At the start of the Great Flood:

And a little black spot begun to spread,

Like a bottle of ink spilling over the sky;

And the thunder rolled like a rumbling drum;

And the lightning jumped from pole to pole;

And it rained down rain, rain, rain,

Great God, but didn’t it rain!

At the beginning of the story of the Prodigal Son:

Young man—

Young man—

Your arm’s too short to box with God.

At the end of the Passion of Jesus:

On Calvary, on Calvary,

They crucified my Jesus.

They nailed him to the cruel tree,

And the hammer!

The hammer!

The hammer!

Rang through Jerusalem’s streets.

The hammer!

The hammer!

The hammer!

Rang through Jerusalem’s streets.

“Seven Negro Sermons in Verse”

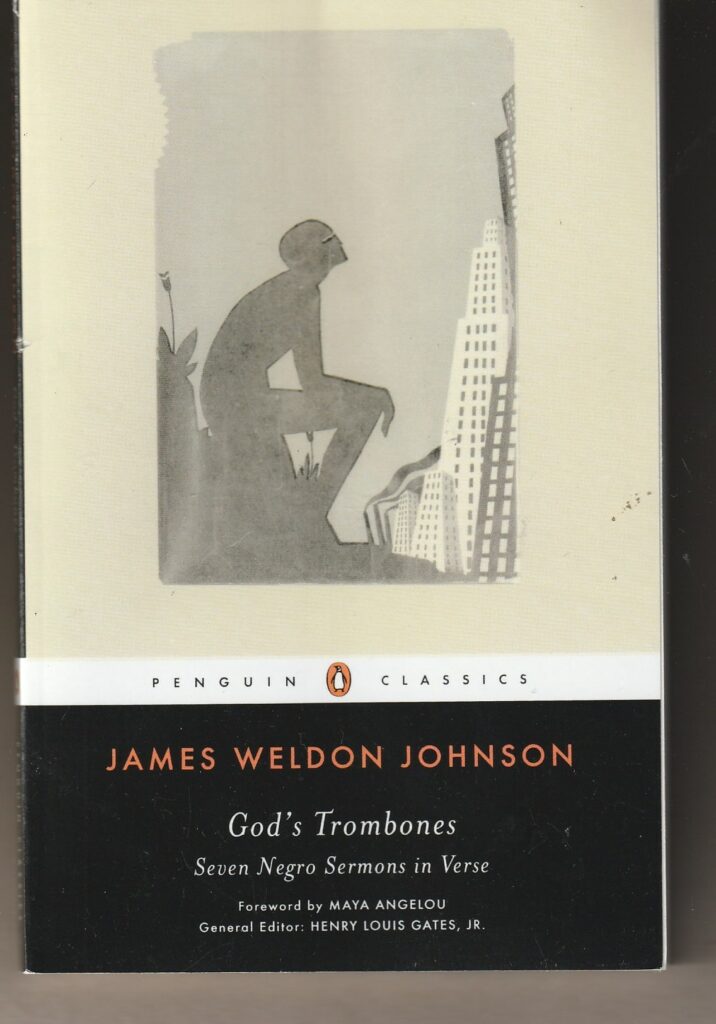

Nearly a century ago, using the Black folk sermon as an inspiration, James Weldon Johnson composed God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. Published in 1927 with start monochromatic drawings by Aaron Douglas and chapter headings distinctively lettered by C. B. Falls, it is a classic of African American literature.

“The hammer! The hammer! The hammer!” — there is a visceralness to these sermon-poems, echoing the emotional edge and rhetorical slice that preachers brought to formula-ed lessons from the pulpit, emotion and rhetoric rooted in the beauty of the King James Version of the Bible and the pain of slavery and racism.

“Too short to box with God” — “thunder rolled like a rumbling drum” — In a preface, Johnson recalled watching a famed visiting preacher who abandoned his prepared text and “started intoning the old folk-sermon that begins with the creation of the world and ends with Judgment Day.”

Johnson reports that an electric current ran through the crowd, and it was a moment “alive and quivering.”

He strode the pulpit up and down in what was actually a very rhythmic dance, and he brought into play the full gamut of his wonderful voice, a voice — what shall I say? — not of an organ or a trumpet, but rather of a trombone, the instrument possessing above all others the power to express the wide and varied range of emotions encompassed by the human voice — and with greater amplitude.

It was at that moment, Johnson writes, that he began jotting down ideas for the first sermon-poem in God’s Trombones “The Creation.”

“The rumble of chariots”

And Pharaoh called the overseers,

And Pharaoh called the drivers,

And he said: Put heavier burdens still

On the backs of the Hebrew Children.

How could the story of Exodus not resonate deeply with enslaved Blacks and, after emancipation, Blacks hemmed in by prejudice and hate? “Let My People Go” is the title of Johnson’s poem.

And, after being sent away by Pharaoh after that worst of plagues, that first-born-killing plague, the Children of Israel were chased by Pharaoh and looked back and

Saw Pharaoh’s army coming.

And the rumble of the chariots was like a thunder storm,

And the whirring of the wheels was like a rushing wind,

And the dust from the horses made a cloud that darked the day,

And the glittering of the spears was like lightnings in the night.

.

And the Children of Israel all lost faith,

The children of Israel all lost hope;

The “Deep Red Sea” was blocking their escape. They were caught. But then “God with a blast of his nostrils/Blew the waters apart.” And they crossed dry land.

And, then, God “unlashed the waters” onto Pharaoh and his army.

“Till he shakes old hell’s foundations”

In that great day,

People, in that great day,

God’s a-going to sit in the middle of the air

To judge the quick and the dead.

That great day is “The Judgment Day,” the final poem in God’s Trombones. And it will be the day that God tells Gabriel to blow his horn.

Then putting one foot on the mountain top,

And the other in the middle of the sea,

Gabriel’s going to stand and blow his horn,

To wake the living nations.

And, again, he will blow his horn, “like seven peals of thunder.”

Then the tall, bright angel, Gabriel,

Will put one foot on the battlements of heaven

And the other on the steps of hell,

And blow the silver trumpet

Till he shakes old hell’s foundations.

“Stop his ears”

And “dry bones” will click together out of the grave, an army of the dead.

And the living and the dead will be “caught up in the middle of the air” for the judging, for dividing the sheep from the goats.

And those washed in the blood of the Lamb will enter heaven “Singing new songs of Zion.”

And the others will go down to the bottomless pit.

And the wicked like lumps of lead will start to fall,

Headlong for seven days and nights they’ll fall,

Plumb into the big, black, red-hot mouth of hell,

Belching out fire and brimstone.

And their cries like howling, yelping dogs,

Will go up with the fire and smoke from hell,

But God will stop his ears.

“God will stop his ears.”

========

ONE FINAL NOTE: I have two paperback copies of God’s Trombones, one published by Viking Press in 1969 and one by Penguin Classics in 2008. The older one notes that the drawings in the book are by Aaron Douglas and the lettering of the chapter headings by C. B. Falls. The Penguin edition includes the drawings and lettering but gives no acknowledgement to Douglas and Falls. That’s not right.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.25.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.