The narrator of Leo Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat tells in the book’s opening pages of finding a “Tartar” thistle in a recently mown field — terribly tough, coarse and gaudily red and with “a stem prickly on all sides.” He is sorry that he picked it and then threw it away, “destroyed” it.

A little later, he finds a Tartar bush of three shoots:

One had been broken off, and the remainder of the branch stuck out like a cut-off arm. On each of the other two there was a flower. These flowers had once been red, but now they were black. One stem was broken and half of it hung down, with the dirty flower at the end; the other, though all covered with black dirt, still stuck up.

He could see that the bush had been run over by a mower and then raised back up, tilted, askew.

As if a piece of its flesh had been ripped away, its guts turned inside out, an arm torn off, an eye blinded. But it still stands and does not surrender to man, who has annihilated all its brothers around it.

“What energy!” I thought. “Man has conquered everything, destroyed millions of plants, but this one still does not surrender.”

“Like a mowed down thistle”

A “Tartar” thistle is the beginning and end of Hadji Murat, a fictional story of the historical figure Hadji Murad, an important Muslim Avar leader in the mid-nineteenth century battle of the people of Dagestan and Chechnya against Russian invaders.

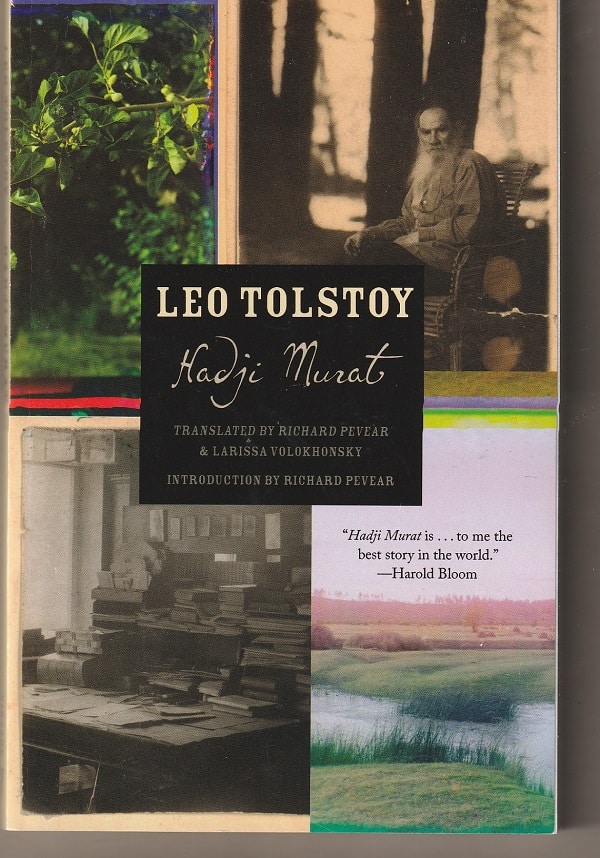

The short novel — 116 pages in the 2009 translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky — was Tolstoy’s final work. It was completed in 1904, six years before his death, and wasn’t published in full until 1917.

On the final page of the novel, Hadji Murat, caught in a firefight with militiamen serving the Russian troops, is struck by several bullets, falls, seemingly finished. But he struggles to his feet and attacks again.

He looked so terrible that the men running at him stopped. But he suddenly shuddered, staggered away from the tree, and, like a mowed down thistle, fell full length on his face and no longer moved.

“Like a mowed down thistle” — the fighter no longer moved but, for a time, he still felt as the militiamen struck and stabbed his defenseless body. And the narrator, in the book’s final sentence, says:

This was the death I was reminded of by the crushed thistle in the midst of the plowed field.

A dense and complex work

Brief as it is and without flourishes, Hadji Murat, which covers a few months at the end of 1851 and beginning of 1852, is a complex work, dense with action, character and themes.

It is possible to read it as an anti-war book, if only for the contrast between the often brutal violence of the book’s many battles and the beauty of a heedless nature in which that violence takes place.

For instance, after Hadji Murat’s death, the nightingales, “who had fallen silent during the shooting, again started trilling, first one close by and then others further off.”

“A vigorous feeling of the joy of life”

At an earlier point when the Russian troops, including a tall, handsome, untested officer named Butler, have destroyed a Muslim village for no purpose except an order from the Tsar, they return to camp singing happy songs.

There was no wind, the air was fresh, clean, and so transparent that the snowy mountains, which were some seventy miles away, seemed very close, and when the singers fell silent, the measured tramp of feet and clank of guns could be heard, as a background against which the songs started and stopped.

Butler, who later becomes a friend of Hadji Murat when the rebel is offering to switch to the Russian side, had entered the battle — the second of his life — “experiencing a vigorous feeling of the joy of life, and at the same time the danger of death, and the desire of activity, and the consciousness of belonging to an enormous whole governed by a single will.”

[I]t was a joy to him that they were about to be fired at, and that he not only would not duck his head as a cannonball flew over or pay attention to the whistle of bullets, but would carry his head high, as he had done already, and look about at his comrades and soldiers with a smile in his eyes, and start talking in the most indifferent voice about something irrelevant.

“Wailed without ceasing”

That neophyte’s joy at battle and the singing of the soldiers afterwards is contrasted in the next chapter with the scene in the village devastated by the Russian raid.

Sado, who recently had provided shelter overnight to Hadji Murat, had fled with most of his family to the mountains. When he came back to the village, he found his clay-plastered home destroyed — “the roof had fallen in, the door and posts of the little gallery were burned down, and the inside was befouled.”

His handsome little boy who had gazed rapturously at Hadji Murat was brought dead to the mosque.

He had been stabbed in the back with a bayonet. The fine-looking woman who had waited on Hadji Murat during his visit, now, in a smock torn in front, revealing her old, sagging breasts, and with her hair undone, stood over her son and clawed her face until it bled and wailed without ceasing.

Stabbed in the back.

“His eyes, always dull”

Hadji Murat can also be read as an anti-power novel inasmuch as the central character is a lively, forceful, attractive nitty-gritty personality who contrasts sharply with those in power — such as Butler, blissfully clueless about the rawness of war, and all the way up the ladder of power to the topmost spot of the Tsar, blissfully clueless about, basically, humanity.

Tolstoy devotes ten of his 116 pages to Tsar Nicholas I whom he depicts as vain, self-obsessed and heedless of how other people are affected by his decisions, such as his order for the series of attacks that included the one on the village that Butler took part in. For instance, here is the Tsar meeting one of his councilors:

His eyes, always dull, looked duller than usual; his compressed lips under the twirled mustaches, and his fat cheeks propped on his high collar, freshly shaven, with regular, sausage-shaped side-whiskers left on them, and his chin pressed into the collar, gave his face an expression of displeasure and even of wrath. The cause of his mood was fatigue.

And the cause of the fatigue was that he had been at a masked ball the night before, and, strolling as usual in his horse guards helmet with a bird on its head, among the public who either pressed towards him or timidly avoided his enormous and self-assured figure, had again met that mask who, at the last masked ball, having aroused his old man’s sensuality by her whiteness, beautiful build, and tender voice, had hidden from him, promising to meet him at the next ball.

Well, in fact, the Tsar did meet the young woman behind the mask and had her “taken to the usual place for Nicholas’s meeting with women.” So he was late to sleep.

“I just did”

But, even though it is an anti-war novel and an anti-power book, Hadji Murat is above all else an exquisite evocation of the vast range of humanity, from the stupid sterility of Nicholas to the craftiness or cunny or maliciousness of other characters, from Butler’s youthful romantic ideas of military glory to Hadji Murat himself, a man of violence and prayer and wit and curiosity.

Consider this scene near the novel’s end when Hadji Murat is still hoping to join the Russians to wage a blood feud against his former ally. He is taken to a military outpost where he meets Butler:

Hadji Murat’s relations with his new acquaintances were at once defined very clearly. From their first acquaintance Hadji Murat felt loathing and contempt for Ivan Marveevich and always treated him haughtily. To Marya Dmitrieva, who prepared and brought his food, he took a special liking. He liked her simplicity, and the special beauty of a nationality foreign to him, and the attraction she felt to him, which she transmitted to him unconsciously. He tried not to look at her, not to speak with her, but his eyes involuntarily turned to her and followed her movements.

With Butler he became friendly at once…

Later, when the outpost learns that Hadji Murat has been killed, some of the soldiers call him a great rogue.

“God grant us more such Russian rogues,” Marya Dmitrievna suddenly mixed in vexedly. “He lived a week with us; we saw nothing but good from him,” she said. “Courteous, wise, just.”

“How did you find all that out?”

“I just did….He’s a Tartar but he’s good.”

Patrick T. Reardon

1.16.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.