Performance artist Jefferson Pinder offers, as a fleeting monument to the long-gone Wall of Respect, a piece called “Bronzeville Etude” that anyone can do — taking a run up and down the streets (map included) around the site at 43rd Street and Langley Avenue where the mural was created in 1967.

He includes photos of him in a suit, tie and white shirt making the run, and, of course, anyone looking at these photos in 2021 knows the danger that a black man can face for simply running, even in broad daylight.

Another fleeting monument comes from artist Kelly Lloyd, a series of tear-off fliers with quotes from figures who were portrayed among the dozens of heroes on the Wall of Respect during its four years in existence.

You’ve seen fliers like this on bulletin boards in laundromats and coffee shops, usually with an announcement of something to sell or rent and, at the bottom of the page, a series of scissored strips, each a phone number, like a kind of fringe. You rip off one of the strips and, then or later, call the number.

Lloyd’s fliers are similar. Instead of the announcement, though, there is the quote, such as from Nina Simone, a Wall of Respect heroine: “There’s no excuse for the young people not knowing who the heroes and heroines are or were.” And the tear-off strips say: “know the heroes & heroines.” The idea is to take what Simone said and, using this strip as a prompt, work the insight into your life.

Pinder and Lloyd are among more than 30 individual and collective artists, writers, theoreticians and activists who accepted editor Romi Crawford’s request to think up what she calls a “fleeting monument” to the Wall of Respect, now collected in Fleeting Monuments for the Wall of Respect.

“No sign”

It would be difficult to think of a single work of art over the past half century that has been more significant for the African American community and, in fact, for all Americans.

Unveiled on Aug. 27, 1967, the Wall of Respect was a mural painted on the side of a dilapidated tavern on the southeast corner of 43rd and Langley Avenue in Chicago’s impoverished Grand Boulevard neighborhood — a revolutionary act of art and politics that has reverberated throughout the nation ever since. It sparked the community-based outdoor mural movement that has provided thousands of neighborhoods of virtually every ethnicity and economic level with a language and format for asserting their pride and distinctiveness.

The 20-foot-by-60-foot mural extended south from a Prima beer sign and covered the two-story building with the images of more than 50 African American heroes, ranging from Malcolm X to Bill Russell, and from W.E. B. Dubois to Dick Gregory, from Charlie Parker to Ray Charles. It was an unprecedented assertion of black identity and an important yet often over-looked moment in U.S. cultural history.

It was a work of art and a community institution and a gathering place that made Mayor Richard J. Daley and other members of the white establishment uneasy. So, it was no surprise when, after a suspicious fire in the building in early 1971, the structure and its mural were razed.

“If one goes to 43rd and Langley in Chicago today,” writes Crawford, “there is no sign that it was ever there.”

Needs to be recognized in a new way

I’ve been there, and, in a city where there are historic markers strewn like seeds across its neighborhoods and many of its blocks as well as brown street signs honoring usually obscure historical personages, there’s no physical commemoration of the wall.

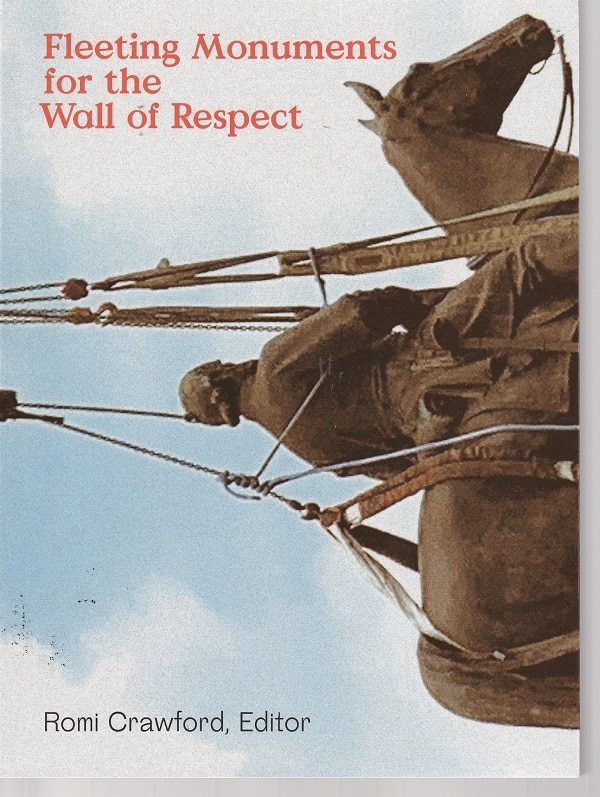

But Crawford isn’t looking for something like that — something like the big bronze statues that are also sprinkled across the American landscape. Many of those statues, particularly in the South, honor heroes of questionable or disreputable heroics, such as Confederate leaders who were traitors to the nation during the Civil War, fighting to protect slavery. Indeed, the photo on the cover of Fleeting Monuments is a sideways image of what appears to be a statue of one of those rebels being hoisted off of its pedestal for removal from the public eye.

“Given its art-historical and social significance, the Wall of Respect needs to be recognized in some way,” Crawford notes. “With this book, I argue against making a monument of or at the site, and for paying tribute to it in ways signaled by its very existence.”

Invitations

The 21 painters and photographers had no permission to paint and create the mural from whoever the building owner was. “It was a guerilla mural,” said artist Jeff Donaldson in a 2003 interview shortly before his death. They knew that their work was likely to be ephemeral. Some of them, at least, saw it as an evolving piece — a kind of a newspaper, according to William Walker — and several sections were repainted at various times with different images and messages.

Not only was the Wall a work of art, but it became the place where poets read and where dancers danced and where musicians made music, an important community space.

Crawford’s argument is that a single large physical thing placed at the site would be everything that the original Wall wasn’t. Instead, the Wall deserves “a commemoration that is comparably complex, dynamic, unruly, and tentative.” Instead of the usual iconic thing, the writers and artists who contributed to Fleeting Moments produce “a polyvocal effect that signals (1) an ever-expanding corpus and (2) myriad personal ways into its history,” she writes.

A large bronze statue is a clear-cut statement of the meaning of the event or person that it remembers. By contrast, the fleeting monuments in Crawford’s book are invitations. “They invite everyone to reconsider the tradition of monument-making while also providing alternative strategies for exercising public memory of an historical topic.”

“who loves Black people?”

Fleeting Monuments is certainly polyvocal, featuring poems and essays, photographs and even a do-it-yourself workshop outline, Ways We Make, to celebrate Black and Brown motherhood, created by Wisdom Baty, a mother, art educator and activist.

“Ways We Make: Nurturing and Building Creative Communities as Mothers of Color is a series of popup workshops that celebrates black and brown motherhood, artistic practices, creative skill-building, networking, and collaboration,” Baty writes. She also notes, “Holding intentional spaces for mothers of color and their children to dialogue about personal growth under the framework of creative lifestyle choices echoes the vitality of Fleeting Monuments.”

The opening section of Crawford’s book includes contributions from people who helped create the Wall of Respect or performed there, such as Abdul Alkalimat, Val Gray Ward and Haki Madhubuti.

Madhubuti, known in 1967 as Don L. Lee, read a poem at the dedication of the Wall of Respect, as did his mentor Gwendolyn Brooks. For Fleeting Monuments, he offers a prose poem that opens with the question: “What does it mean to be consciously Black?” This, he insists, is a necessary way for African Americans to live, given their history as an oppressed people:

“My people and I have gone through the gates of other people’s definitions, imaginations, incarcerations, provocations, rejections, enslavement, and radically debilitating European American acculturation. This seasoning into negro, nigga, coon, colored people, Black, YellowBlack, Afro-Americans, Africans in America, and beyond, all still occupying our daily nightly and sleeping consciousness.”

Several times, Madhubuti asks, “who loves Black people?” and finally answers the question:

“who loves Black people?

“enter the artist and their art,

“enter Black art defining, clarifying, making welcome self-imagination,

“enter African centered culture void of outside interpretation,

“enter art as brain protector…”

Unruly

Particularly pertinent to a celebration of the Wall of Respect is the wordless presentation of Miguel Aguilar, founder of the Graffiti Institute — eight photographs of him tagging or having tagged walls and a sidewalk and even a Sun-Times newspaper box.

Aguilar’s work, writes Crawford, parallels the Wall of Respect inasmuch as it is created “without formal approval of the city but sanctioned by its local constituents” and also is “beyond the bounds of museums and galleries and [produced] with economical materials.

Like the Wall of Respect, gone now fifty years, those who celebrate the mural in Fleeting Moments approach art and community with an openness and an inclusiveness like those who applied paint and posted photographs on the wall in 1967.

They are complex and dynamic and, yes, unruly.

Above all else, though, they celebrate Blackness and its beauty.

Patrick T. Reardon

9.7.21

This review initially appeared in Third Coast Review on 8.1.21.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.