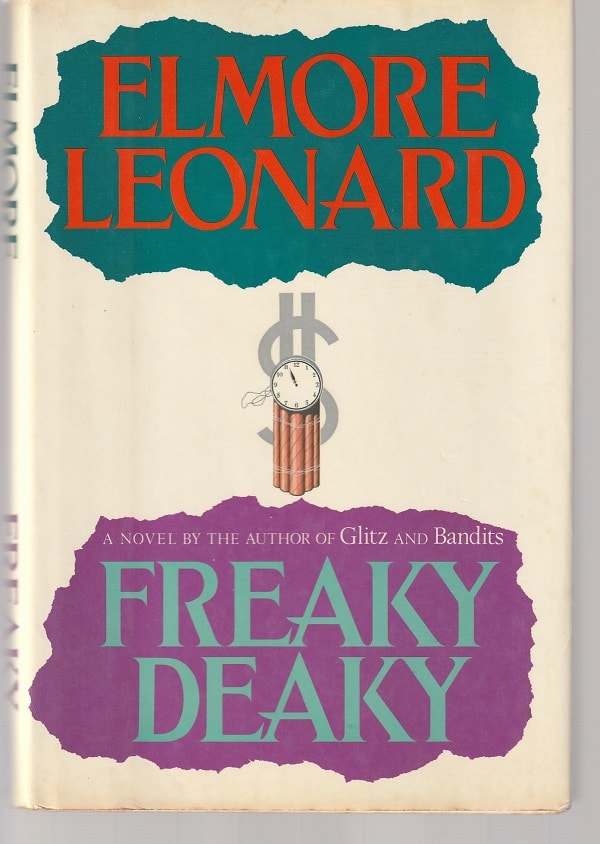

I have a theory about Elmore Leonard’s 1988 novel Freaky Deaky.

I suspect that one of the main characters, Donnell Lewis — an ex-Black Panther and ex-con who is sort of working a scam as the chauffeur and do-it-all for a rich clueless guy named Woodrow “Woody” Ricks, a guy who spends his days constantly and totally doped up on booze and drugs — was supposed to get blown up by one of the many bombs that are floating around the novel and, yes, exploding.

Freaky Deaky is about two former 1960s student radicals who were in it more for the rush than for any principles and who are now trying to make a big score from Woody and his younger brother Mark, both of whom are acquaintances from their college time at Michigan.

Their method, then and now, involves explosives, and that ends up pulling into the story Chris Mankowski, a former police bomb squad investigator who, it turns out, was also at Michigan and knew of, but didn’t know, the radicals, Robin Abbott and Skip Gibbs.

A missing bomb?

By the late 1980s, Leonard was writing novels that had almost nothing to do with solving a crime — although that was an element — but focused on the interactions of quirky people on both sides of the law.

That’s what goes on here, and it’s a lot of fun.

Various characters, major and minor, get blown to high heaven by bombs that Skip builds and hides in unexpected places. And, unless I’m wrong, by the end of Freaky Deaky, there’s one bomb of his that hasn’t been found and hasn’t yet exploded.

“A wet brain”

This is the bomb that, according to my theory, Leonard had planned at the start of writing the novel for Donnell. My theory is that, as he wrote along, the author came to like his character so much that he decided to spare him — and either forgot about the hidden bomb or figured that no one would notice.

Donnell, like most of Leonard’s characters, is a complex guy, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Leonard thought he might be able to use him again in a later book. He did that often enough although, as far as I can tell, he didn’t in Donnell’s case.

This novel opens with a drug lord named Booker — “a bad fucking dude” — who, for a short time, is sitting on a chair to which a bomb is attached. And then he isn’t.

By contrast, Donnell has some redeeming social value. Yes, he has a criminal past, and, yes, his work for the man he calls Mr. Woody can be seen as exploitation of an incompetent. Donnell gets a comfortable life at Mr. Woody’s mansion by keeping him supplied with what he needs, mainly booze and drugs.

Yet, Leonard makes it clear that Mr. Woody is the ultimate lost soul. “Man has a wet brain,” one cop says of him.

“Bottle of ketchup”

Case in point — Donnell and Mr. Woody are talking in the morning when Mr. Woody is heavily hungover:

“You know what I used to think?”

“No, sir.”

“That red things were best for hangovers, in the morning. A really bad one, I’d drink a bottle of ketchup.”

Man was cuckoo.

Later, another character named Greta is sitting with Mr. Woody. As she’s telling him to take better care of himself, she’s looking at his face:

He seemed to be listening now, but it was hard to tell. His face was like a road map, all the red and blue lines in it. If that liver spot on his cheek was Little Rock, there was U.S. 40 going over to West Memphis. The Mississippi came down his now full of tributaries and drainage canals, curved around O.K. Bend at his mouth and went on down to the Louisiana line.

Tender loving care?

Mr. Woody is a mess and has always been a mess, and here’s the thing: Donnell is trying to figure out a way to get a large amount of cash from him, to take advantage of him.

But the bottom line is that Donnell Lewis is the only friend Mr. Woody has, and all the work he does for him — even though the goal is to steal his money — is a kind of care-taking of Mr. Woody.

Tender, loving care? Maybe that’s taking it too far, but it’s still care of some kind.

I think Leonard realized this, and he liked his character and liked that he could have criminal intent and yet still be a kind of friend to Mr. Woody.

That, to my mind, is why the last, unfound bomb didn’t explode.

Of course, there’s also the possibility that I didn’t read closely enough and Leonard told what happened to the bomb and I missed it.

Even so, I like thinking that Leonard liked Donnell and gave him a reprieve.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.26.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.