After nearly 60 years, Gislebertus: Sculptor of Autun by Denis Grivot and George Zarnecki remains the best book on the astonishingly vivid, highly original art of the medieval French master.

The large-scale Grivot-Zarnecki work, published in 1961 by the Orion Press with Trianon Press, is distinguished by Gerard Franceschi’s sumptuous photography.

In those lovingly lighted and recorded images, Franceschi details the eloquent, distinctive and, above all, humane carvings by Gislebertus (and, in some cases, by assistants he oversaw) in the myriad doorways, tympanums and capitals at the Cathedral of Saint Lazare at Autun.

In 1999, art historian Linda Seidel published Legends in Limestone: Lazarus, Gislebertus, and the Cathedral of Autun, a scholarly look at the art of Gislebertus within the context of the religious pilgrims of his era and the art pilgrims of today. Included in her 6-inch-by 9-inch book were nearly 100 images, most of them of the sculptor’s work.

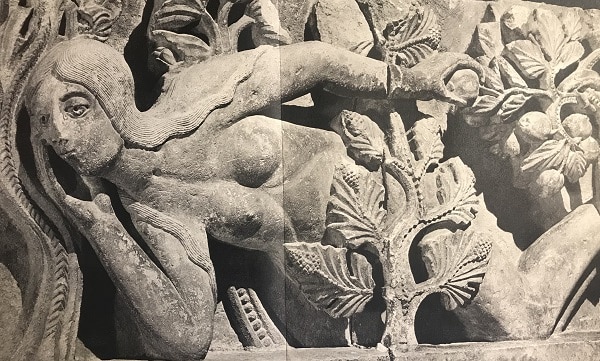

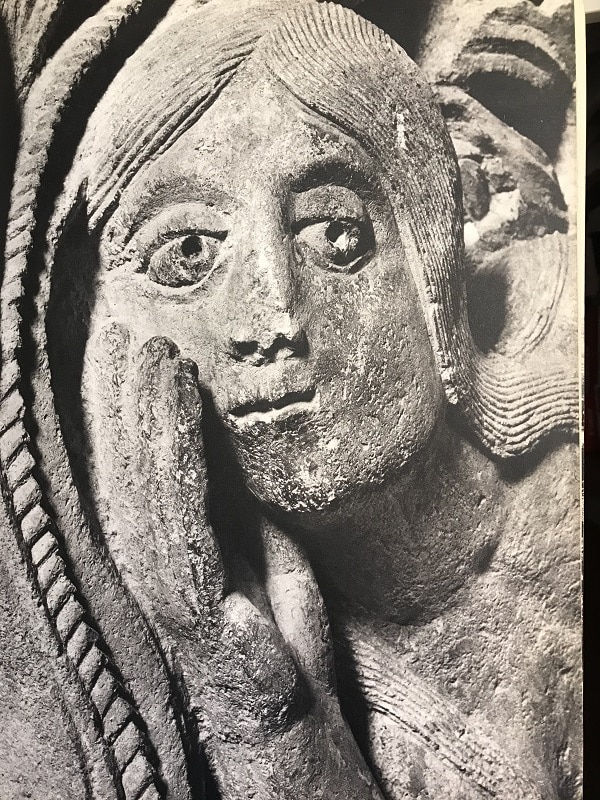

Eve

By contrast, the Grivot-Zarnecki book, with twice as many images, features pages that are 9 inches by 12 inches, providing, in many cases, a double-spread of 18 inches by 12 inches to display the best of the sculptor’s work, the most exquisite of which is his carving of Eve.

In an introduction, T.S. R. Boase, a British art historian and Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University, describes this carving as “one of the most sensuous of all Romanesque sculptures.” He continues:

Nowhere else is the female body treated with such realism or such disturbing beauty; it belongs to another age than the flatly articulated nudes of medieval manuscripts, and the haunting face, whispering through her hand to Adam, has a seductive quality that no other 12th-century artist has equaled.

And few others in the history of art.

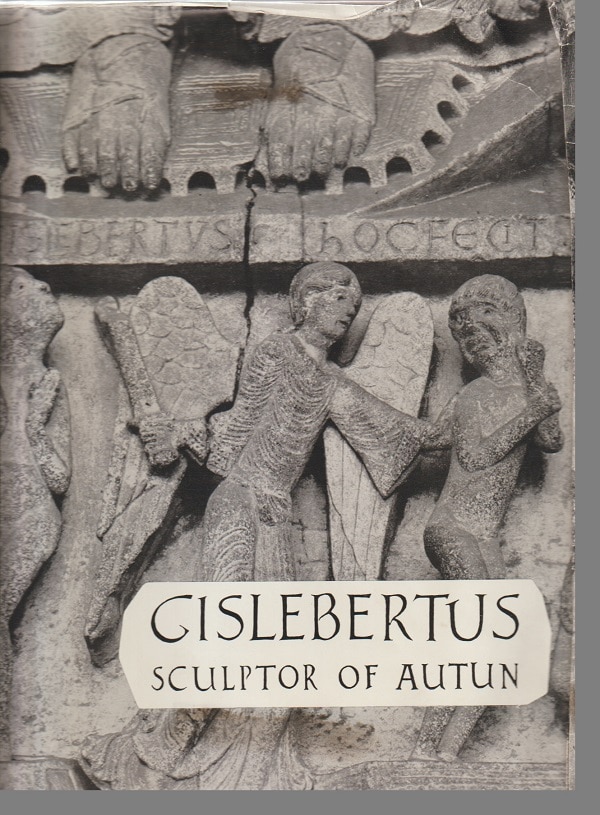

“Hoc fecit”

Gislebertus is a rare medieval artist whose name is known. That’s because he signed his work in a very prominent way on the very prominent west tympanum of the cathedral:

“Gislebertus hoc fecit” or “Gislebertus made this.”

It’s possible, as some modern scholars believe, that that’s actually the name of the patron who paid for the work. Yet, Gislebertus — which can be translated as Gilbert — is the name by which this artist has been called for nine centuries.

Little is known of his life. It is believed that he learned his craft in the ornamentation of the Cluny Abbey and then worked at the Vézelay Abbey. His labors at Autun have been dated from 1120 to 1135. But, beyond such suppositions, he fades away in history.

Not his work.

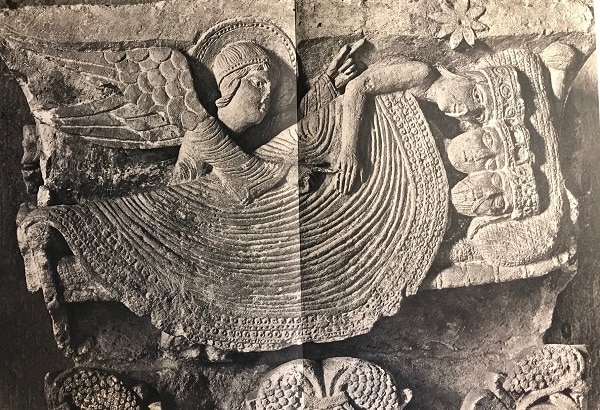

The Magi

For me, Gislebertus’s depictions of the three kings are among the most touching and affecting of his work, after his Eve.

In one, The Dream of the Magi, the three kings, wearing their jeweled crowns, sleep in bed together under a marvelously nuanced bedspread. An angel has arrived to warn them to leave the country without telling King Herod that they have found the Baby Jesus. With a single outstretched finger, the angel touches the little finger of one king, whose eyes have opened while the others sleep.

Grivot and Zarnecki describe this scene as “delightfully naïve,” and they’re right.

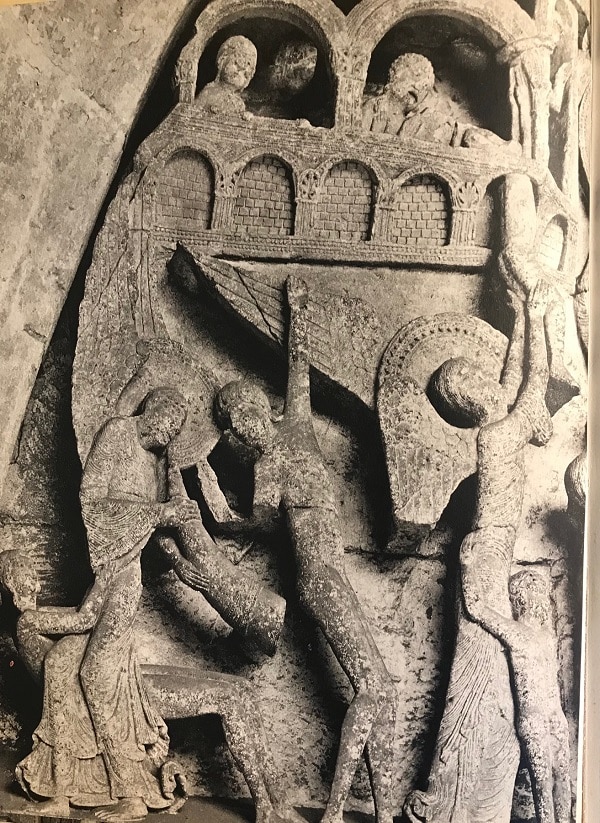

Another is the Adoration of the Magi in which, write the authors, “The Virgin and Child, with St. Joseph, somewhat perplexed behind them, are shown seated under a rich, arcaded structure.” The kings, each in his own way, exhibit great reverence to the newborn child in “an exquisite composition, full of touching tenderness.”

Claws and a happy soul

However, Gislebertus — a medieval Christian, after all — could be downright gruesome when considering the punishments that faced sinners.

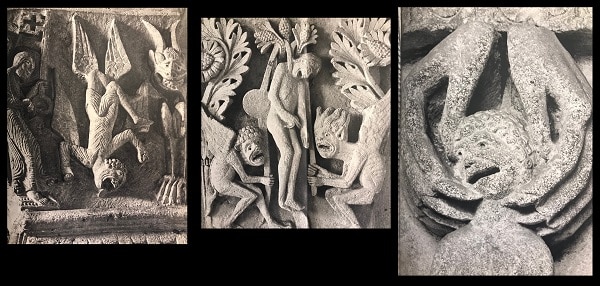

The image on the left is a portrayal of the story of Simon Magus, a sorcerer from the Acts of the Apostles who, according to later stories, came to a bad end when he tried to fly with the help of a devil. The center image is of Judas hanging himself.

On the right is a doomed soul, caught and strangled in giant claws.

Balancing the host of doomed souls on the right of the tympanum of the doorway of the west façade is a similar host of saved souls on their way to heaven.

In the above photo, one angel on the left is blowing the horn of the Day of Judgement while another on the right is literally pushing a happy soul into heaven.

Artful artlessness

The sculptures of Gislebertus are far from realistic. There is a highly artful artlessness to them, an innocence that makes them immediately accessible to the viewer.

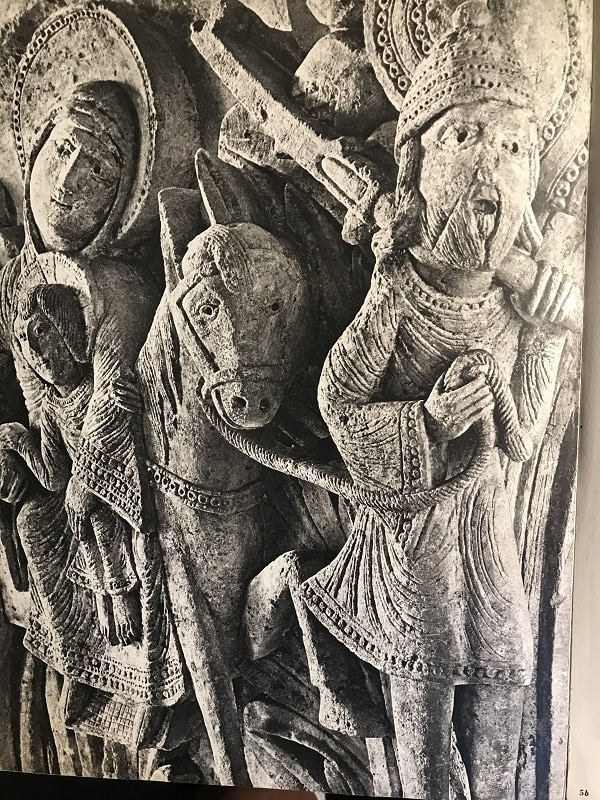

As with this image of The Flight into Egypt, Gislebertus packs his work with a deep emotional resonance.

They were a wonder for the people of 12th-century France to marvel at. And remain so today.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.6.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.