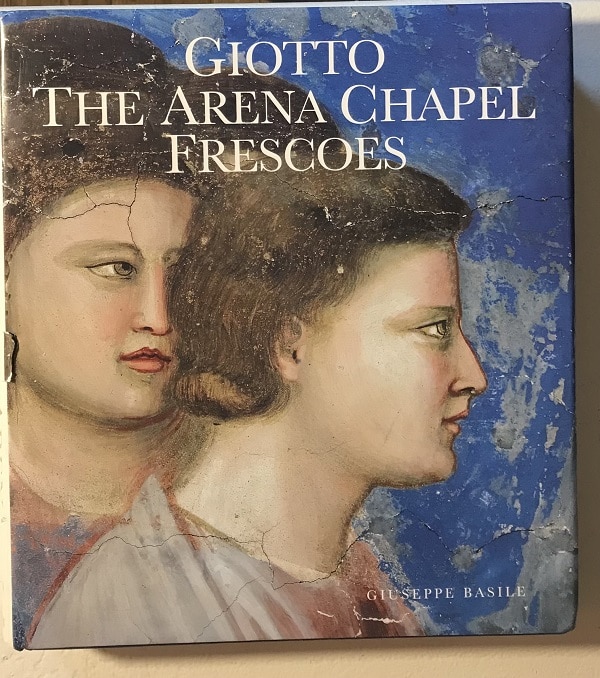

Giotto’s Arena Chapel frescoes, completed during the first decade of the 14th century, are one of the treasures of Western civilization.

And Giuseppe Basile’s Giotto: The Arena Chapel Frescoes, published in 1993, is itself a treasure — a lavish, loving large-format photographic record of the art, featuring hundreds of images, many depicting details with great clarity and at extreme close-up.

The frescoes — reverent, sumptuous, exuberant and alive with action and character — represented a breakthrough in Western art, a sharp turn away from the stiffness and stylized images of earlier work. The small newly built structure in Padua, Italy, was decorated by Giotto and his assistants with 37 panels portraying important events in the life of the Blessed Virgin Mary and of Jesus as well as an imposing Last Judgment.

Basile, an Italian who, at the time his book was published, was in charge of the conservation of the Arena Chapel art, divides his book into six main chapters, each relating to a particular group of panels, such as “The story of Joachim and Anna” and “The life of the Virgin.”

An often-breathtaking encounter

Within each chapter, the panels are presented in three stages:

- In the first, each page has two full panels. This means that facing pages show four of the panels and give some approximation of how the individual paintings relate to others in their section.

- The second section shows details of the panels, often filling one or two of the pages.

- Large images that focus much more narrowly on even smaller details of the images comprise the third stage.

With this approach, Basile gives the reader extraordinary access to these works, providing an often-breathtaking encounter with the art and vision of Giotto.

For technical reasons, much of the most lustrous blue in the panels has faded over the centuries. Yet, enough of it remains that the blue continues, after six hundred years, to draw the viewer into the scenes.

Striking impressions

Basile’s book is so munificent that it invites the reader to engage in many viewings of the works and their details. Here, I am only going to point out a handful of striking impressions that the book left with me.

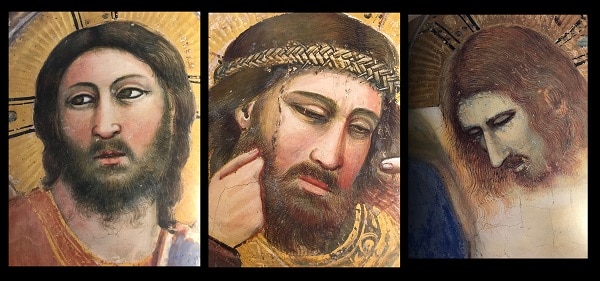

Giotto’s depiction of Jesus, for instance, is amazing for its emotional acuity and visual characterization.

Consider these three portraits of the young Jesus — at his baptism, at the wedding feast in Cana and as a baby.

These three images show Jesus after his arrest, standing before Caiaphas, being whipped and scorned, and dead on the cross.

Here are two images of the resurrected Jesus — outside the tomb, standing before Mary Magdalene, and during the Last Judgment.

This, it is clear, is the same man. It is also clear that he ages and, in his Passion, suffers and, in his resurrection, rises to a new, greater dignity.

One stunning detail

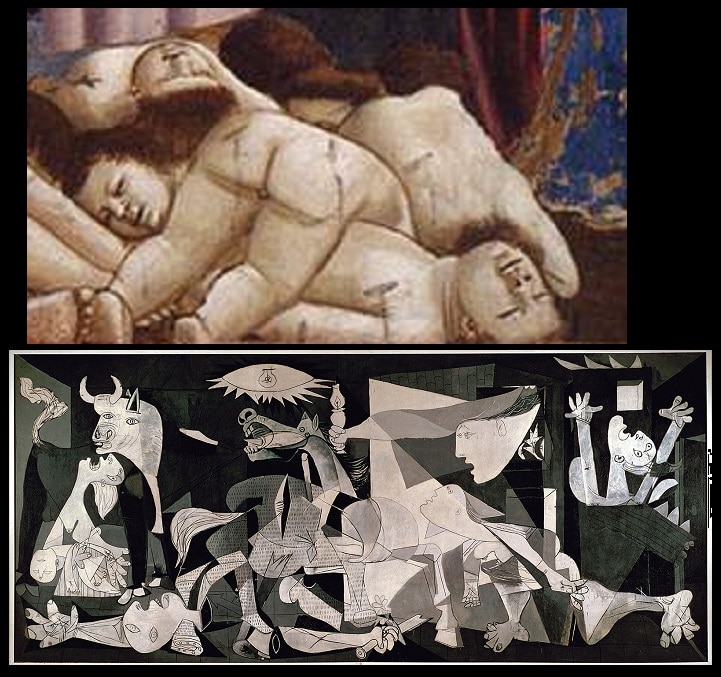

Basile’s extreme details are often striking, but I found one to be stunning — the bodies of the babies killed by Herod in the Massacre of the Innocents.

Indeed, it could easily have been one of the inspirations for Picasso’s Guernica, five centuries later.

Great art and great humanity

Finally, I was also stunned by Giotto’s savviness about infancy and his ability to capture a particular moment of Jesus’s babyhood — his presentation in the Temple.

Two things are going on here, and, by paging back and forth among several images of this panel, the reader can see the full depth of Giotto’s art.

If you look at the eyes of Jesus, you can see his pupils are at the far left. He’s giving a sidelong gaze at Simeon, and that is exactly what a baby does in such a situation, looking at this old guy with a mix of curiosity and uncertainty. He’s not alarmed, not fully, but he could get there quickly enough.

As proof of that, his right arm is reaching out to his mother who, at the same time, is reaching out her two hands, maybe in offering Jesus to Simeon but, more likely, it seems to me, in getting ready to save him from panic.

This scene sums up much that Giotto brought to his work in the Arena Chapel and much that Basile works so hard to make evident — the great art of Giotto and his great humanity.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.19.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Meaningful piece. Thank you.