The scribbled telegram text, sent by messenger from the top of Mount Everest, was bleak — but also a bit odd.

Snow conditions bad stop advanced base abandoned yesterday stop awaiting improvement All well

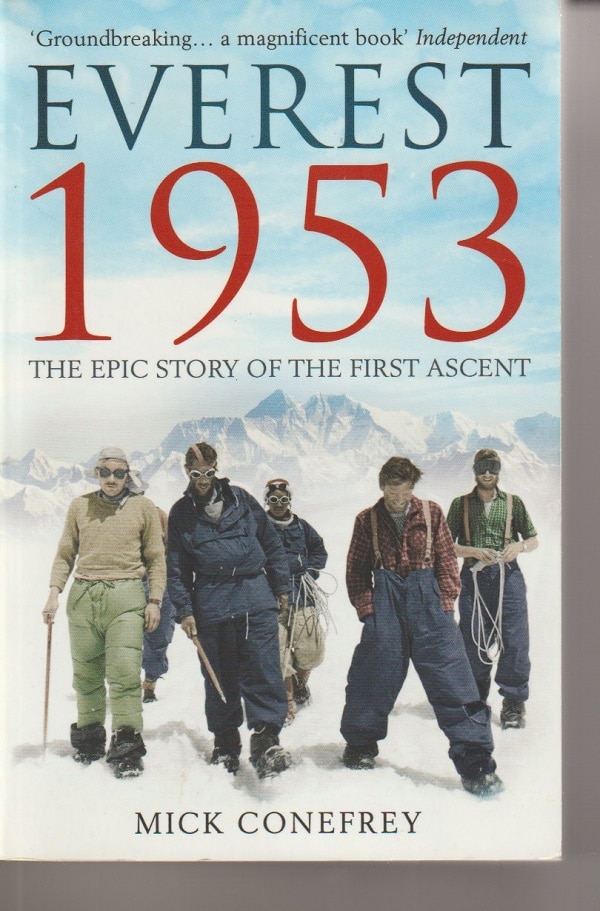

News of failure was not unexpected from the expedition on Everest in late May of 1953. After all, for more than 30 years, mountaineers, particularly those from Great Britain, had been attempting to reach the summit of the tallest peak on earth and had routinely come up short, writes Nick Conefrey in Everest 1953.

This note, carried down the slopes to an Indian radio station and ultimately transmitted in a wire to the British Foreign Office, was sent by James Morris (later Jan Morris), the on-site reporter for the London Times. As he expected, it also went through the hands of ferociously competitive journalists who had bribed functionaries at various points in its journey.

That “All well” at the end was curious, but the rest of the message seemed to confirm the latest rumors about the attempt to climb to the top of the world. So those snoopers ignored the message.

And lost the biggest scoop of their lives.

ALL THIS — AND EVEREST TOO

Of course, they didn’t have the key to the simple code that Morris used, but Charles Summerhayes, the British ambassador to Nepal, did. He knew that “Snow conditions bad” meant that the summit had been scaled. (Failure would have been communicated with the words “Wind still troublesome.”) Other phrases in the text indicated that the successful climbers were Edmund Hillary, a New Zealander, and Tenzing Norgay, a Bothia from Tibet who had lived most of his life in Nepal and India.

The telegram arrived in London on June 1, but most Britons and the rest of the world didn’t learn the news until the morning of June 2 — which just happened to be the coronation day of Queen Elizabeth II. It was as if Great Britain, long battered by economic woes, a bankrupting world war and the unraveling of its empire, had been reborn in sterling silver.

THE CROWNING GLORY, EVEREST CLIMBED shouted on newspaper. Said another, ALL THIS — AND EVEREST TOO. Many writers described the summit as a coronation gift to the new queen and to the nation.

A crackerjack job

As Conefrey makes clear, the conquest of Everest by Hilary and Tenzing was more than an adventure story. It was also an event with international political repercussions. And it was a new chapter in the mushrooming cult of celebrity and the frenzied media that fed it.

Tenzing and Hilary and, to a lesser extent, the rest of their team became world heroes. Nationalists and politicians tried to use the triumph for their own benefit, stirring up a controversy over which of the two men first stepped foot on the summit.

(As the expedition leader John Hunt explained over and over, it didn’t matter since no one could have gotten anywhere without the efforts of the large team. For the record, both men agreed that Hilary got there first.)

Six decades later, though, it’s the adventure story that we’re interested in, and Conefrey does a crackerjack job of telling who was involved and what they faced and how, through grit and will and skill, they overcame one of the most desolate spots on the face of the planet.

Everest 1953 is Conefrey’s second re-telling of the story. His first was an hour-long BBC documentary that he made in 2002 with Amanda Faber, The Race for Everest, available online at the website Vimeo.

The brand “Sherpa”

With Everest 1953, he has much more room to get into the nuances and details of the expedition.

For instance, Tenzing is usually characterized as a Sherpa. In fact, he was a member of the Bhotias, a group of migrants from Tibet that, in Nepal, had a lower status than the Sherpas.

They were regarded as loose cannons, proud and easy to offend, quicker with their knives than their mouths.

The British and the rest of the world either didn’t know or didn’t pay attention to the distinction. And those seeking work on the mountains in Nepal and Tibet didn’t force the issue.

Although the term “Sherpa” properly describes an ethnic group, today it has come to be synonymous with “high-altitude porter.” Like Hoovers and Biros, Sherpas have turned themselves into such a powerful brand that other Nepalis claim to be Sherpas, regardless of their ethnic background.

“The brotherhood of the rope”

It was unusual, but not unheard of, for Tenzing to be accepted as one of the climbers on the 1953 British expedition. His selection to serve on one of the summit teams was a testament to his skill and drive.

The traditional British attitude to the Sherpas was a complicated mixture of paternalism, genuine respect, a vestigial conviction of racial superiority and simple affection. Sherpas were paid employees, who were both porters and manservants — climbers usually had a personal Sherpa for the march in to the mountain, to look after their kit and to the cooking.

As Conefrey notes, Hilary and Tenzing didn’t have a close personal relationship, but respected and trusted each other as climbing partners. It was as a team, deeply connected by “the brotherhood of the rope,” that they triumphed at Everest.

Conefrey writes with liveliness and insight about the everyday details of such an extraordinary effort. At 24,000 feet, for instance, climber Wilfred Noyce and a group of Sherpas spent a night, huddled together in tents.

Wilfred found a flask of lemonade but cursed his luck when the Sherpas noticed it as well and he had to pass it around. When he found a tin of sardines at the bottom of a tent pocket, he ate the lot, convincing himself that there was too little to share. High altitude was not good for moral probity.

“A mother hen”

Sixty years ago, many of the details of the story Conefrey tells would have been unknown or kept quiet. That’s what makes Everest 1953 such a strong and important book. His is a saga of soaring ambition and nitty-gritty human details, of cultural friction and cooperation, of an effort that could be petty or heroic — or, at times, both.

Conefrey writes that Tenzing was different from other Sherpas in his very Western ambition to reach the top of Everest. And he quotes from Tenzing’s ghost-written autobiography:

At that great moment for which I had waited all my life, my mountain did not seem to be a lifeless thing of snow and ice but warm and friendly and living. She was a mother hen and the other mountains were chicks under her wings.

What an image, so poetic.

It is balanced by another startling image, but much more prosaic. Conefrey writes:

Hilary’s final action on the summit…was so shocking that he didn’t mention it until his third and final autobiography, View from the Summit, written some fifty years after the event. He unzipped his fly and urinated.

When you gotta go, you gotta go.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.8.13

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.