For a few days, I took an unexpected, disconcerting and enthrallingly odd voyage through an unusual life and a mythic Chicago.

It began when I was reading a book about the history of soul music in Chicago, and the author mentioned a 1978 movie called Stony Island about a fictional band on the South Side who practiced in a funeral home on Stony Island Avenue

During my 32 years as a reporter at the Chicago Tribune, I found this extremely wide street interesting for any number of reasons. For one thing, it was the site of Mosque Maryam, also known as Muhammad Mosque #2 or Temple #2, the headquarters of the Nation of Islam, at 7351 S. Stony Island Ave. Sixteen years ago, I stood across the street from the Mosque as writer Harry Mark Petrakis told me how he used to go to that building when it was the Saints Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church.

From the first time I saw Stony Island, in the early 1980s, it was clear that, at some point in the past, it had been a busy, vibrant street. But, by this time, many of the buildings on both sides had been razed, and the area, part of the South Shore neighborhood, had the look of a crumbling urban ruin. It was as if some section of the ancient, abandoned city of Babylon had been airlifted through time and space to this area just south of the Hyde Park and Woodlawn communities.

The ruin on Stony Island Avenue reflected the ruin that had happened in the blocks around it when, starting in the 1960s, Black people moved in and White residents moved away, bringing about a disinvestment in the neighborhood by White-controlled banks, insurance companies and other institutions, including city government.

The neighborhood was virtually all Black by the time I started covering stories there, an extension of the Black Belt, the historically circumscribed area where, through legal and illegal ways, violent and hidden means, White Chicago kept the city’s African Americans hemmed into a kind of reservation or, as it was called, ghetto — and away from White neighborhoods.

James Purdy’s novel

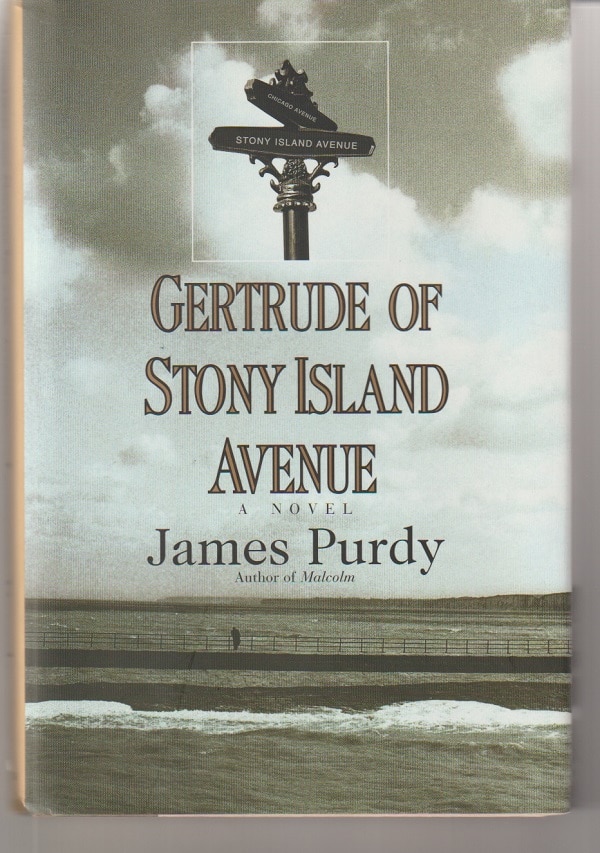

When I read about the movie, I looked it up in the online Chicago Public Library catalogue to get a copy to watch, and, while doing that, I came across a novel that I’d never heard of: Gertrude of Stony Island Avenue by James Purdy.

Purdy, I learned, was a highly respected novelist and playwright who died in 2009 at the age of 93 and who’d been praised in his lifetime by such literary luminaries as Edward Albee, Lillian Hellman, Jonathan Franzen, Dorothy Parker and Marianne Moore. He was in his early 80s when, in 1997, he published Gertrude of Stony Island Avenue, his last novel.

I ordered a copy of the novel, too, based only on its title and Purdy’s reputation. As I usually do, I didn’t search out a description of the story, not wanting to develop any preconceptions about the book.

When I read it, I found myself on a quest that I never could have imagined through a city that I knew frontwards and back, or so I thought.

“Everything you can remember”

It turned out that I did have preconceptions about the book when I started to read it.

I thought that, like the Stony Island movie, Gertrude of Stony Island would be about the neighborhood around the street as I knew it, that it would be about an African American woman and about Black people.

Nope. Instead, as I slowly began to recognize, Purdy’s novel is set in the 1930s, and its characters, for the most part, are affluent white people who lived in the area then. And it’s very much not like the usual Chicago novel.

The central figure is Carrie Kinsella, the wife of Victor, her husband of 40-some years, a man who, now retired, made enough in a real estate career to call a limousine for her whenever she wants to ride somewhere. He is also a man she calls Daddy.

The focus now of Carrie’s life is to understand her daughter Gertrude, a famous, free-loving painter who died two years earlier. Here is how the novel starts:

Daddy is very peevish and irritable. He thinks I may be writing something about Gertrude. I, who seldom had the patience to write a postcard to anyone, and of course more trouble writing a letter. All I do is jot down little notes — recollections of Gertrude.

Carrie is about 60. Daddy, ten years older, seems to be failing in health, and she wonders what she will do when he is gone.

And the chilling thought came to me like someone whispering behind my armchair: You will write down everything you can remember, Carrie, about Gertrude, your daughter, Gertrude of Stony Island Avenue, Chicago.

Visiting her daughter’s “haunts”

With this, Carrie begins a journey that is only slowly revealed to her and to Purdy’s readers — a quest into the unknown that was Gertrude’s life, a pilgrimage that follows in her daughter’s footsteps, an exploration, an adventure, an odyssey in search of Gertrude and herself — and a voyage for a new home, at least, in emotional terms.

The story of that voyage, Gertrude of Stony Island Avenue, is as peculiar, cryptic and absorbing as reading the story of a Chicago political scheme written in runic words on vellum by a Swiss monk.

It is a novel that takes place on the streets of Chicago that echo thickly with the chords of legend and lore.

Carrie is compared to the goddess Demeter who was the consort of her younger brother Zeus and mother of his daughter Persephone. When the young goddess disappeared — abducted by the god Hades with the permission of Zeus — Demeter searched all the earth for Persephone.

Carrie travels around Chicago, visiting her daughter’s “haunts.” It is a search that recalls the numerous Greek heroes who went into the depths of the underworld, the land of Hades, for one purpose or another, including Odysseus who stopped there in his ten-year-long travels to get home.

“His iron nipples”

For Carrie, the search for Gertrude and, as she ultimately realizes, herself is at once gothic in its strangeness while also mundane in its setting in her modern-day Chicago.

For the reader accompanying Carrie, this search is unsettling. (It was for me as I read along.) For instance, Evelyn Mae, an elderly University of Chicago literary scholar is often found amid a Greek chorus of young men.

Gertrude left behind a stained RECORD BOOK, filled with names, addresses and phrases, such as “The broken nails of his sinewy toes/cried out for a sculptor, not a painter” and “His iron nipples gave me a vision that has never left me.”

Daddy, too, has been keeping his own odd manuscript, called AN INDEX OF THE FORGOTTEN ITEMS OF AMERICA, 10,000 and more pages of phrases, dates, names of disappeared celebrities, lines from once popular songs and other curiosities, each page marked, “Compiled by Victor Kinsella.”

Hieroglyphics, Salome and the Red Sea

And it’s not only Greek myths that seem to be operating just below the novel’s surface. For instance, Carrie tells the reader:

Gertrude’s Record Book, despite its incomprehensibility, became a kind of Bible for me. Every page was short, almost unintelligible, yet I read and reread what she had written. I studied her Egyptian hieroglyphics.

When she finds and smokes a cigarette in a room once occupied by someone else’s hated daughter-in-law, Carrie notices that the gold-tipped cigarette has the trademark Salome.

More than once, she makes comparisons to the parting of the Red Sea, such as when she tells Evelyn Mae about Gertrude’s first period and how Gertrude sought solace from her cousin, not her mother.

The story of Gertrude’s first menstruation was too powerful for Evelyn Mae to add one word of comfort or wisdom.

But her closeness made up for it.

My own words were deeper than the Red Sea, deeper than hell.

“Gertrude and I,” I spoke, looking into Evelyn Mae’s eyes, “were never mother and daughter again, little as we had been before. We were never to be together ever, after what had happened.” (Perhaps the Red Sea itself had parted and taken her away to another land.)”

“Ground up and pieced together”

Like many Greek legends, the story of Carrie’s journey into learning about Gertrude and learning about herself is murky and ambiguous. I found myself often understanding the facts of a scene, but knowing also that I had only glimpses of what seemed like many layers of its meaning.

What’s clear is that, by its end, she’s been changed. What’s unclear is what exactly she has found — and who exactly she has become. Only five paragraphs from the novel’s end, Carrie is thinking about Daddy’s chaotic mass of random names and memories, THE FORGOTTEN ITEMS, and she describes it as:

The names, phrases and events, all of America’s past, torn apart, ground up and pieced together in some kind of order, which is disorder but is still all together.

The same could be said of Gertrude’s RECORD BOOK, and, it seems to me, it is probably the best summation of Carrie’s book Gertrude of Stony Island Avenue — a series of obscure and enigmatic experiences “ground up and pieced together in some kind of order.”

Yes, by the final page, Carrie’s life is still disordered, but, in some inscrutable way, it is all together in a way it had never been.

If nothing else, it is a story that she has written herself.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.30.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.