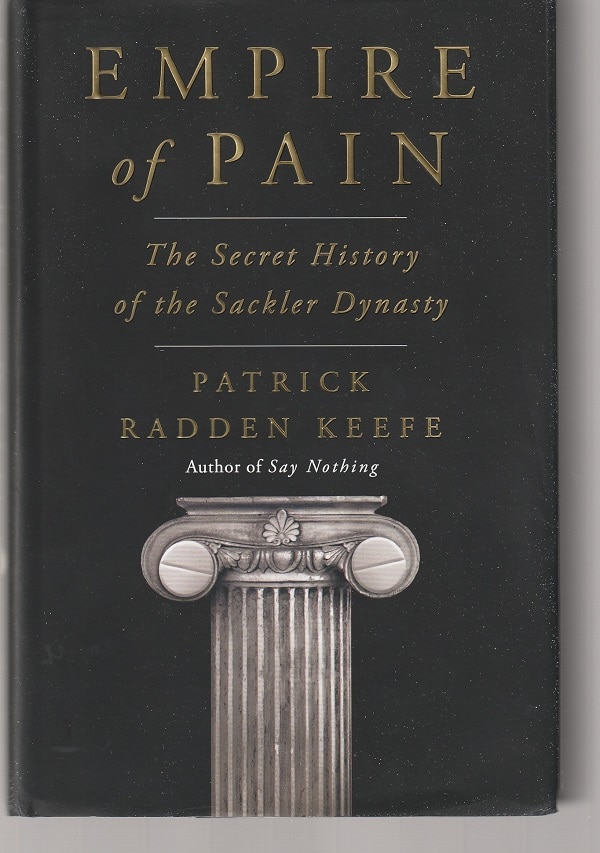

Two-thirds of the way through Patrick Radden Keefe’s 2021 Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty, I had to take a break.

I was sick and tired — and more than a bit bored — of spending so much time with the self-important, amoral and insanely rich Sackler family. So, I picked up and re-read Frank Cottrell Boyce’s endearing novel Millions.

It’s the poignant and hilarious story of a nine-year-old British boy name Damian who is an expert about saints — and even speaks with them. One night, from the sky, a very large bag lands at his feet, containing 229,370 British pounds, the equivalent of 323,056 euros.

This prompts a lot of greed-filled plot twists, but Damian, a sweet innocent if there ever was one, is at the center of that plot, and, in the end, he uses the money to help some needy people a continent away.

He’s no Sackler.

Skin crawl

Empire of Pain is the biography of a family, designed to make the reader’s skin crawl and blood boil, unless the reader is somehow related to a Sackler.

Keefe, building on two decades of news coverage, as well as his own research and interviews, depicts a family that amassed billions and billions of dollars in private wealth, mainly through the production and marketing of a drug — OxyContin — that led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

He writes about an immigrant Jewish couple in Brooklyn who gave birth to three brothers — Arthur, Mortimer and Raymond.

But it was the hyper-talented and endlessly restless Arthur, born in 1914, who took his younger brothers under his wing and set about making the family’s initial fortune, often by cutting ethical, moral and financial corners.

Known as philanthropists

After Mortimer and Raymond broke away from Arthur, refusing to share with him a sudden windfall, the next generation, mainly Raymond’s son Richard, built up Purdue Pharma as a cash cow through the production and sale of OxyContin, also cutting ethical, moral and financial corners.

For decades, Purdue claimed that various versions of OxyContin were eminently safe from abuse by the patients of prescribing doctors, despite the company’s own research and the mass of data that developed as an epidemic of opioid abuse swept the nation and became entrenched.

During this time, the Sacklers on Mortimer’s and Raymond’s side were intricately involved in the corporate decision-making and in reaping billions of dollars, routinely drained away from the company. Yet, for many years, their involvement was closely hidden.

The Sacklers were unknown to the vast majority of Americans, except those who were familiar with their many large donations to museums, schools and other institutions, always demanding that the family name be featured prominently.

Like a novel

Keefe writes well, and Empire of Pain reads like a fast-paced novel.

Indeed, for many readers, it will bring to mind the HBO series Succession which premiered in June, 2018, and features a business powerhouse patriarch, surrounded by often clueless family members and hyper-loyal aides.

With the Sacklers, the first-generation brothers, particularly Arthur, had a strong business skills and a fairly light feel for morality, enabling them to build enough of a fortune to set the stage of the creation and exploitation of OxyContin.

The second generation, though, as Keefe portrays them, come across as either lightweight air-head jet-setters or as meddlers in the Purdue Pharma business with the single goal of pushing the use of OxyContin in the U.S. and the world to the greatest extent possible in order to produce the greatest profit possible. Their children, the third generation, are shown to be more of the same.

Nothing redeeming

The Succession series — fictional but based on the ways immensely wealthy families tend to work — is offered to the viewer as a guilty pleasure. The major characters are arrogant, selfish, weak (or, in the case of the patriarch, ill), greedy, amoral and often ludicrous. The series offers catharsis for the viewer. It offers a group of people who, although gold-plated, are despicable. They may have more money that 99.99999 percent of us will ever see, but we can look down on them as being beneath our contempt. Except, of course, we do hold them in contempt.

Keefe accomplishes something similar in Empire of Pain. The cleverness of the first generation is deeply tainted by the moral and ethical corners the brothers cut.

The hyper-greed of the next generations is morally indefensible although the Sackler family, as detailed by Keefe, has sought for several decades to ignore the moral questions. Their response, as Keefe shows at every turn, has been to deny that OxyContin is responsible for the opioid crisis in the United States and to deny that, to whatever extent it might be involved, it’s not their fault.

Which is another way of saying, it’s not their problem.

You could say, I suspect, that the money the Sacklers gave to museums for art and expansion and to schools for educational programs was a benefit to society. Similarly, you might say that the two films one of the third-generation Sacklers made about American prisons were a positive contribution.

But Keefe finds nothing redeeming in such actions. The early philanthropies were financed by ethically questionable business practices, and the later ones by the OxyContin profits. He also suggests that those profits helped funds the two films.

Scapegoats?

The upshot is that the reader comes away from Empire of Pain reviling the Sacklers. Such revulsion seems to be more than deserved.

Yet, I finished the book with a question: Is the catharsis the reader feels at the end — a sense of the bad guys having been named, if not held to account by the courts — a good thing?

I take it as a given, after reading the book, that the Sacklers are morally repugnant. But, I wonder, does Empire of Pain make them scapegoats?

It’s false, I think, to come out of the book feeling that the opioid crisis can be laid completely at the door of the Sacklers. As I say, they did many reprehensible things. Yet, they weren’t alone.

Amoral capitalism

Other drug companies followed the Sackler lead in pushing opioids despite the danger of abuse. Government officials in the FDA, the courts, the DEA and elsewhere let the Sacklers and others get away with making false claims and driving up sales at the cost of ever more ruined lives.

One of the most damning aspects of Empire of Pain is how, as very rich people, the Sacklers have been able to hire high-priced, politically connected lawyers and consultants to make problems go away. Or to shrink problems to unimportance.

Yes, the Sacklers used their money and power and connections. But they aren’t a rare case. Keefe is telling a story about a family that went off the moral rails. In doing so, however, they were enabled by public officials and by the American business ethos.

Implicit in Keefe’s story is one that he didn’t follow very deeply but one that, to my mind, is much more important that the family demonology he produced.

It’s the story of amoral capitalism, a story of a national business culture that puts greed and profit above all else, and a story about a political culture in which moral judgements can be set off to the side when ambition takes centerstage.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.7.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.