After the 87th Precinct detectives took the killer downstairs to the detention cells, they sat in the squadroom, quiet and thoughtful.

“Why do you suppose he put on the dead man’s clothes?” Kling shuddered. “Jesus, this whole damn case…”

“Maybe he knew,” Carella said.

“Knew what?”

“That he was a victim, too.”

Miscolo came in from the Clerical Office. The men in the squadroom were silent.

“Anybody want some coffee?” he said.

Nobody wanted any coffee.

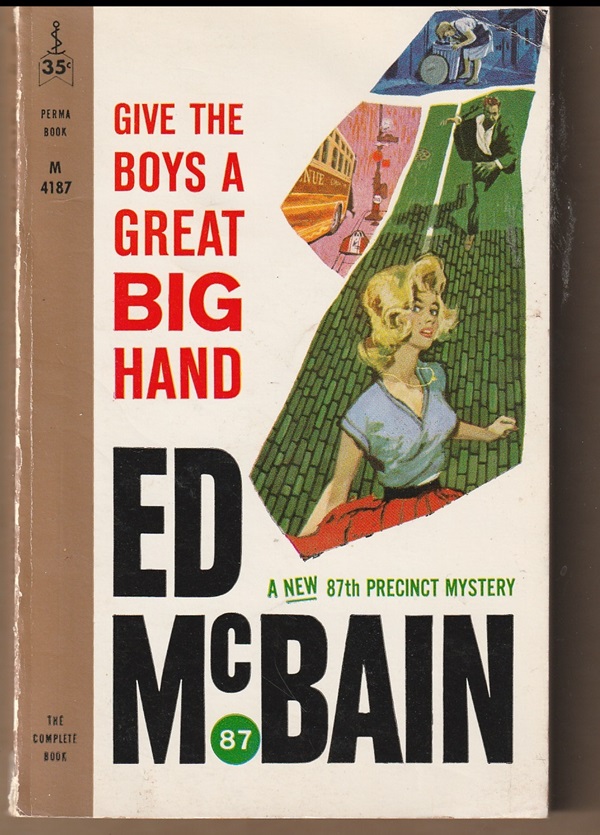

These are the last sentences of Ed McBain’s Give the Boys a Great Big Hand, published in 1960. It was the 11th book in what eventually became a series of 55 novels about these detectives that hit bookstores between 1956 and 2005.

This scene says much about the 87th Precinct investigators — and about the popularity of the series for more than half a century.

The guys in the squadroom

Unlike superheroes with their great powers, unlike such super cool spies as James Bond, the guys in the squadroom are, well, guys.

Most aren’t jaded to the pain, violence and grisliness they witness every day, such as the discovery that starts this novel (a man’s very large hand, severed at the wrist) and gives the book its black-humor title. They are professionals who do their job but always remain human beings who are able to empathize with other human beings, even killers.

The central crime in Give the Boys a Great Big Hand involved a fantasy that the killer believed in deeply, a fantasy that resulted in his committing murder and also resulted in yet another fantasy, one that led him to lose his reason.

When he broke down and gave a detailed confession of his crime, the detectives saw him for what he was, a killer but also a deluded fellow human being.

They got the rest of the story from him in bits and pieces. And the story threaded the boundary line, wove between reality and fantasy.

And the men in the squadroom listened in something close to embarrassment, and some of them found other things to do, downstairs, away from the big man who sat in the hard-backed chair and told them of the woman he’d loved, the woman he still loved.

“Hey, Chico”

Yes, the 87th Precinct detectives are human enough to be empathetic. They’re also human enough to get under each other’s skin, such as when Andy Parker, one of life’s insensitive, thoughtless bullies, returns to the squadroom on a warm later winter day and right away starts to needle his Puerto Rican colleague.

Yes, the 87th Precinct detectives are human enough to be empathetic. They’re also human enough to get under each other’s skin, such as when Andy Parker, one of life’s insensitive, thoughtless bullies, returns to the squadroom on a warm later winter day and right away starts to needle his Puerto Rican colleague.

“This is the kind of weather you got back home, hey, Chico?” Parker said to Hernandez.

Frankie Hernandez, who’d been typing, did not hear Parker. He stopped the machine, looked up and said, “Huh? You talking to me, Andy?”

…“I was born here,” Hernandez said.

“Sure, I know,” Parker said. “Every Puerto Rican you meet in the streets, he was born here. To hear them tell it, none of them ever came from the island. You’d never know there was a place called Puerto Rico, to hear them tell it.”

“Yeah?”

And it goes on like that for a while, and McBain writes:

Hernandez was not angry, and Parker didn’t seem to be angry, and Carella hadn’t even been paying any attention to the conversation.

But Parker continues to badger the other man until, out of the blue, Carella tells him to knock it off.

“When did you become the champion of the people?”

“Right this minute,” Carella said, and he shoved back his chair and stood up to face Parker.

“Yeah?” Parker said.

“Yeah,” Carella answered.

“Well, you can just blow it out your…”

And Carella hit him.

Which was something of a surprise to both men because Steve Carella is a pretty even-tempered guy.

“Good riddance”

And it’s not just the detectives who are human in the 87th Precinct stories. So are the men, women and children who move through the squadroom’s days, such as Martha Livingston, a brassy, brash, loud-mouth picked up when her boyfriend back-talked the cops.

They were at her apartment looking for her son Richard, and, now, at the station, she is telling them again that she doesn’t know where he is.

“Good riddance to bad rubbish. The people he was hanging around with, he’s better off dead. I raised a bum instead of a son.”

“She sat quite still”

Lieutenant Byrnes asks about her husband. She says he’s dead. Did he die or did he leave? “It’s the same thing, isn’t it?…He left.”

As for her son, she says,

“I don’t know what he done, the little bastard, and I don’t care. Gratitude. I raised him alone after his father left. And this is what I get. He runs out on me…I hope he drops dead, wherever he is. I hope the little bastard drops…”

And suddenly she was weeping.

She sat quite still in the chair, a woman of forty-five with ridiculously flaming red hair, a big-breasted woman who sat attired only in a silk slip, a fat woman with the faded eyes of a drunkard, and her shoulders did not move, and her face did not move, and her hands did not move, she sat quite still in the hard-backed wooden chair while the tears ran down her face and her nose got red and her teeth clamped into her lips.

Yes, the 87th Precinct detectives are human. And so are the other characters in this and other Ed McBain novels.

And so is Ed McBain.

Patrick T. Reardon

2.6.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.