It is a telling irony that Lucy Parsons — one of the most famous African-American women in Chicago’s history — pretended she wasn’t black.

Not only that. According to historian Jacqueline Jones, Parsons did little or nothing to help black Chicagoans despite her 70-year career as a labor activist, anarchist and would-be revolutionary in the city.

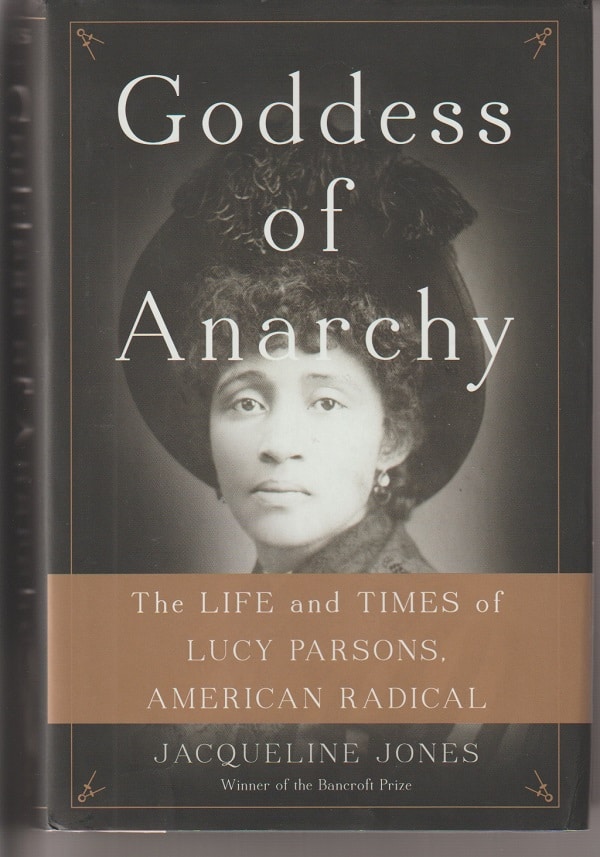

That was true from 1873 when Parsons, then in her early 20s, arrived in Chicago with her husband Albert and began agitating on behalf of workers. As Jones writes in her 2017 book Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical:

Living in a self-sufficient, cloistered, virtually all-immigrant neighborhood, they drew upon European traditions of class struggle that had no room for African Americans. And most white workers, regardless of ethnicity, saw the black man primarily as a potential strikebreaker, a menace to their own livelihood.

Oddly, Albert, a white former Confederate soldier, had built a political career in Texas by urging civil rights for that state’s blacks. His indifference to black Chicagoans, Jones writes, suggests that his pro-black work there had been opportunistic, a means for advancement within the Republican party.

For his wife, there was much more at stake.

A fearsome presence

Perhaps the most striking fact about the life of Lucy Parsons is that, in the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, she was able to establish herself as a popular writer, theorist and speaker within radical circles as well as a fearsome presence to the mainstream powers of order, business and capitalism.

This was a time when American women were expected to leave politics, labor issues and social policy to men. Among radicals of all stripes, women had a bit wider rein.

Nonetheless, no other woman was as eminent in Chicago socialist circles as Lucy Parsons was. And hers was an eminence that grew even greater in her widowhood when, after a highly irregular trial, Albert was one of four socialist leaders hanged for their alleged parts in the bombing at Haymarket Square during a radical meeting. Seven police and at least four other people were killed by the bomb and by the shooting from both sides that followed. Albert Parsons and the others executed for the act were, ever after, seen as socialist martyrs.

Goddess of Anarchy makes clear that Lucy Parsons was a bright, energetic and driven woman, a writer of style and zest (amid the often-turgid theoreticians of the far left) and a speaker of great intensity and vigor.

Through force of will and character, she seized a place — awkward at times — among the leadership of anti-capitalism socialism and anarchy in Chicago and the nation. And she held it.

And all the while, she insisted that she was a mix of Mexican and American Indian.

“Copper-colored complexion”

At times over the decades, interviewers and other observers would accept Parsons at her word. Much more commonly, though, newspaper reporters and white leaders described her as black.

Jones recounts these descriptions often in Goddess of Anarchy, and it seems clear that Parsons’s race was an open secret. At the same time, it seems clear that, for the purpose of advancing the cause (especially after the martyrdom of Albert Parsons), radical activists ignored the question of her race, her protestations of being Mexican and Indian giving them enough of a screen. Jones writes:

From the time she arrived in the city, she would go to great lengths to deny her own African heritage.

Since Parsons was in a city where no one knew her mother, she had partial success in confusing the issue since “many observers could not determine her precise origins from the color of her skin or the texture of her hair,” according to Jones. After all, she was writing and speaking on behalf of white immigrants.

Taking up the cause of long-suffering black domestics would have resulted in calling attention to herself and risking derision or worse. Nevertheless, ignoring workers who shared her African ancestry only brought so much protection.

Throughout her life, those who were opening hostile to her politics would point to her copper-colored complexion and quickly label her a “nigger.”

And not just those hostile to her noticed the shade of her skin. Jones quotes one neighbor who recalled Parsons as “a thorough lady in her manners and…much respected despite her complexion.”

“Exterminate them all”

Neither Albert Parsons nor any of his codefendants threw the Haymarket bomb, and the trial that sent four to their deaths was a travesty of law and justice.

Nonetheless, recent commentators, such as Timothy Messer-Kruse in The Haymarket Conspiracy, have argued that anarchist leaders bore great responsibility for the bomb because of their years of preaching what was known in socialist circles as “propaganda of the deed” — the use of dynamite and guns against the rich and powerful.

Jones doesn’t discuss directly any responsibility that Albert Parsons might have had for the bomb, but she does delineate his efforts in speeches and conversations to promote such actions. For instance, in an interview with a Chicago Tribune reporter in 1878, Parsons said:

“We intend to carry our arms with us, and if the armed assassins and paid murderers employed by the capitalist class undertake to disperse and break up our meetings…they will meet foes worthy of their steel.”

In the mid-1880s, he was proclaiming:

“I say to you, rise one and all and let us exterminate them all; woe to the police or militia who they send against us.”

In 1885, he told another crowd that “it was only a matter of time before the working men would have to assert their rights by dynamite and pistol.”

Jones suggests that Parsons was preaching such violence simply to scare the powers-that-be into granting concessions to workers. Perhaps.

But, in a loud roar, many other radicals in Chicago and around the world were preaching such violence in speeches and in print — including his wife.

“Those little methods of warfare”

In her essay “A Word to Tramps,” published in the radical newspaper The Alarm on October 4, 1884, Lucy Parsons — with much greater skill than most anarchist writers — played on the heart-strings of readers who knew that, on any given day, destitution was only a moment away.

She writes to the father-husband who can no longer support his family and is now thinking of drowning himself in Lake Michigan. Instead, she tells him:

“Stroll you down the avenues of the rich, and look through the magnificent plate windows into their voluptuous homes, and here you will discover the very identical robbers who have despoiled you and yours. Then let your tragedy be enacted here! Awaken them from their wanton sports at your expense. Send forth your petition, and let them read it by the red glare of destruction.”

Lest her readers miss her intent, Parsons tells them “avail yourselves of those little methods of warfare which Science has placed in the hands of the poor man.” And to make her point extremely clear, she ends:

“Learn the use of explosives.”

Toothless threats

After her husband’s execution, Lucy Parsons became a symbol of the struggle for better conditions as well as a promoter of that effort in speeches and writing. She was often feared by government officials in Chicago and in many places where she traveled to speak to radical groups. In retrospect, though, it’s clear that Americans anarchists, such as her, were ultimately toothless threats.

U.S. workers weren’t as downtrodden as those in Europe, weren’t as ready to cast their fate and future with revolution. Despite the strictures that limited economic mobility, many poor American workers felt more optimistic than their counterparts across the ocean about finding a better life for themselves and their children.

Anarchist actions in the U.S. resulted in small, temporary victories on occasion, but usually caused backlash that harmed middle-of-the-road efforts for labor concessions.

As Jones chronicles the twists and turns of Lucy Parsons’s life within the small world of radical America, it’s clear that it really was a small world. She and other radicals had no systematic solution to the problems that workers fought — except blow the whole thing up. In the short run and the long run, this didn’t gain any traction.

Lucy Parsons never had as much impact on the history of the United States as she sought to have. She never sparked a mass movement against capitalism.

She and her anarchist colleagues were outliers. They existed on the edge of the struggle of workers for a better life.

They were a far-left option that was rejected. In their violent rhetoric, they served best, perhaps, as a contrast to the more reasonable labor leaders who sought leverage against the owners but also knew that compromise was necessary to accomplish anything.

Lucy Parsons and her circle wanted nothing to do with compromise. And they accomplished next to nothing.

Patrick T. Reardon

9.10.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

So today we have Jessica Krug who made a career (until she was exposed) of being Black. And then there is Rachel Dolezal who lead a NAACP chapter claiming to be Black but wasn’t.

Great review of a well-written book. I think Jones is more supportive of evolution without violence (as am I) than of attempts at quick, deadly attempts to overthrow a system. I suspect that an author more sympathetic to Parsons’s attraction to violence would present her more favorably.

Yeah, I noticed a number of Amazon.com reviews that didn’t like the book. I figured they were from anarchists and radical socialists.