When Hawk was in the process of becoming a hawk, a man walked by and looked up into the tree and yelled, “What you need is to go get your-self a job…”

The memory of this comes back to Hawk and is, at first, amusing but then infuriating — “…the nerve of that character, and his lunch-bucket morality…to say anything!…”

Then, suddenly, far out in space, Hawk is no longer able to fly. With such snobbishness toward the earthbound, Hawk knows that a line has been crossed and that jim, the messenger and guide from God, is angry. So, Hawk says to jim: “All right. You win. If I have to love those bastards, I’ll love them. I’ll be as excellent as I have to be. I’m not going back.”

Hawk does not want to fall back to Earth. Hawk wants to get to the center of everything. But, by the end of Vivian Ayers’s book-length poem, after getting to the center of everything, Hawk does voluntarily, purposefully decide to go back specifically to help “those bastards.”

Incantatory language and a spiritual universe

Loving “those bastards” is an echo of the message of Christianity, but, in Hawk, Ayers is in no way toeing an organized-religion line. Indeed, in incantatory but also colloquial language, she has created a vividly described, multi-tiered spiritual universe of her own. In her inventiveness and her chutzpah to explain the meaning of life, Ayers brings to mind similar efforts by Dante in The Divine Comedy, and by William Blake in his “prophetic” poetry, and by the author of the Bible’s Book of Revelation with its seemingly endless cascade of startling and striking images.

Hawk is an allegorical narrative poem of personal struggle, fulfillment and responsibility set in the wilderness of space, written four years before human beings traveled into the vast emptiness beyond Earth’s atmosphere. An energetic work that moves with a jazz-like syncopation, it was originally published in 1957 in a hand-lettered edition that was distributed with its pages collated but held loose inside a cover, like a folio folder.

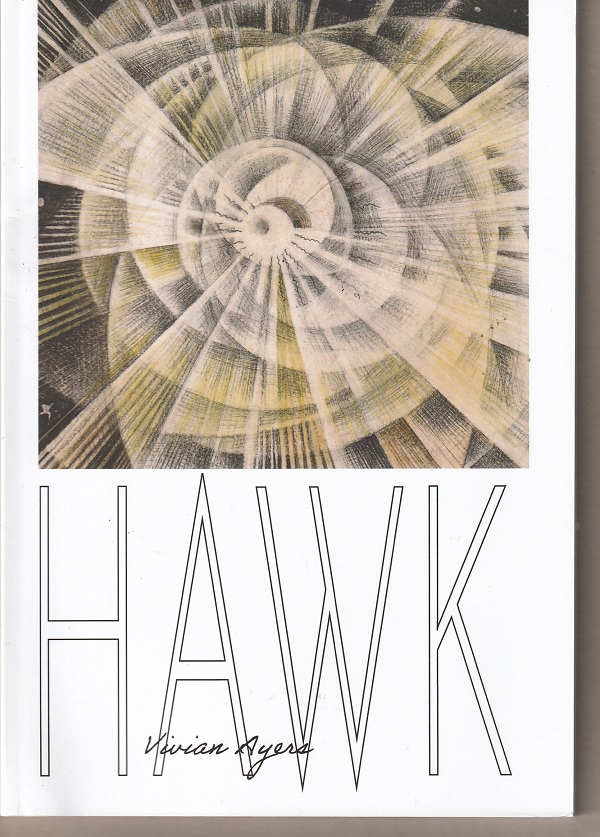

Now, it has been re-issued by Clemson University Press in two editions: a hardcover facsimile ($124.95) and a paperback in which the Kalem font has been used to suggest the original hand-printing, both regular and boldface, and the Adobe Handwriting font for the poem’s eight hand-written chapter headings ($19.95). Both editions feature the five exuberant illustrations by artist John Biggers used in the original publication.

God as “It”

As the poem opens, in the year 2052, Hawk, “operating from the level of Cestral mind,” is making a visit to Saturn for some wine-drinking with Gator, also called Red Eyes. “Cestral” is an example of several neologisms that Ayers weaves into her poem. It means something like “celestial,” but Ayers doesn’t use that word for two reasons: first, to put her own stamp on the alternative existence that she is envisioning, and, second, to give an echo of everyday conversational language with its frequent truncations.

Hawk, having been appointed “Guard of Sleep,” has stopped at Saturn while “enroute to Mars on an Hierarchical mission,” having to do with sobering up a reckless Martian. Hawk now is something of a divine messenger, like jim. The Divinity? Well, that’s an It.

“But the great one’s patience is a little longer than mine,” Hawk tells Gator. “It will pamper him. It hath much patience with the carnit mind.” (“Carnit” equals “incarnate.”)

“A Man on Earth”

In return for the wine from Gator, Hawk tells a story that begins, “Yes…but I have lived on earth. I was Man once…twice to be exact. And this show opens on Earth.” In another place, Hawk tells of having been “a Man on Earth.”

This is important because the tendency is for the reader to want to identify Hawk, the “I” of the poem, with Ayres, a tendency that is reinforced by one of the Biggers’ illustrations which shows Hawk, while making the transition from human being to hawk, with tiny breasts. (Biggers saw Hawk as Ayers, according to the poet’s daughter Phylicia Rashad.) Although Hawk makes some barbed comments about the relationship of men and women, this is not a feminist poem, neither is it a poem about the experience of African Americans.

By writing that Hawk had been “Man” and “a Man on Earth,” Ayers is asserting that hers is a poem that addresses the situation of all humanity — indeed, the meaning of life. This was an era when the word “man” was still used to refer to all people, as in such terms as “the family of man” and “mankind.”

Hawk is an Everyman, a representative of everyone human. And, like Christian in the morality allegory A Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan, like Dante in the Divine Comedy, Hawk is on a journey to the Godhead.

Unlike Christian and Dante, however, Hawk holds no truck with institutional faith, saying, “Christianity/is still/the dull/and pretentious lady—/Til now, I am not impressed with the aim of priests and Clergy, whose aim is — at best — a seething thing.” (This is an example of the way Ayers knits together phrases in regular type and boldface throughout her poem.)

“A bird life apprenticeship”

And, as a Man on Earth, the future Hawk finds much to reject in the way people live their lives:

“The unsane so far outnumbered the sane that even Tolerance got over on their side. Even Tolerance. Sane ones, not being able to take it, quibbled off their quids, were locked up, labeled insane and given treatment…the unsane working on the insane — umph!

“The most amusing were the ‘authorities.’ Little folks compelling little folks to revere their squalid opinions, find reward in their paltry emanations, and even fear them.”

Finally, this Man on Earth has a solution: “a bird life apprenticeship!” So, climbing an elm, the Man on Earth perches on a limb most of the day, going down before sunrise to scratch for worms, ridiculous to both people and birds. But on the forty-ninth day — “[O]n waking further and glancing down, I could see that my feet had webbed…my toes were webbed…prim and clinching!…And I raised my arms to make an expression of thanks…but there were no arms! High on the thorax there were little white wings!”

Now, Hawk hopped from branch to branch, whistling happy tunes: “I could fly. I was free! Earth would be lost moss off a cannon ball—” And Hawk thought: “Thank god…thank god…there is a sky…”

Akin to Blake and the Book of Revelations

Hawk’s journey, however, is just starting. Rising level by level, up above the Earth’s surface, and up into the far reaches of space, and farther still, Hawk is learning at each stage lessons that are needed to continue rising such as:

“Positive means you recognized the power there is; and negative means you don’t recognize It. To the extent you recognize It, It recognizes you.”

There is a rhythm and cadence to Hawk’s rising flight, even when progress halts or seems to fade. Ayers’s poetry is predominately in the form of prose paragraphs although phrases and sections in lines also appear, often as songs.

Another element of sound and sight is the frequent appearance of boldface words and phrases that add emphasis, like a melody raised another octave as well as Ayers’s frequent use of dashes and ellipses.

The effect is hypnotic, incantatory, akin to reading one of Blake’s prophesies or a page from Revelations. The reader can’t be sure how all the ideas fit together, but they are expressed with great verve and commitment. Here, for instance, is a Revelations-like scene:

“There was a knelling tone like a call for true reckoning…as if the Sun sat beckoning all things before its judgement…It was like some dream out of early youth to witness authentic ember — the author of autumn sunsets, cathedral bells…the glow about camp fires in the night. I thought to call it a thousand other eyes…but when I would have uttered words of it, my jaws set fixed, and I mumbled half word and witlessly through stunned lips…”

And, finally, Hawk comes face to face with God, “and the man within me died, faintly gasping, ‘…my god, this is God…’ ”

Return to Earth

Unlike The Divine Comedy and Pilgrim’s Progress, Hawk’s journey doesn’t end there. Unlike Dante and Christian, Hawk, feeling “a growing compassion for Man,” decides to go back to Earth.

“I propped my wings like oars and backed out of the area as fast as I could. I had to get back!…I would show mankind the way.”

It is a difficult return, a difficult “regression.” Hawk tells Gator that few believed the story of flying in space, and Hawk was met “with much disregard, neglect and abuse, and disbelief, and it’s painful.//If he’s not very careful he gets more hard knocks than anybody…because the least he can accept is the most Earth offers…goodness, beauty, truth — and dignity —”

Hawk, the book-length poem Vivian Ayers wrote more than sixty years ago, is a literary jewel that has been unearthed from the obscurity of the past and made available to readers who, like the poet, are searchers, riskers and dreamers.

The music of Hawk is complex, enthralling, exhilarating and astonishing. The poem-book is as vibrant and inspiring today as it was in the middle of a much different era. Its story of striving, discipline, steadfastness and compassion is universal and timely in any age.

The Making of “Hawk”

The photo on the back cover of Hawk by Vivian Ayers shows the author as a young African American woman in her early thirties, sporting a long-stem pipe in her teeth and wearing suspenders over a light color shirt. This was not how most mothers of three dressed in America of 1957.

“That was a purposeful statement,” her daughter Phylicia Rashad, the actress and director, recalled in a recent Zoom interview.

Ayers, who, that year, had published Hawk, her book-length poem echoing Dante and William Blake and the ecstatic experiences of the saints, gazes just a bit to the left of the camera with thoughtful, self-possessed eyes. The image captures her mother’s free spirit, Rashad said, and she told this story about midcentury Southern culture:

“My father was a dentist. You understand the societal structure and how a dentist’s wife is to present herself, all of which she did very well because she grew up in the South and she knew what to do. It’s fine.

“But now she was onto something else. The ladies, they had their little club, and what Mommy wanted to do is have what people have now, book clubs. She wanted to introduce poetry and literature and read it and talk about it and share ideas. But she said they wanted to sit around and talk about their hysterectomies. And she couldn’t do it! She had to leave.”

“Collating pages”

Born in Chester, South Carolina, in 1923, Ayers lived in Washington, D.C., married Arthur Allen in New York City and moved to Houston where she gave birth to her three children, all of whom found careers in the arts. Rashad, among many credits, is best known for her role as Clair Huxtable on The Cosby Show. Her younger sister, Debbie Allen, is an actress, dancer, choreographer, singer and director, who starred on the television series Fame. Their older brother, Andrew “Tex” Allen Jr., is a jazz trumpeter.

After Ayers and her husband divorced in 1954, she spent the rest of her life promoting and organizing cultural programing, Rashad said. For a time, she organized events at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, as well as in and around Houston. In 1971, she began publishing a literary magazine The Adept Quarterly and borrowed that name for her Adept American Folk Gallery where, according to the New York Times, “Black cowboys, black artists and figures from Texas history — including black astronauts of NASA — mingled.” Later, she reestablished the gallery in Mount Vernon, N.Y.

Rashad was eight years old when her mother published Hawk, and she helped make it happen:

“I remember collating pages into the night. The way the pages were, they were not bound. They were collated and in a cover that held them. The pages were loose, but they were organized. I remember we were there for hours doing it, and I remember the sun coming up. We were having fun, though. We turned it into a little game and a party.”

“What the focus has to be”

Ayers had published a more traditional poetry collection Spice of Dawns with Exposition Press in 1953. Later, she wrote a play Bow Boly that, Rashad said, was “about an angel who has come to earth and gets entangled in it, comes to earth with an intention, with a cause, with a mission, but gets entangled in it, engrossed in it. We performed excerpts of it at Texas Southern University — I was 13 years old — in 1961.”

As an eight-year-old, Rashad said, she didn’t read Hawk.

“But I understood it through the artwork — and through understanding my mother, too. I would not understand the profundity of it, I would not understand the uniqueness of it for a little while.”

Now, as an adult, she said,

“I marvel at it. I marvel at the cadence. I marvel at the imagery. I understand what she is saying when she’s talking about flying above gales of wind and what the focus has to be. She’s talking about many things, and one of the things is the art of writing and giving oneself to that discipline where perfection is being asked of you. But it applies to everything that human beings do — whether it’s teaching, whether it’s writing, whether it’s research, whether it’s childcare, whether it’s community planning, community action or involvement, seeking that level of perfection and surrendering to love, unconditional love.”

“Inner experience”

Ayers, who turned 100 in July, 2023, recounted to her daughter once a moment in the writing of Hawk. “When she is describing what she sees, she saw that. It’s inner experience,” Rashad said. “She told me that she was hanging Debbie’s diapers on the line when the sky, it was as if the sky opened and she could see. She dropped everything and ran into the kitchen where her typewriter was to write it as she had experienced it.”

Ayers had read Dante’s Divine Comedy and Virgil’s Aeneid before writing Hawk, but only later did she study William Blake in a deep way. “She was of that ilk,” Rashad said. “She wasn’t copying them. She liked them because they resonated with her and her own thinking.”

“Direct her own course”

Like the central character in Hawk, Ayers carved her own path through life, and it was a journey, Rashad said, that began when she was a young girl and her mother died of tuberculosis.

“As she sat in her mother’s funeral — this is what she told me — and listened to the things the adults were saying, because you know how people can carry on at a funeral, she decided that there were none of them intelligent enough to tell her anything. She was not going to let them tell her what to do. She’s nine years old. She decided they would never be able to tell her what to do. She would direct her own course. Nine years old, imagine.”

And it was a spirit that Ayers passed on to her children.

“It’s caused some hiccups and some problems,” Rashad acknowledged, “but, oh, the joy of it all.”

Patrick T. Reardon

7.9.24

A much different version of this review was published by Another Chicago Magazine on 6.25.24.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

I can’t wait to get my copy! Thanks, Ayer’s and Allen for

having the Hawk published,

Is there any way I can download

The book on my IPad ?

I’m sorry, Jearline, but there isn’t a digital version of this book. https://libraries.clemson.edu/press/books/hawk/

Pat