The enchanting image of a dancing woman on the cover of Gloria Fossi’s thickly illustrated 1989 Filippo Lippi is more ambiguous than it appears.

Ribbons and linen skirts are tossed here and there by the movements of the tall, thin, blonde woman with red shoes and an energetic right leg executing a complicated kick. For me, the cover recalled the photograph I have of a little dance step by my then-three-year-old granddaughter Emma.

The cover dancer and Emma each express an inwardness, an in-focusing of mind and heart on the sensation of the movement.

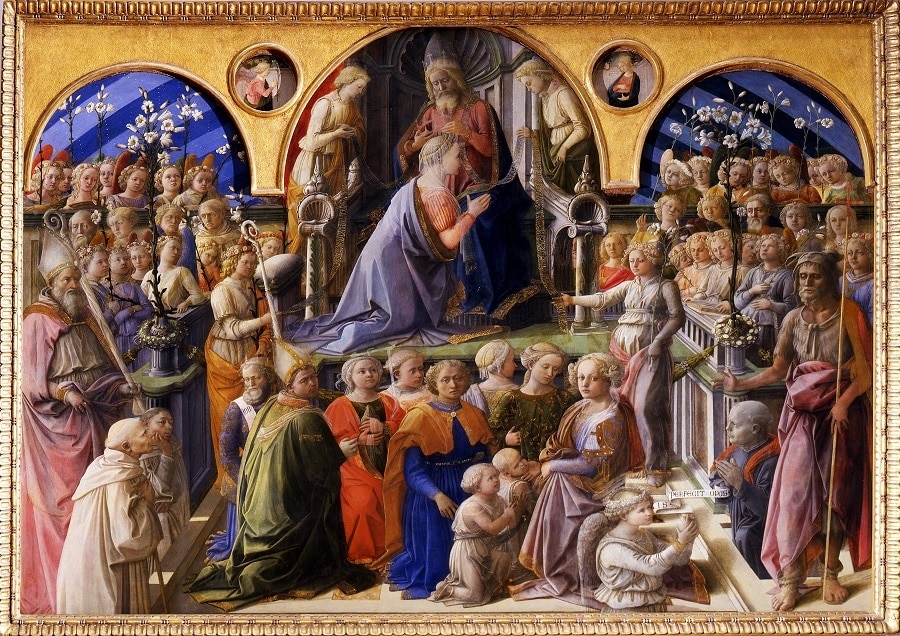

Yet, as the full painting shows, the cover dancer, unlike Emma, is no innocent. The image is a detail from Lippi’s fresco cycle: Stories from the Life of John the Baptist: Herod’s Banquet. The dancer is Salome.

Elegant and brutal

The scene as Lippi painted it contains two moments in the story. On the left is Salome in her dance — distinctive in her flowing white dress, almost virginal, and such a contrast to the more sensual, less clothed version of other artists. In the center is Herod Antipas with Salome’s mother Herodias, his consort. Both had divorced earlier spouses to marry, drawing the criticism of John the Baptist.

Salome so pleased her stepfather with her dancing that he told her he would give her whatever she asked. The right side of the painting shows what happen next.

Salome, still looking girlish and somewhat distanced from her self, is kneeling before her mother and holding a tray with the severed head of the Baptist — the gift that Herodias told Salome to ask of Herod. It is elegant and brutal at the same time.

Of the painting, Fossi writes:

The celebrated dancing Salome…is clearly based on a classical model. Her wild movement is stressed by her hair, blowing in the wind, and her flying garments, typical features of ancient portrayals of Maenads, Victories or Horae.

The ambiguity of her creator

The ambiguity of the dancing Salome echoes the ambiguity of her creator.

Lippi was a monk who “was an eccentric artist whose eccentric behavior was disreputable and dishonored the monk’s habit that he had worn ever since he was little more than a child.” Indeed, he was seen as the polar opposite of the other great painter-monk of the era, Fra Angelico, known as “the devout one.”

He was, writes Fossi, “difficult to deal with…for he had an impatient and excitable temperament, unwilling to abide by rules or honor agreements.” As a result, Lippi was in constant trouble for delivering paintings late and was threatened several times with excommunication. He was notorious for his love of Lucrezia Buti, a young nun. Fossi writes:

It seems Filippo “kidnapped” the girl and took her away from the convent of Santa Margherita in Prato, where she lived with her sister Spinetta.

The couple had two children, a boy and a girl. Lucrezia and her sister later returned to the convent and sisterhood.

“Not dray horses”

Nonetheless, Fossi notes that Cosimo de Medici the Elder, the first great art patron of the Medici dynasty, didn’t hold Lippi‘s scandals against him, saying:

“Great minds are heavenly forms and not dray horses.”

Lippi often painted his lover as the gentle and sweet Virgin for his patrons. And Fossi writes:

Today, most critics agree that the vast pictorial production of this monk, however scandalous his lifestyle may have been, communicates an overriding spirituality, at times, quite introverted, which nonetheless manages to transform the sacred atmosphere of the scenes into one that is totally human and poetic, with great originality and deep psychological insight.

One modern critic asserts that Lippi‘s work expresses “a renewed faith in man’s earthly life.”

Unquestionably, there is in Lippi‘s work — on display in Fossi‘s book, and on view at the Uffizi in Florence and other great institutions — a deeply resounding union of the grit of life and the yearning of faith.

Like Lippi’s work itself, his epitaph, written by the poet, and Agnolo Poliziano, is evocative:

Here in this place do I, Filippo, rest,

Enshrined in token of my art’s renown.

All know the wondrous beauty of my skill.

My touch gave life to lifeless paint…

Giving life to lifeless paint is what painters reach to do. When it works, as it did for Lippi, it gives a glimpse through the paint at the life each of us leads.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.22.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.