As a world leader, Empress Dowager Cixi hasn’t had good press, nothing like, say, Queen Elizabeth I or Queen Victoria.

In terms of historical reputation, those women had their gender working against them but somehow found ways to be loved or, at least, respected. That’s probably because they operated within acceptable and understandable European parameters.

Cixi, by contrast, maneuvered in the mysterious world of 19th-century China, a place often seen by European eyes as, at best, weird, and, at worst, wicked, unnatural, sensual and corrupt.

She was born into a medieval nation, just two years before, a world away, Victoria assumed the throne in Great Britain. And started her life in Emperor Xianfeng’s court as one of a great many concubines, so many that they were grouped into eight ranks, with Cixi assigned to the sixth rank.

Cixi rose to Xianfeng’s No. 2 consort (after Empress Zhen) when she gave birth to a male heir, Zaichun. Six years later, in 1861, the Emperor, at the age of 30, died, and Zaichun ascended to the throne as Emperor Tongzhi under an eight-man Board of Regents.

But not for long.

Cixi and Zhen carried out a relatively bloodless coup (only one of the Regents was executed), and, with the acquiescence and help of Zhen, Cixi became the ruler of China.

She held power for 36 of the next 47 years, governing the nation of hundreds of millions of people through or despite two weak Emperors (her son Tongzhi and her nephew Guangxu) and in the face of greedy and often violent intrusions by European powers.

“A reputation for sexual depravity”

European contemporaries were flummoxed by this strong and, to them, strange woman, comparing Cixi to “Jezebel of Samaria, who slaughtered the prophets of the Lord and rioted with the priest of Baal.” Another wrote, “When the ‘Venerable Buddha’ [Cixi] said ‘Off with his head,’ there was no Alice to retort ‘Stuff and nonsense.’ ”

A century later, Diana Preston, the author of a 2001 history of the Boxer Rebellion, described Cixi as:

“A natural conservative with scant knowledge of the Western world…[who] never hesitated to act with ruthless opportunism…[and whose] reputation for political ambition also became inextricably intertwined with a reputation for sexual depravity and cruelty.”

She was, writes Preston, a “reactionary to the core” who had “incarcerated her nephew the emperor for daring to lead a reform movement.”

“Colossal documentary pool”

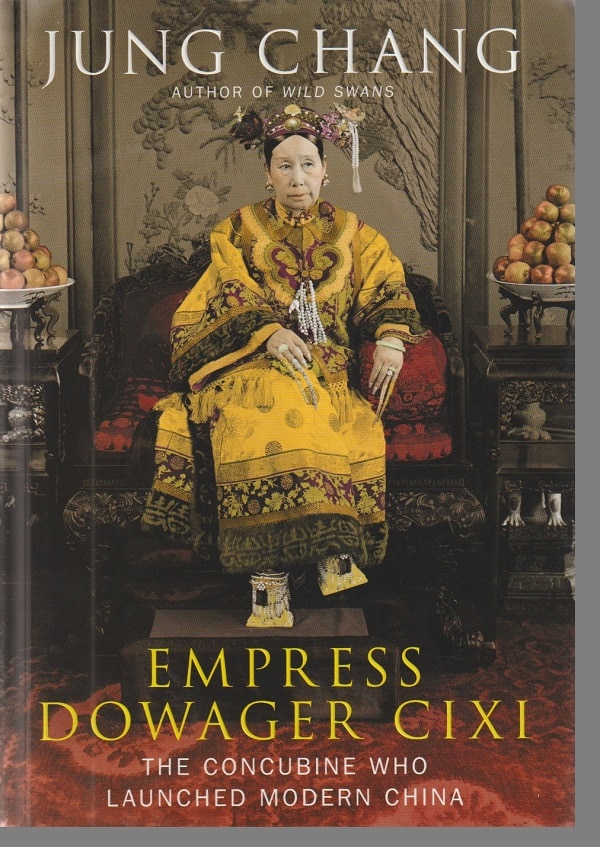

All of which is, according to Jung Chang’s 2013 biography Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China, balderdash.

Well, Chang doesn’t use the word “balderdash,” but that’s essentially what she’s saying.

Chang notes, in the opening pages of her life of Cixi, that she had “the good fortune to be able to utilize a colossal documentary pool” of huge numbers of imperial decrees, court records, official communications, personal correspondence, diaries and eye-witness accounts that only started to come to light after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. The vast majority of documents that she used in preparing this book “have never been seen or used outside the Chinese-speaking world.”

Armed with this arsenal of sources, Chang was able to blow out of the water a century of falsehoods about the Empress Dowager, often describing how a false story was peddled by Chinese opponents to western authorities who were only too happy to think ill of her.

“The plot”

For instance, in 1898, Emperor Guangxu, whom she and her allies had forced into the role of figurehead, worked with a scheming outsider known by the nickname Wild Fox Kang to plan the assassination of Cixi.

For instance, in 1898, Emperor Guangxu, whom she and her allies had forced into the role of figurehead, worked with a scheming outsider known by the nickname Wild Fox Kang to plan the assassination of Cixi.

When Cixi discovered the plans, she rounded up the plotters — but couldn’t nab Wild Fox Kang who escaped and, two years later, raised an army with the help of the Japanese, conquering a number of Chinese cities. She couldn’t permit those arrested to go on trial, Chang writes, because it would have revealed the role of the Emperor, a scandal the imperial system couldn’t face. So, the decree ordering their executions was necessarily vague.

“As Cixi remained silent, Kang’s was the only voice to be heard. When he adamantly denied there was ever a conspiracy to kill Cixi, claiming indeed it was Cixi who had concocted a scheme to kill Emperor Guangxu, his version of events was widely accepted. Sir Claude MacDonald believed that ‘the rumored plot is only an excuse to stop Emperor Guangxu’s radical reforms.’

“So the story of Wild Fox Kang’s attempted coup and murder of Cixi, lay in darkness and obscurity for nearly a century, until the 1980s, when Chinese scholars discovered in Japanese archives…[evidence] which established beyond doubt the existence of the plot…

“Wild Fox Kang entered myth as the hero who lit the beacon of reform and even had a vision to turn China into a parliamentary democracy….While promoting himself, he and his right-hand man, Liang, tirelessly vilified Cixi, inventing many repulsive stories about her in interviews, speeches and writings…

“Almost all the accusations that have since shaped public opinion about Cixi, even today, originated with the Wild Fox.”

Big Lie

The idea that Cixi was the reactionary — see the Preston quote above — was rooted in Wild Fox Kang’s Big Lie.

It is breathtaking, indeed, how successful that Big Lie was for a century and more. Of course, history is replete with such examples — and the present day as well.

As Chang details in this carefully researched and intriguing book, Cixi moved throughout her years of rule to bring reform to China, albeit cautiously and with moderation. Wild Fox Kang and Guangxu and the earlier emperor Tongzhi were the ones who were part of the reactionary movement within the nation.

She made mistakes, most especially her backing of the Boxer movement against Europeans in China and against the European armies that invaded the nation which, Chang writes, “resulted in large-scale atrocities by the Boxers.”

“A legacy manifold and towering”

Nonetheless, by the end of Empress Dowager Cixi, the reader has gotten to know the doughty and clever woman so thoroughly that Chang’s glowing epilogue seems apt and spot-on. She writes:

“Empress Dowager Cixi’s legacy was manifold and towering. Most importantly, she brought medieval China into the modern age. Under her leadership the country began to acquire virtually all the attributes of a modern state: railways, electricity, telegraph, telephones, Western medicine, a modern-style army and navy, and modern ways of conducting foreign trade and diplomacy…

“Above all, her transformation of China was carried out without her engaging in violence and with relatively little upheaval. Her changes were dramatic and yet gradual, seismic and yet astonishingly bloodless. A consensus-seeker, always willing to work with people of different views, she led by standing on the right side of history….

“In terms of groundbreaking achievement, political sincerity and personal courage, Empress Dowager Cixi set a standard that had rarely been matched. She brought in modernity to replace decrepitude, poverty, savagery and absolute power, and she introduced hitherto untasted humaneness, open-mindedness and freedom. And she had a conscience.”

Even at the end

As noted earlier, Cixi’s rule wasn’t completely bloodness. Even at the end.

As Cixi was dying, so was her ineffectual and incompetent nephew Emperor Guangxu. But he was holding onto life, even as Cixi knew her life was slipping away. If she died first, Japan could gain control of China through Guangxu and his allies

So Cixi had him murdered with a huge amount of arsenic.

He died on November 14, 1908. Over the next 20 hours, Cixi arranged all the paperwork and announcement for the succession of his heir, her two-year-old grand-nephew Puyi, with the boy’s reformist father as Regent.

And then she died.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.6.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.